material evidenceof its whole spiritual life. The realistic Serbian literature at the turn of 19th c. documented the Bulgarian character of the population along Morava and Nišava.

The abovementioned lands which Serbs (whom the local Bulgarian population dubbed "Šumadians") considered as their newly liberated

regions in 1877-78 and proclaimed as part of Old Serbia

immediately striked Šumadians with their foreign exotic southern nature

and the specificity of their population and they hastily started their assimilatory activities because Niš, Leskovac, Vranja, Prokuplje and Kuršumlija were at the gates of Macedonia and North Albania.

Before occupation of these lands, Serbs didn't hide that people who lived there were Bugari because the attention was concentrated on Austrian lands. But once settled in this Bulgarian region, at once, as by magic, the latter became a part of Serbia

and the population turned out to be Serbs, speaking in some peculiar eastern Serbian dialect

with archaic Serbian forms

.

The Bulgarian Principality before its liberation was powerless to react against the separation and estrangement of these lands from the heart of Bulgaria.

But could Serbs in 5 decades, after all their efforts, obliterate the language, customs and morals of those whose ancestors in 1850s started the church struggle as a first step towards national liberation with a stubbornness possessed only by Bulgarians; could they assimilate those whose fathers rebelled in 1883 in the famous Zajčar rebellion spread over the whole Timok region and ready to break forth in the Morava region – a rebellion that reflected the spontaneous opposing feeling of the Bulgarian whose dream about San-Stefano Bulgaria did not come true?

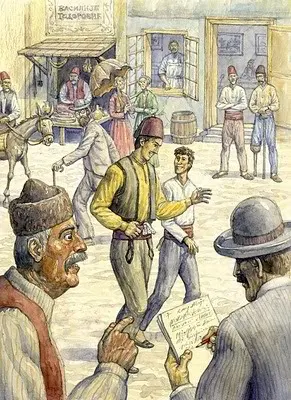

Serbian literature answers this question. The realistic Serbian writers describe the life of Morava Bulgarians with well preserved Bulgarian types, Bulgarian morals, language, songs, proverbs, environment – the agitations and expressions of the Bulgarian national temperament.

Borisav Stanković: the poet of Vranja

Borisav Stanković (1876 – 1927) was born in the town of Vranja. The language of his native town left live and intact Bulgarian traces in his writing for which he was reproached by Serbian critics. And yet the talented Vranjanin got his way with his language. According to the Serbian critic and esthete Skerlić

Borisav Stanković takes the first place among the modern Serbian writers. ... Before Borisav Stanković Serbian literature was limited to the northern and western Serbian regions. Stanković first introduced in the literature the southeastern Serbian lands, that part of Old Serbia [?] which Serbia liberated [!] in 1877-1878. He is a bard of that new picturesque and interesting exotic world, of his birthplace Vranja where he spent his childhood, that left the strongest and unforgettable memories and from which, in his stories, he cannot be set free. He does not sing about the present Vranja which is modernised [and Serbianised?] but about Vranja of theold days, the patriarchal people, with their narrow views but cordial life. He describes what he saw and felt, he usually describes people who really existed and events that really happened. ... There is in his description of Vranja life something very much Vranjanian, local, interesting archaic Serbian dialect [?]. Moreover, in all this realistic description of one of the Serbian nooks where many archaic and patriarchal elements are still preserved, there is also something very personal, impressionistic, lyrical ... In all his stories in which a struggle is going on between East and West, between the personality and the masses, passion and moral, dream and reality, poetry and prose of life, in all these things to which he could give magnitude and verse, Stanković always participated with all his open soul.

Old days

And indeed, leaf through his uniquely affectionate Stari dani (Old days) and you will discover the whole soul of our Vranjanin who loves his local Bulgarian language despite the reproaches of Skerlić that his syntax was faltering and the general literacy unsatisfactory

Skerlić, p. 469. Moreover, in his short stories you will discover such visions and pictures, such descriptions of old Vranja with its streets and high fences, large porches, yards with motley maiden gardens; so many dear memories about St. George's Day, about vintage time, etc., etc., that carry you to the memories of your own childhood and make you feel the beauty and breathe the air of the Bulgarian Vranja.

Let's briefly quote a little from Stari dani to show the reader the nature of that Stanković language in which indeed the Serbian syntax is quite faltering and which as a whole is unsatisfactory

. These flaws

are exactly what makes his narrative living and realistic:

Па кад е истина, што долазиш? Што ме не оставиш ... Ето, имаш жену, децу ... – Ех, не спомени ми. – Да, ти имаш, а jа? Па jош и то, да нешто он чуе, онда где чу jа, где? (p. 14)

– А што? Ти ли си ми дала ...

Пукне ли лето

... (p. 49)

Снашка Паса ... пева стару песму: како кадън Стана у башту ишетала, изгубила сърма-колан, у сречу joj млад калуђер, нега набедила за колан и куне га:

Ако си зел срма-колан

Като колан да се виеш

The monk answers:

Не сам, Стано, жива била!

(p. 84)

Ако сам зел сърма-колан,

Като колан да се виjем

Око твоjа снага ...

Another song:

Што си, Лено, на големо

(p. 64)

Барем да си од колено?

– Ако не сам од колено

А jа имам црне очи

Црне очи, медна уста.

– Па да се ожениш. А да знаш какво сам ти девоjче избрала

(p. 85)

Our Christmas

The town of Vranja is on the road to Macedonia. Listening to the speech of the native population you could hear a very perceptible Bulgarian tonality of that dialect spoken in Macedonia.

Open Naš Božić (Our Christmas) and read about the Vranja Christmas which is very different from that Christmas which is celebrated in Šumadija.

The children impatiently await Christmas.

Море каков сан? – Неделя ево како се не спава. Те Божич дошао до Скопља, сад jе у Прешево, па у Биљачи, и све ближе, ближе ко нама

...

The Vranja Christmas comes along the same road on which the grandfathers, expelled by the Turkish rule from Skopje and Central Macedonia, came to Vranja and settled here. The children enjoy their new shoes with buttons

. The mother, sleeves folded up to her elbows, the whole week tidies up, washes, beats the carpets, puts things in order. The bowls shine on the shelf. The table and the baking dishes are sheltered near the wall. The veranda is plastered with red clay and the window panes of the low father's house shine solemnly.

Christmas has already come. Pious people come back from church. Joy and satisfaction fill every house. Gypsy clarinets scream through the neighbourhood.

Sweetly sad memories.

The narrator, then just a small boy, comes back from church under his father's roof. The mother sits on the couch and broods. Tears fill her eyes. Ever since she was widowed, the holiday joys cannot be felt in this home. But suddenly she sees through the window Иван Паламарът (Bulgarian definite article), a friend of the late host, approaching to bring a little joy to the silent house. He brings along the Gypsies.

This house, too, bursts with exultation. The clarinet shrieks, the tambourine starts madly beating and the sprightly Fatimè with the wide shalwars begins belly-dancing, cracking her henna-covered fingers, and singing with a female Gypsy alto:

Jа не жалим снагата моjа,

Jа не жалим снагата моjа,

Жалим сърмали jелек ...

And the mother, tears slowly dropping down her face, looks tenderly at her son as if to tell him:

– Божић, сине. Видеш ли?

(In Serbian should be: jе л'си видео).

Koštana

One of the good works of Borisav Stanković is his Koštana – a short novel which he subsequently re-worked in a play (Dramska priča published in 1905 in Serbian Karlovci)

To cut it brief, we won't go into the short novel Koštana, which abounds with many Bulgarian linguistic forms from the region of Vranja, but we'll take up his dramatised work in which the writer strived – according to Skerlić's recipy – to correct his syntax and spelling

. Unfortunately, however, Stanković again remains incorrigible Bulgarian because he still uses many Vranjanian local

words and idioms such as уста да имаш, а език да немаш

, ти си крива

(p. 8), голема гора

(in Serbian велика шума

, p. 18), etc. In order to be well understood by his readers in Šumadija, the author was compelled to make something like a dictionary in the footers of pages 19, 20, 22, 38, and others where he gives a translation of the Vranjanian words:

батка – старjи брат

жал – бол, саучашће

лош – рђав

хубав – леп, мио, млад

черпня – зељани суд

бробиняк – мрав, etc.

The play Koštana presents the life of the poetic Vranja Region with its Vranjanian Carmen

– a seductive young Gypsy named Koštana who disturbs the men of the whole town with her grace and dancing.

Stojan, the son of Hadji Toma, is hopelessly in love with the enchantress. His father is very angry about that. He insists that the mayor Arso take measures against the seductress by deporting her to Turkey or forcing her to marry to any Gypsy so that she settle down and the families in town live in peace. Hadji Toma is very worried about his son who runs after the Gypsies and dresses and feeds the white world

.

– Ето ти твоjа Србиjа, – he speaks with indignation to the mayor of Vranja. This is it, Serbia, to whom bai Arso serves so zealously and to whom Vranjanins cannot easily reconcile.

But the mayor's brother Mitko is also in love with Koštana. He deserts his wife and children and is mad about her. In one scene Hadji Toma finds his son enjoying his time with friends, Koštana, and Gypsy clarinets far from the town, at the mill. Hadji Toma falls infuriated on his son and chases him away.

But ... those beautiful Gypsy eyes, that luxuriant hair, body, and gait little by little awake and excite his blood. So he takes the place of his son and continues the revelry. He even leads all, with the Gypsy clarinets and tambourines into the town and in his home.

The play is studded with many Bulgarian songs from Western Bulgaria and Macedonia. Thus, on p. 17:

Jа не жалим снагата моjа, џанум!

Jа не жалим снагата,

Жалим сърмали jелек, etc.

On p. 23:

Шта си, Лено, на големо

Барем да си од колено, etc.

(a popular song from Veles, Macedonia)

On p. 29:

Отвори ми бела Ленче

вратънца, вратънца,

Да ти видим, бело Ленче,

устънца, устънца.

– Не могу ти, пиле Миле,

да станем, да станем,

Маjка ми jе села, Миле

на фустан, на фустан.

On p. 30:

Стоjане, море, Стоjане,

Не ли смо пуста родбина,

Где се jе чуло, разбрало

Брат сестру, море да зема.

– Стамено, море, Стамено,

Стамено, китко пролетна,

Не си ли чула, разбрала:

Широко поле ход нема,

Дубока вода брод нема,

Ситно камене броj нема,

Убава мома, мори, род нема.

On p. 32:

– Стани, Ванке, постани,

Да ти зборам два збора;

Да ти зборам два збора,

Дори да те изгорам,

Дори да те изгорам,

За тоj твоje пръстенче;

За тоj твоje пръстенче,

С'с дванаест камена.

On p. 35:

Еj, ако те jе, пиле, мала моме,

Жал за мене,

Стани рано, пиле, мала моме,

Испрати ме

Море, испрати ме, пиле, мала моме,

Накраj село

Еj, накраj село, пиле, мала моме,

У ливаде ...

On p. 43:

Да знаеш, моме мори, да знаеш,

Каква jе жалба за младост,

На порти би ме чекала,

Од коња би ме скинала,

У собу би ме унела ...

Оф, аман-заман, младо девоjче,

Изгоре ми срце за тебе.

On p. 54:

Механџи, море, механџи,

Донеси вино, ракиjу,

Да пиjем, да се опиjем

Дертови да си разбиjем.

As we can see, the spelling

of some songs is corrected here and there, for example:

Що си Лено на големо

became шта си

; не ли сме пуста родбина

became не ли смо

; Със дванаест камена

became с'с дванаест

; Донеси вино, ракия

became Донеси вино, ракиjу

. The song

Море насред село шарена чешма

течеше, аго, течеше,

Море на чешмата до две до три моми

стоеха, аго, стоеха.

which is sung all over Macedonia, in Dramska priča Koštana is corrected syntactically

thus:

Море насред села шарена чешма

течеше, аго, течеше,

Море и на чешму дво до три моме

стоjашев, аго, стоjашев.

And yet, all meticulous spelling and syntactic corrections

failed to Serbianise the folk poetry of Vranja because its very existence is the transfer of rhythmic linguistic forms from mouth to mouth and from generation to generation. Indeed, one can guess the origin of the above quoted songs not only from their language but also from the voicing and the subject.

Thus, a Serb will never use definite article: снага – снагата (body – the body); and only снага without article in Serbian means force

and not body

; therefore, unlike чешмата, the syntactic correction

spared снагата because Serbs would be confused. There is no idiom що си на големо in Serbian; apostrophe is put instead of every middle ъ in Bulgarian words: джан'м, с'с, etc.; Serbs do not use the words and phrases: разбирам, зборувам, пиле, испрати ме, да знаеш, за тебе, каква е жалба за младост, etc.

Stevan Sremac: the poet of Niš

Stevan Sremac was born in 1855 in the town of Senti in the former Austrian province Bačka that was later incorporated in Yugoslavia. Only 13-years old he came to Belgrade where he graduated at high school and then at the Historical and Philological Department of the Belgrade University in 1878. After that Sremac was a teacher in Niš for a long time. It is very important here that Sremac, as a philologist, took seriously the linguistic aspect of his novels and novellettes of country life which he renders in such difficult Niš dialect

that the Šumadians must use a special dictionary to understand it.

The Serbian criticist Skerlić, noting that Sremac began his writing activity in his mature years (as late as 1890), described him as Niš poet who gave all his sympathy to the newly-liberated regions that preserved the old-time patriarchal life

. In Niš, Sremac spent dozens of his best and brightest years of his life. There, he started to write, as a photo

of Niš life, his Ivkova slava, Zona Zamfirova, Uncle Jurdan, Eksik-Adji, etc.

Stevan Sremac, a romantic in his soul, negligent to the cold and heartless [Serbian] West – as he stated himself – found in Niš immediately after the liberation a picturesque, exotic East where the old life, the old ideas conserved their influence. He felt very well among this eastern decorum and among the simple, cordialpeople of the old mouldfor whom life does not bear problems but only joy. He felt the poetry of old Niš and began to praise the mercurial living of the old and cheerful Nišlii. And he did this in an entertaining and picturesque manner, warmly and pleasantly, with many local colours, and often in the characteristic Niš dialect Skerlić, p. 400

Additionally, Skerlić considers Sremac a relist in the style of his writing

who looks at life with attentive eye and who always writes in his notebook characteristic words, jokes, gestures, situations, expressions, songs, etc.

that gave to his compositions a saturated local colour and complete realism. That's why the Niš life looks original and interesting and becomes a new world in the Serbian literatureSkerlić, pp. 401-402

The extent to which Stevan Sremac and Borisav Stanković are photographers of reality (let's not overlook this aspect of Serbian creative art) is shown by the fact that they described real events not hiding the names of their prototypes. Thus, bai Ivko of Ivkova slava is a real person. When the dramatised novel Ivkova slava was performed in Niš, bai Ivko stood up among the audience and approved or protested about some exaggerations or distortions. Also, Zona Zamfirova and her father – an old Niš chorbadjia – are well-known in the whole environs of the town.

Borisav Stanković's Koštana is also known in the whole environs of Vranja. When the play Koštana was first performed in Vranja, Hadji Toma was taken along to the theatre by his son and without a warning he saw on the stage another Hadji Toma disguised to an amazing likeness and was embarrassed. But his embarrassment passed all limits when he saw on the stage all his family and very clearly recognised his friends and Koštana. Extremely confused, he left the theatre cursing. Koštana, so seductive when young, lived to be old woman and died in the usual Gypsy misery.

One of the Stanković's aunts held a grudge with her imprudent nephew for a long time because he indulged in disgracing her in his books.

All this comes to show how precise and scrupulous were Borisav Stanković and Stevan Sremac as country life writers whose work gives us valuable and irrefutable linguistic materials.

Ivkova slava

The Serbian slava is an ancient family holiday. It is the day when the forefather on masculine line adopted Christianity (several centuries ago) and was baptised. This day is observed and passed on from father to son as the most stringent tradition.

On the day of slava a round loaf in the shape of crown is put on the table with a tallow candle burning in front of it all through the day. In the evening, the host can extinguish the candle by dipping it into wine; if the host is not alive or is absent then the eldest son or grandson can extinguish the candle even if he is as young as 2 years. Guests come during the day and they are treated up to 3 times. Boiled meat is also served to the guests. Grain is not served on the days of St. Arachangel and St. Ilia because these saints are still alive. Since most baptisms happened in old time on the days of St. Nicholas, St. Arachangel, and St. George, these are the days with the most slavas.

In Šumadija slava was preserved in its original form: in its eve the son or the grandson of the home where slava will be celebrated visits all friends and relatives and invites them to the slava lunch or supper by offering them a keg with boiled brandy and honey. Only invited guests can come to the table. Eating and drinking has no end – till morning, even several days after. In Morava region, this Serbian custom is newer and not completely adopted.

The slava is stringently observed and honoured as a family holiday. No one dares to change the day of the forefather's holiday except daughters who adopt the slava of their husbands. Even in the poorest home, no one economizes on eating and drinking in the slava day.

Such family holidays, but in a very different form, are still observed in some parts of Bulgaria (kurban) especially in Macedonia where they are called sluzhba. Somewhat similar to slava is the widespread Bulgarian custom Name Day which is celebrated on the day of the saint with the same name as that of the celebrating person.

Serbs insist very much on their slava which in modern time they raised as their national cult and loudly proclaim that: Where slava is celebrated, all is Serbian

.

Let's note here that in the newly-liberated regions

such as Vranja, Leskovac and others, slava has not substituted the Name Day.

So, bai Ivko of Niš celebrates slava ... And what kind of slava is Ivko's slava, how quickly was it imposed on the people from the newly liberated Eastern region

, Sremac will tell us because as a conscientious photographer

and Niš poet he could not hide this.

Several days before St. George's Day feverish preparations for slava are going on in the home of Ivko Jorganjiata (the duvet-maker; note that his name is Ivko, coming from Ivan, and not Jovko that comes from Jovan). The apprentices dare not step on the newly clayed veranda and carefully make wide steps.

The holiday comes. Mariola, the neighbours' girl, serves the guests. Since morning different guests come in and out – craftsmen, clerks, tradesmen, with wives, with children, relatives, acquaintances, strangers.

Various conversations are started. It is very evident that the slava in this newly-liberated region

is new phenomenon. Ivko Jorgandjiata, once again talks about his trouble

as he has done on each slava; how his grandfather abandoned the old slava and chose a new saint. Of course, the ancient family tradition doesn't allow such change of the slava day that has been transferred from generation to generation for ten centuries. The problem is that bai Ivko lies to himself and to the guests that the change was done by his grandfather because his relatives probably know that his parents and himself celebrated their Name Days.

Old Nišlii (just as Timočani), if asked, will tell you that once по старински се е служба служила, а съг – по-новому, се слава слави.

As soon as Serbs became masters of these eastern Bulgarian lands they undertook, together with the repressions and propaganda, to obliterate all ethnic symbols that could show the Bulgarian character of the population in these newly-liberated regions

. This course of quick assimilation was especially accelerated after the Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885. Thus, the white woolen peasant dresses in Niš Region were substituted compulsorily with black dresses, in Šumadian cut. For this purpose, Serbian tailors were sent to villages, and the travellas ** of women in Timok Region were forbidden in 1886 with a special decree of King Milan. Together with the elimination of these Bulgarian symbols, everywhere in the newly-liberated regions

a massive agitation was carried out for the Serb-characterizing slava. Each time when a dispute about the language of Nišlii and Timočani breaks, Serbs dash out and try to dismiss all arguments with the rejoinder: Yes, true, but they celebrate slava!

But not only the Bugarashi

celebrated such slava: among Ivko's guests stands out the figure of Mr. Dr. Milan Ružić, Jew by ethnicity (Sremac mentions on p. 20 that previously he was called Moritz Rozenzweig); his Honour Milan Ružić also adopted the Serbian slava because he had to keep his social status and he had willy-nilly become a true Serb

.

– Which slava do you celebrate? – one of the women guests asks him.

– I and my Missis celebrate the Third Day of Pentecost. (p. 30)

Some guests already want to leave. Bai Ivko tries to make them stay:

– Што! Ама зар саг и ти господин доктуре? Ето такоj си е таj! Штом (щом not ћим) се jедан дигне (not диже) и иска да си отиде (Skerlić caught a typical Bulgarian phrase), виде и ониjа, па други. (p. 22)

And the hostess adds:

– Па елате jутре барем на патерицу.

As the Niš language requires a special dictionary to be used by Serbs, so Nišlii need a dictionary for the Serbian words:

– Патерица се вика (not виче) женски светак ... (p. 23)

As just said, Šumadians and the newly liberated

do not completely understand each other. Thus, the host offers танир са дуваном и цигар-папиром

and invites everyone:

– Коj пиjе тутун нек се послужи. (In Serbian: Ко пиjе дувана).

They fold cigarettes. Silence. Ivko asks one of the guests:

– А ти, господин Марко, ћуриш ли?

– Како рече? (doesn't understand the Bulgarian word)

– Викам: ти зер не пушиш? Па саг ич ли не пиjеш тутун ... (p. 32).

At another place Kalcho explains:

– Па знаш, господине, како ће да ти речем ... од време си научих па што да правим! ударим на Лоjзе па отутке се спуснем с пушку теке, ради адета ...

– Are the environs rich, is there game? – asks the treasurer.

– Па има ... Има време за заjаци, има срндаки, има за шотки, што ги виjа, из Шумадиjу што сте, викате патке дивjе, а ми ги па викамо шотчичи ... (it should be the other way round and that's why it provokes laughter).

It turns out that among Ivko's guests there is a Šumadian idler, Svetislav, unknown to anybody. He has settled uninvited in Ivko's house and feasts just as all Serbs who settled uninvited in this Bulgarian region. At the end of the novel Svetislav succeeds in marrying the neighbours' girl Mariola who presently serves the guests. When the bridegroom (a former tramp actor) begins to strut in front of his young wife, she turns to him with astonishment and even with despair:

– Море, дизаj се, фантазиjо, ич не те разбирам што збориш! (in Serbian: баш не те разумем шта причаш). О, Божьке, збори си като мутафчиjе (p. 199).

Yes, these are indeed two worlds that do not understand each other, this is a real struggle between East and West – as Skerlić says – between the small Bulgarian East and the Serbian West, between the the person that came from outside and the mass, between the dream of the newly-liberated and the ugly reality which the Serbian regime imposes ...

Bai Ivko has good friends in the persons of the Wolf, Kalcho, and the Grass-snake, esnaf people

(middle-class people) with whom he is very close and intimate. In the evening, after the guests have left, the three good Ivko's friends stay behind to have some more eating and drinking. They want to have a big feast as at a true slava; moreover, as friends of Ivko, according to very favourable to them regulations for this holiday, they are to be at the most prominent place at the table. However, bai Ivko still supports the Name Day concept and as we'll see later on, he opposes the Šumadian slava which he adopted only by name. He leaves his guests and goes to bed. His friends, however, among whom is the total stranger Svetislav, the tramp actor, themselves pour wine, bake appetizers and continue the slava ...

In vain is Ivko's anger, in vain he chases them away because they are going to ruin him. Our newly Serbianised Nišlii – the Wolf, Kalcho, and the Grass-snake, won't listen to reason. They feast and sing through the night. Ivko wakes at some time and listens to the clamour.

– Па още ли са тия тук? – he remonstrates. (In Serbian: Па jош увек ли су овe овде?)

But the slava does not allow the host to leave his best friends with whom he has lived како сол и леб

(p. 51) and go to bed. This is not a Name Day on which the guests are received and sent off during the day and the neighbourhood rests peaceful until evening. Our culture-bearers Kalcho, the Grass-snake, and the Wolf don't give a penny about the neighbours' opinion. Drinking and singing go on until dawn. Such lumpuvane

(romping) which is usual for Serbs, is something out of the way for the peaceful esnaf habits of Bulgarian Niš. The description of the town atmosphere reminds us the Bulgarian provincial towns at the time of the Ottoman rule:

The neighbours get up. One can hear the pattering of pattens in the adjacent yards. A nappy shalwar-clad woman runs out, washes her white face at the well and, face still unwiped, peeks through the plank fence to see where this uproar is coming from ... People pass on the street. Girls run to the tap, baker boys pass with bagels and pinirlii (cheese-buns) and shout at the top of their lungs ... lapse into silence for a while to listen and then laugh aloud and go on their way.

Isn't there somewhat unusual and strange in this rumpus for the Niš esnaf people

indeed!

The slava in Ivko's house continues through the second day. The Wolf and Kalcho chase the fowls in the yard with the duck gun, slaughter, pluck, cook; get hold of a lamb, skin it in a hurry and roast it. Ivko, jumping out of his skin, goes to complain directly to the mayor.

– Господин преседниче, што направише сас мен (not шта учину са мном) и моjу кућу? (p. 113). Па данас трећи дан, маjка му стара! (p. 114). Е па не сам си ни ja битолско магаре (not магарац), па да потеглим толки товар! (p. 114).

The dialogue with the mayor occupies 20 pages.

– Па викам да скочиш, господин преседниче, та да видиш сас твоjе очи моjу бруку и моjу жалос. Ене ги там седе, па на сваки черек сата по jедно ручање (p. 114).

– Оно е едење, оно е пиjење, оно е пуцање, че видиш и чуjеш и па нече да веруjеш. У зем да пропаднем оди срам, што че рекну па комшиjе. (p. 115).

Of course, the mayor puts on his hat and goes himself to see the scandal

and to pacify the roisterers who want to ruin Ivko. The mayor is a Šumadian who came to the exotic newly-liberated region

to have a good time. Ivko's expectations and hopes to see law and order are useless: the mayor gets ahead of Ivko and goes to Kalcho, the Wolf, the Grass-snake, and Svetislav. He finds them slaughtering two more lambs.

– What on the world these people do! They cut meat. Just look at them! They can't cut the steaks in the right way ... Come, give this knife to me. So. This is how you cut steaks, see? What? You don't have enough wine, do you? O.K. ...

So the slava continues purely in the Šumadian way. Only Gypsies are lacking. They send for them.

On coming home, Ivko hears the Gypsy music from afar and puts his hands to his head.

– Леле маjке, што ће баш да пропаднем! ... (p. 150).

The Šumadian mayor convinces the Wolf that today is his slava, too. Since the slava cult is not yet established in this region, the Wolf readily agrees that his slava is exactly this day. Sremac unnoticeably puts in the manner in which Šumadians suggests the slava to Moravans who manifest spontaneous opposition in the person of Ivko Jorganjiata and the unaccustomed neighbours. So, the Wolf starts celebrating his slava.

Of course, Kalcho, the Wolf, and the Grass-snake have the profiteering kelepir mentality of the ubiquitous Bulgarian bai Ganyo and they begin the new slava again in Ivko's house and on Ivko's account.

So, presently it is the family slava of the Nišlia Wolf that is consecrated through generations

...

Ivko comes broken-hearted, sits against his will and participates in the Wolf's slava, as an invited good guest. Now he sees Svetislav the idler and asks:

– Па коj je па таj.

His friends look around and shrug their shoulders.

Serb flocking from beyond Morava in the exotic Serbian region

has been en masse.

Whoever got detached from somewhere hurried to take roots here. The Serbianisation had to become in the most certain way – by marrying into the family. Svetislav introduces himself to the mayor as a good clerk and the latter takes him in his trust. He appoints him immediately as a clerk in the Municipal House, gives him an advance payment and even agrees to solicit for him to marry the pretty Mariola. Once decided, this is done. Everything goes quickly. Ivko and his wife go at once to ask the girl from her parents and come back joyful ...

It turns out, however, that the young Šumadian bridegroom doesn't have even a hat on his head ... They loan him the guard's hat an take him to the bride's house.

Thus, Ivko gets rid of his guests. On parting, he kisses Svetislav movingly

on the forehead and tells the party:

– Е па лака (not лаку) ви ноч. Аjд са здравље. А догодину извољте на светога Живка ... таг че ми е слава ... Че променим, ете, светитеља. (p. 171).

Here it is once again the tradition of the Nišlii slava. On St. Živko (there isn't such a saint) ...

And then for 5 years our spontaneous revolutionary Ivko advertises in newspapers that he is ill and cannot celebrate slava ... and even escaped as far as Belgrade to get rid of an imposition to which he, the old Nišlia couldn't get used and which he – and not only he – doesn't count as a family holiday that is compulsory by dint of a centuries-long tradition for each Serbian family.

The above quoted phrases and dialogues characterise the Bulgarian nationality of Nišlii that distinguish them from Šumadians (Serbs); let's quote a few phrases which are found in abundance in Ivkova slava to show some more of the Niš dialect

that is so difficult for Šumadians.

| Niš dialect | Standard Serbian |

|---|---|

| По големо девоjче станула (p. 10) | Beче девоjчица jе постала |

| Па керко, кротка да будеш! (р. 11) | Па кћи, мирна да будеш! |

| Како магаре (19) | Као магарац |

| Ако другче направиш (19) | Ако другче урадиш |

| Леле! | Jао! or Jоj! |

| Колко | Колико |

| Татко | Отац |

| А мен ми е па жал, па викам (31) | А мени jе жао па вичем |

| Елате малко да поседнеме (49) | Ходете мало да седнемо |

| Лошо ли е? (49) | Jели рђаво? |

| Хубаво си живуемо: како сол и леб (51) | Лjепо живимо ко со и леб |

| Мустачи | Бркове |

| Едно магаре из лоjзе што е, па го натоварѝ са заjаци. (69) | Jедног магарца што jе из винограда натоварих га зечовима. |

| Да ти не дава Господ ни да ги раниш, ни да ги поиш. (120) | Да ти не да Бог ни да их храниш, ни да их поиш. |

| А знаш ли што иска jоште Пеливан? (120) | А je л' знаш што jош хоће Пеливан? |

| Ама хубаво и кротко девоjченце. (120) | Али лjепо и мирно девоjче. |

| Ниjе мечка, ама нешто оште по хубаво. (120) | Ниjе мечка, али нешта jош лjепше. |

| Много лош човек (132) | Врло рђав човек |

| Ни ти с нас, ни ми па с тебе (160) | Ни ти са нама, ни ми са тобом |

| Ако не му давате девоjченце, разбираш ли? (160) | Ако не му дате девоjчицу, jел' разумеш? |

| А кум сас прасе (162) | А кум са прасетом |

Songs

Излезох да се прошетам

Низ таjа пуста Битоља

Низ евреjското махало

Низ тиjа тесни сокаци

Там видов мома евреjче

На висок чардак стоjаше (78).

Каква си красна, душице моjа (11)

Славеj пиле, не пеj рано (72)

Ракито, мори, Ракито,

Ракито тънка селвиjо

Тури ми вино да пиjем,

Да пиjем, да се опиjем ...

And while Nišlii use this eastern Serbian dialect

Šumadians in this novel speak very precise Serbian

The Cashier:

– Jе си л'га чула, Бога ти? Па бар да удеси, да се може веровати. Ловио зечове. (р. 170)

The Mayor:

– Да си мене питао, а ти вала не би дао ни да ги сечеш. Тако се ради. Па онда не знаш шта jе доста; толико jе то сладко. Ал'ко си веч поч'о онда даj бар мени таj нож да jа то ... (р. 136).

Zona Zamfirova

As you can see, our Niš character hasn't yet managed to become Zona Zamfirić.

Zona is a daughter of a chorbadjia (and her father still stays chorbadjia and hasn't yet become gazda), brought up in all virtues and faults of the esnaf morality in a Bugaraš varoš

as Šumadians previously called Niš and the other Morava towns.

All young men of Niš long for Zona. All town youth hum a little song adapted for her. She is beautiful with the graceful gait of a swan. And her diffident pride makes her dearer and more attractive. Young men want her from Filibe (Plovdiv) to Edrene (Odrin)

.

Zona seldom goes to the horo (Bg:chain dance, in Serbian it is called kolo). But even when she goes there, it is only to look down on the esnaf lads amongst whom, according to the definite opinion of her father and her foul-spoken aunts, she doesn't have a match. The horo happens on the square in front of the Kalofer (town in Bulgaria) Inn. She stays at the side, accompanied by her maid-servant, observes and pretends that she doesn't see the looks cast towards her from all sides together with concealed sighs.

The young master Mane Kuyumdjiata is the one most rapt on Zona. He has cocked his hat over nicely sticking out locks of black hair, twirled thin bachelor's moustaches, tightened with a narrow white belt over his trousers, and dances sprightly with the most beautiful maids. But his thought doesn't leave the white swan who is looking at him and perhaps admiring him, but hides all this in the proud maiden heart. Both Zona and Mane are equally objects of looks and desires. But the young master is not high-born and doesn't have a high house with a terrace and bay window, he doesn't have a yard covered with a box-tree garden in which a marble fountain is lashing out; the young master who made himself with constance and industry cannot expect to be given easily the chorbadjia's daughter. And he cannot even think about another.

Mane could despair, start drinking, and go bust. His mother, a humble and pious widow, is very worried about him and tries to marry him off to another maid if only to save him from despair. In vain. Master Mane is resolved to take Zona and no one else. His mother is in a quandary. But the poor woman can do nothing. Mane's frivolous and garrulous aunt takes on herself the difficult task and goes to the chorbadjia's house to arrange a marriage. There, of course, she is met with abuses and insinuations. But she stands no nonsense herself: she opens her big mouth for relief. With this she impedes the affair further. And Zona is intended to marry a chorbadjia's son.

At last, two Mane's friends come to the rescue. They have lived little but endured much. By their advice, a plot is made to break the pride of the chorbadjia's daughter after which the task is facilitated. One of them dresses in women's clothes and hangs about Zona's gates towards evening. Mane passes along him with a coach known to have been used for bride-stealing, takes the sham Zona and the coach rushes through the street.

The next day, the whole town already knows that Zona has been stolen and has spent the night with her abductor Mane. This awful rumour distresses the whole family of the chorbadjia. Even one Belgrade newspaper writes about the scandal. Mane plays the innocent. A blackmailing journalist comes to him and proposes to refute what is written and defend the reputation of the young master but Mane rejects his services.

The chorbadjia's son refuses to marry Zona. Zona is devastated enough even before this blow. She seldom appears in the street or the shops and begins to languish ...

Month after month drag on ...

At last, the chorbadjia himself drops by at Mane's shop a few times and invites him to become his son-in law ...

Let's now take a brief look at the language aspect of the novel because if we wish to describe all Bulgarian expressions, we have to type here the whole novel.

Words that Sremac himself put in quotes: дете, нешто, дедо-попе, дедо владика, мустачи.

Bulgarian dialect from Macedonia: збори ми (In Serbian: прића ми); татко ти (In Serbian: твоj отац); што праjте (In Serbian: шта радите); што ке ми чиниш; мори разбирам (In Serbian: разумем); ти си работи, а jа ке седнем малко.

Proverbs

Две љубеници под една мишка не се носат.

Три циганки – цело хоро, etc.

The purely Bulgarian language forms that Sremac describes in this novel together with the folk costume and other historical documents exist even to this day.

But there is more: the pages of Zona Zamfirova contain indelible family symbols like Kalofer Inn, Kazanlik rose oil, Gabrovo Monastery St. Mary, Filibe, Edirne, etc., that show the direction where Morava Bulgarians looked to. On the contrary, the hearts of Sremac's characters contain only coldness and confusion about Serbs: people coming from north and west that are strangers to their language, moral, and mental purity as well as some white-world women

without shame and moral who seduce their men. Furthermore, papers are published in Belgrade that disgrace them and torment their singular world which is so colourful, warm and intimate.

The Serbian

language of Morava Bulgarians

Bulgarians along Morava, Timok, and Nišava are obliged to speak Serbian language. But that Serbian

spoken only at official places in towns – as Serbs themselves acknowledge – is a ridiculous slang and, together with the ancient East-Serbian dialect

is another unmasking for Serbs.

In order to extinguish this slang, Serbs publicly ridiculed it in the press, and in various feuilletons and brochures. In this way, they planned to remove the telltale language forms at least in the intellectuals and the younger generations from Vranja to Požarevac. There was more than the definite article which worried Serbs; despite the creeping of many Serbian words in the vocabulary of Morava region, another very obvious Bulgarian language characteristic is the use of propositions instead of the full set of 7 Serbian noun declensions.

After the Serbo-Bulgarian War in 1885, Serbian philologists and publicists put great efforts in their struggle with the errors

in Serbian language. Thus, Jovan Bošković shows many inaccuracies in Serbian, the most interesting of which is the incorrect and indiscriminate use of declension forms. In his first volume, Bošković dwells on the 22 cases when infinitive is used and condemns the young Serbian writers who are in touch with the population of the newly-liberated

east Serbian regions.

Let's see what is the Serbian

language spoken by the new generations in Morava region from the book of M. T. Golubović. In 10 printer's sheets are contained more than 30 Niš anecdotes in broken and humorous Serbian. What follows are 3 excerpts from the Niš language. The first excerpt shows the typical Morava dialect in the speech of Kalcho, an ordinary Nišlija esnaf:

| Niš dialect | Standard Serbian |

|---|---|

Африкански заjац | Африкански зец |

| Ономад ли беше недеља? Jес' Jес', – ономад. Немам послу, па се диго рано, пре зору. Аjд, аjд, те дођо до Нишаву. Пређо ћуприjу, па уфати онаj пут покраj Кале. Идем си такоj сам, нигде жива душа. Маjку му, малко ме уфати стра од ониjа бедеми, од онеjе зидине! | Jел ономад jе била недеља? Jест, jест, – ономад. Не сам имао посла, па сам устао пре зоре. Аjд, па дођох до Нишаве. Пређох ћуприjу, па узедох онаj пут покраj Тврђаве. Идем тако сам, нигде живе душе. Маjка му, мало ме ухватио страх од оних бедема, од оних зидина! |

| Замислеjа сам се такоj, па фрљи очи на куде касарину у топџиску, море иде нешто по онаj малеџак бедем што jе до врбе. Шће да бидне, маjка му?! Утуви се да видим, па полако пођо на куд њега. Кад он, жена буђава, спазиjа ме зар, па чучнуjа куд jедну коприву, у ути'а уши. | Замислио сам се тако, па баце поглед на топџиске касарне, море иде нешто по оном малом бедеме, што jе код врбе. Шта ће бити, маjка му?! Реших се да видим, па полако пођох к'њему. Кад он, жена буђава, спазио ме зар, па чучнуо куд jедне коприве, у утиjа уши. |

| Заjац jе – не мож' друго да бидне! | Зец jе – не могуће другче бити! |

| Врну се до врбу, па осеко jедно пруче и пођо на куд њега. Нема три корака, – стану. Он мене гледа, jа њега гледам. О, маjку му, шће да бидне овоj, какав jе овоj напаст, да ме неjе нешто собаjле осотоњоле? Да не сам собаjле ступнуjа на мађиjе, jали ти на сугреби псећи, па несам пљунуjа?! | Вратих се до врбе, па осекох jедан прутић и пођох к њему. Несу били три корака, – стадох. Он мене гледа, jа њега гледам. О, маjку му, шта ће бити ово, каква jе ова напаст, jел ме jе што jутрос ...? Jе сам ли jутрос ступио на мађиjе, или на неки псећи сугреб, па нисам пљунуо?! |

| Право да ти кажем, почеше да ме избиjаjу грашке од зноj. Уплаши се. Jа мрдну мало с пруче, он се обрну, – па си пође полак' на куде касарину. | Право да ти кажем, почеше да ме избиjу грашке од зноjа. Уплаших се. Jа мрднух мало прутићем, он се окрену, – па пође лагано на к' касарни. |

| Погледа, погледа, што да правим?! | Погледах, погледах, шта да радим?! |

| Пушка ми неиjе туj. Чапа остануjа дом, а убаво ћаше куче да пође с мен тоj jутро, ама ко jе знаjа тога ђавола и коj се jе надаjа за оваj сорту заjаци!! Мисле се, мисле, па ми текну на памет што ми jе причаjа jедан оџа у турско време. | Пушка ми ниjе ту. Чапа jе остала кући, а добро хтеде куче да пође самном тог jутра, али ко jе знао тог ђавола и ко се jе надао за ове сорте зечева!! Мислих се, мислих, па ми дође на памет што ми причао jедан оџа за време турака. |

| Викаше он – Бог до го прости – Калчо бре, ашколсун што си ловиџиjа, и Султан знаje за теб', ми смо испратили абер за сви ловци из Ниш, ама много те волим и теб ћу ти испричам – такоj бива – jед'н муабет за заjци ама ће тражим да ич не збориш на други човеци – зашто ће те колем како пиле. | Причаше он – Бог до га прости – Калчо бре, ашколсун што си ловџиjа, и Султан зна за тебе, ми смо испослали позив за све ловце из Ниша, али много те волим и тебе ћу испричати – тако мора – jедан муабет за зечеве ама тражићу да никако не говорите другим људима, зашто ћу те заклати ко пиле. |

| За заjци ти не треба ни пушка ни куче него мурафет. Видиш ли заjац, паднаj на земља. А си паднаjа, – умртви се. Заjац те надуши и прилази на куд теб се по-близо. | За зечеви не треба ти ни пушка ни пас, него мурафета. Jел' видиш зеца, – падаj на земљу. А чим паднеш, – умртви се. Зец те нањуши и прилази код тебо све ближе. |

Yet, Kalcho is a simple esnaf man. Now let's see the literary Serbian

of Kole Pusha who already excels in Niš as a speaker and even as a publicist

.

Speaker

| Пуша се укачи на с'нд'к, извади артиjу и поче: | Пуша се попе на сандук, извади артиjу и поче: |

| Браћо, жене, девоjке и сви што сте обрнули главе на куд мене, тужном збору! | Брачо, жене, девоjке и сви шта се окренуле главе к мен, – тужни зборе! |

| Преди нама jе мртво тело Васка Бранковичем, бившом кметом у обштину нишку. | Пред нама jе мртво тело Васка Бранковића, бившег кмета општине нишке. |

| Родиjа се jе, како и ми што смо се родили у татка и маjку сви се знате кол'ко му jе д'нске годинама. | Родио се jе, како и ми што смо се родили у оца и маjке; сви ви знате колико му данас година. |

| Човек jе биjа, да ве не л'жем. Добар беше, с'лте за кмета неjе због меки нараф. | Човек jе био, да вас не лажем. Добар беше, али за кмета ниjе био због меке нарафе. |

| Ама има, писуjе у книге, ви тоj не знате: има ники молекулчики, ники атомчики, ники што би рекли гнидице, па се стегну како питиjе, ама Бог, сполаj на Господа – по jак jе од сви нама што смо се овде собрали како на неко свадбом. | Али има, пише у книгама, ви то не знате: има неки молекулчичи, неки атомчичи, неки што би рекли гњидице, па се стегну као пихтиjе, ама Бог – хвала Господу – jакчиjе од свиjу нас што смо се овде скупили као на неку свадбу. |

| У книге писуjе: од смрт се не мож побегне. За тоj драги моj Васком, и ми ћемо сви по теб, и jа сам ти, приjо, с jедну ногом у гробу, едва дизам, а близо сам ти при рупу, само здравjе од Бога. | У књиге пише: од смрти се не може побегне. За то, драги моj Васко, и ми ћемо сви за тобом, и jа сам ти, приjо, с jедном ногом у гробу, едва него дижем, а близо сам код рупе, само здравље од Бога. |

| Тужном збором! Испратите испратите домаћина, па да ви се врне, да Бог да, зашто сви идемо на там. | Тужни зборе! Испратите, испратите домаћина, па да вам се врати, да Бог да, зашто сви идемо тамо. |

| Добар човек како што jе биjа Васко тешком патриотом, не ће га више бидне из по међу нама. Истина, неjе биjа од моjу партиjу, ама jе биjо ак либерал. | Добар човек као што jе био Васко тешки патриота – не ће га више бити међу нама. Истина, ниjе биjо од моjе партиjе, али jе биjо ак либерал. |

Publicist

| љубезни г. уредниче! Изволте с опроштењем, да штампаш овоj исправку по законом од штампу и тоj на истом местом и онол'ко исто да будну редови, не сме да фали ни jедно словце. | љубезни г. уреднику! Изволте, с опроштењем, да штампаш ову исправку по закону од штампе и то на истом месту, и оноликом исто да буде редова, не сме да фале ни jедно словце. |

| Исправка у вашом фактичком листу Политика, а 126 д'н по Васиљицу, искочила jе jедна прикажња (а ви л'жете свет, викате га фељитон, тоj баjагим од фитиљи работа) коjа jе лажавна због своjом целином и мртвачким словом. | Исправка у вашем фактичком листу Политика, а у 126 дан по Васиљицу, изашла jе jедна прича (а ви лажете свет, вичате га фељетоном, кобаjаги од фитиљи посла) коjа jе лажовна у своjоj целини и мртвачког слова. |

| Неискачам има, да ве не л'жем, скоро три месеца. Болан сам, редко излазам на поље због сурдисување, па доде комшиjа и рече ми за тиjа фитиљони, по глав да ви искачаjу анатемници jедни, те га прати да ми купи туjа новину. | Не излазим, да вас не лажем, скоро три месаца. Болестан сам, ретко излазим на поље због сурдисување, па дође комшиjа и прича ми за тиjе фитиљоне, на главу да вам изашли, анатемници ниjедни, те сам га послао да ми купи ту новину. |

| Прочетеjа сам га и неjа тоj истина, да сам jа држаjа мртвачком словом. Тоj ми мен ич неjе на памет паднуло. Тоj ако искате да знате ко jе држаjа том беседом то jе биjа Миле Цига, другаром на покоjном Васку. | Прочетао сам их и ниjе то истина, да сам jа држао мртвачко слово. То и мен ниjе на памет пало. То ако хоћете да знате ко jе држао ту беседу, то jе био Миле Цига, другар покоjном Васку. |

For Šumadians, not only the incorrect use of declensions is ridiculous but also the Nišlian word stresses. For example: господѝне instead of Serbian госпòдине; испрàвка instead of ѝсправка; данàс instead of дàнас; ћупрѝjа instead of ћу̀приjа; каквà instead of кàква; несàм instead of нѝсам; султàн instead of су̀лтан, etc.

All this show that the Serbian varnish of Morava region is very thin and transparent and that an untouched Bulgarian soul lies beneath it.

Notes and references

Jован Скерлић.1914. Историја нове српске књижевности. Београд.

* The church Sst. Arachangels was built in 1819. The temple was gilded in the same year at the time of Archierei Most Blessed Mitropolite Mister Grigor the Bulgarian born in the town of Trən. Month of March 1837 after the Birth of Christ.

** Travellas are spirally folded ribbons which are worn at the temples near the kerchief. These adornments (kumbalbatsi) were worn also by the Macedonian Bulgarians in Solun Region.

Jован Бошковић. Скуплени спис. a series of 8 volumes, Belgrade, 1888-

Мих. Т. Голубовић. Успомене из новоослобођених краjева. Београд, народна штампариjа Обилићев венац, 1906

Что мне золото, светило бы солнышко!

ReplyDelete-Firstly as a citizen of Vranje whose family lived in that region for at least 150-200 years, I don't agree with your statements. Many expressions from Southern Serbia (regions Nis-Pirot-Vranje) are used in Kosmet. Most of them have Turkish origins.

ReplyDelete-Serbian army liberated Vranje, Leskovac, Pirot and Nis. There are documents of many people who helped Serbian army in this. Stepa Stepanovc (commander who later helped Bulgarian army in taking Jedrene in I Balkan war) formed many army militias in Poljanica - part of Southern Serbia. There were not any resistance to "ocupation" in Vranje recorded, but there were a lot resistence to Bulgarians in WWI. E.G. Kumite i Cetnici.

-Third Borisav Stankovic had written diarie. NOT ONCE he referred himselif or his family and ancestors as Bulgarians. Necista krv (Impure blood) is clearly understandable by lots of people around Serbia, Montenegro and Republika Srpska. All narations are clearly in Serbian and written with Serbian alphabet.

-Name day (Imendan in Serbia) is celebrated around the world not only in Bulgaria and Southern Serbia. ON the other hand Slava is celebrated only in Serbia, Montenegro, Republika Srpska, Maceodonia and in some part of Croatia. In other hand in Bulgaria Slava is only celebrated close to Timok region. What is that telling you? You decide.

-And last with: "Instead of proving Serbian power, the constant wars divided and destroyed Yugoslavia and left Serbs surrounded with foreign and hostile peoples, with much greater culture than theirs." you showed that this text is not objective and it's sole purpose was to demonize Serbs and glorify Bulgarians. And yet when you occupied that region in WWI and WWII you only bringed death and misery. E.G. Surdulica massacre.

Sorry for my bad English.

I appreciate your opinion although you blankly dismiss all statements made in the text (and some statements that are not made). Anyway, I do not expect everyone to agree with me in everything, and opposition is good as it helps to find the truth. This said, I find much of your criticism unfounded or a result of misconceptions that are deliberately disseminated in Serbian schools and media. I’ll take them one by one in the order they are posed:

Delete1. Firstly as a citizen of Vranje whose family lived in that region for at least 150-200 years, I don't agree with your statements. Many expressions from Southern Serbia (regions Nis-Pirot-Vranje) are used in Kosmet. Most of them have Turkish origins.

Answer: It is true that many expressions from Nish-Pirot-Vranya are used in Kosovo-Metohia. They are part of the Kosovo-Morava transitional dialect (Bulgarian-Serbian) in which there are more Bulgarian than Serbian traits (as outlined in my post http://lyudmilantonov.blogspot.com/2011/07/transitional-dialects.html). It is also true that many words have Turkish origin which is understandable as the population there have lived 500 years under Turkish yoke. After the Bulgarian liberation many of these Turkish words were replaced with Slavic ones. This process of replacement of Turkish words went on also in Serbia about 50 years earlier than in Bulgaria so that Serbs found there at the time of liberation a population that had a high percentage of Turkish vocabulary. 150-200 years ago is the time when Serbs (called Sumadians by the local population) settled en masse in these regions that are now called Eastern Serbia. They found a population of earlier settlers who were Bulgarian by their language and customs. So probably your family line comes from these “true Serbs” who came from other Serbian regions. As a whole, I do not see a basis for disagreement on the first point. What you say in this item agrees with my text and my knowledge.

2. Serbian army liberated Vranje, Leskovac, Pirot and Nis. There are documents of many people who helped Serbian army in this. Stepa Stepanovc (commander who later helped Bulgarian army in taking Jedrene in I Balkan war) formed many army militias in Poljanica - part of Southern Serbia. There were not any resistance to "ocupation" in Vranje recorded, but there were a lot resistence to Bulgarians in WWI. E.G. Kumite i Cetnici.

DeleteAnswer: It is true that the Serbian army liberated Vranya, Lyaskovets, Pirot and Nish. This happened during the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) when the bulk of the Turkish army was engaged in fighting against the Russian army and Bulgarian volunteers. In order to gather troops, Turks withdrew all their garrisons in Western Bulgaria as far as Sofia. The Serbs used this situation and marched into these Bulgarian towns without meeting any resistance. The local people truly felt liberated and helped Serbian army because the Turkish rule was very oppressive. After ousting the Turks they thought that they will live in their own Bulgarian state, either on its own or as a part of a Balkan Slavic federation. They imagined such federation as a community in which all peoples: Bulgarians, Serbs, Montenegrins, Croats, Slovenians, would live on an equal footing, with no one people trying to dominate over the others. On the contrary, since 1840s Serbia had another state doctrine, promoted by Garashanin (“Nacertanje”) which espoused Serbian expansion and domination over the Balkan Slavs complete with measures for their assimilation. Russians, although they generally cared about Serbian interests, couldn’t ignore the Bulgarian character of the population in Pomoravie and Macedonia. At the end of the war, in the peace treaty they negotiated a Bulgarian state in the ethnic Bulgarian borders (San-Stefano Bulgaria). The Great Powers couldn’t stand a strong Slavic country on the Balkans and at the Berlin Congress they flagrantly cut it into pieces and most of the Bulgarian land was given to the its neighbours. Bulgaria began to border on itself from all sides. Serbs took large part of West Bulgaria, and immediately began to pursue the assimilatory Garashanin doctrine. They forbade the population to talk their local Bulgarian dialect, to wear Bulgarian costumes, to follow Bulgarian customs, in short, to exhibit everything Bulgarian. Moreover, thanks to lay historians turned politicians like Cvijic, Novakovic, etc., Bulgaria and Bulgarians (Bulgars, бугари) was demoted to the rank of a dirty word, something despicable, something to be ashamed of. Serbs made obligatory in this region Serbian language, customs, costumes, and encouraged many Serbs from other parts to settle in the region in order to change the ethnic composition of the population. This policy hardened after the Serbian-Bulgarian War 1885 when the Serbs tried to stab Bulgaria in the back in the moment when Bulgaria tried to unite part of its territory. The Serbian army was soundly beaten and made to retreat and only the Austrians prevented Bulgaria from taking back the Bulgarian Pomoravie.

Morava Bulgarians did not take easily the change of their masters. Formerly, the Turks punished disobedience with death. Serbs used more refined methods grading from ridicule, deportation, estrangement, prison, and yes, sometimes death by hired assassins. The crime was always resistance to assimilations, and most found it easier to conform and lead their life as they can. If Serbs wanted them to celebrate slava, they would do it, if they had to learn Serbian, they would do it, if they had to change their names, they would do it. In order to succeed in life, they would never mention they are Bulgarian, and some were even so zealous that they were more „прави срби” than the true Serbs. They resented the new masters but this resentment was tempered by conformism and did not boil to such extent as to raise into organized disobedience, at least not in Pomoravie. People were afraid of repressions, and also in this region there were too many Serbian settlers from elsewhere. That’s why there is no resistance recorded in Vranya. In the Timok region it was different. There resentment ran higher, and there were fewer Serbian settlers. That’s why the resentment spilled itself in the Zajcar uprising, which was crushed by the Serbs with great cruelty.

DeleteThat’s how the words of Vasil Levski materialized in practice. When he was in Belgrade with the Rakovski legia in 1850s, Levski saw through the real Serbian intentions and attitudes towards Bulgarians. He said: “Beware of anyone who intends to “liberate” us. This liberator will become our new slavemaster.” The Bulgarians around Morava and Timok tried many times to liberate themselves from Turks in 19 c. Each time Serbs instigated these rebellions and each time in the decisive moment they withdrew their support leaving the population to be massacred by the Turkish army and bashibazouk. A typical example is the Nish uprising in 1841 when the whole population in Nish and surroundings was killed by the Turks. But this is a topic for another post with many more specific details.

3. Third Borisav Stankovic had written diarie. NOT ONCE he referred himselif or his family and ancestors as Bulgarians. Necista krv (Impure blood) is clearly understandable by lots of people around Serbia, Montenegro and Republika Srpska. All narations are clearly in Serbian and written with Serbian alphabet.

DeleteAs said in the text, Borisav Stankovic made an effort to write in literary Serbian in which he was partly successful. He was reproached by critics for his failure to learn well this language, foreign to him. He rewrote Kostana to make it more Serbian sounding. Generally, he succeeded in his efforts, and his narratives were close to literary Serbian and well understood by Serbian readers. Stankovic, however, persisted to introducing local dialect into the dialogues, to make his works real and authentic. He never mentioned he is Bulgarian because he wanted to succeed as a writer. In the circumstances, every such mention would throw him out of the writer’s guild, or in jail. He was observer and “photographer”, not a revolutionary. Nevertheless, his works describe very well the true feelings of Morava Bulgarians. As for Serbian alphabet, it is in fact Bulgarian alphabet in which Vuk Karadzic put a few Latin letters (see http://lyudmilantonov.blogspot.com/2011/04/bulgarian-alphabet.html).

4. Name day (Imendan in Serbia) is celebrated around the world not only in Bulgaria and Southern Serbia. ON the other hand Slava is celebrated only in Serbia, Montenegro, Republika Srpska, Maceodonia and in some part of Croatia. In other hand in Bulgaria Slava is only celebrated close to Timok region. What is that telling you? You decide.

DeleteName day is not celebrated around the world though it is celebrated in some European countries including Bulgaria and Serbia. Slava, in its typical form, is celebrated in Serbia, Montenegro, and parts of Bosnia and Croatia, and everywhere compact masses of прави срби live because this custom is considered by them a symbol for Serbishness. The Bulgarians in Macedonia do not celebrate slava, unless you want to call that their custom srekja which, however, is something very different. I am not aware of anyone celebrating slava in Bulgaria. Celebrating slava in Timok (Vidin) region does not tell me anything unless I see evidence about this. And how slava is celebrated by Morava Bulgarians, you can best see in “Ivkova slava”.

5. And last with: "Instead of proving Serbian power, the constant wars divided and destroyed Yugoslavia and left Serbs surrounded with foreign and hostile peoples, with much greater culture than theirs." you showed that this text is not objective and it's sole purpose was to demonize Serbs and glorify Bulgarians.

DeleteMy intention was to show that when one covets what belongs to others he loses what belongs to him. Still, I don’t like the way this is written because it sounds too much like gloating, and I do not mean that. I strongly opposed NATO bombing of Serbia and killing innocent people. These people were not guilty of the chauvinism and atrocities perpetrated by past Serbian rulers and their thugs. Bombing of churches and monasteries with bombs wearing the words “Happy Easter” was especially outrageous. So I will remove or replace this text.

6. … there were a lot resistence to Bulgarians in WWI. E.G. Kumite i Cetnici.

Delete… And yet when you occupied that region in WWI and WWII you only bringed death and misery. E.G. Surdulica massacre.

I suppose this refers to the so-called Toplica uprising (Топлички устанак), and the lies and falsifications about it in Serbian textbooks.

This attempted mutiny was organized by Serbian officers and lasted from February 21 to March 25, 1917 during the conquest of Bulgarian Pomoravie in WWI. Its aim was to create armed clashes and sabotage in the rear of the Bulgarian army, located on the Southwestern Front in Macedonia.

Bulgaria included Morava region in an administrative region and developed pension, education, bureaucracy which was composed of local residents. Some residents of the Moravian region received aid in money via Bulgarian Bank Agency in Nish. Many residents of Moravian region were seeking their loved ones lost in the war with Astro-Hungary by Bulgarian newspapers through the Serbian Red Cross.

The conditions for this mutiny were created because after the defeat of the Serbian Army in 1915 in the Kosovo operation and escape of Serbs to Korfu, Bulgarians did not capture the surrendering Serbian soldiers and officers as POW, and left them free to organize guerilla bands (чети) in the Bulgarian rear. The leaders were Serbian and Montenegrin officers – Capt. Kosta Pecjanac, Capt. Kosta Vojnovic, Lieut. Aca Piper, Army Priest Dimitar Dimitrevic-Mita, Dusan Kasap, Capt. Milenko Vlahovic, and others.

In September 1916, at the height of the offensive against Romania, the Entente managed to bring Capt. Kosta Pecjanac with an aircraft in Toplica Region. He was an old figure of the Serbian Chetnik organization. The goal was to raise an anti-Bulgarian rebellion, thereby destabilizing Bulgaria and helping Romania in the war. There Pecjanac associated with Vojnovic, whose base was the village Gъrgur. The decision for this rebellion was taken in the village of Konyuvtsi 09-11.02.1917. On February 21, 1917 near the river Toplica the rebellion broke out. The following methods were employed by the organizers of this rebellion:

1. People are misinformed that the Bulgarian government wants to enroll youths in the Bulgarian army, whereas the Bulgarian administration actually wanted to organize the Pomoravie young people between 18 to 20 years for road works and harvesting of fields, and not enroll them in military service;

Delete2. A rumor was spread that the Entente has reached Skopje and Kumanovo, so people should rise in revolt in the rear of the Bulgarian Army;

3. A mass terror on the local Bulgarian population in Pomomoravie was applied by the Chetniks to force the locals to raise in arms against Bulgarians. Examples: in the village of Tulari the Chetniks Milenko Vlahovic and Dimitar Dimitrevic slaughtered 80 men of the village in one week. The second week another 40 men were slaughtered for a total of 120 men. The practice was indiscriminate - Pecjanac rebels killed a priest from the village Dubatsi, and they burned living women and children. The names of these chetniks were brothers Sima and Glisha Binovic, Dragoljub Timoteevic-Lazovic, Teodosi Pavlovic and Voyo Banović. These data are shown in correspondence between the leaders Kosta Pecjanac, Mita Dimitrevic and Aca Piper. This became known to the Bulgarian authorities after the capture of Mita Dimitrevic and Aca Piper.

The leaders gathered 500-600 rebels who conquered Prokuplje, Kurshumlia and Lebane village which were guarded and administered by local militia. Voinovic chetniks acted in the region of Kopaonik and Kurshumlia, Pecjanac in Prokuplje region and Milinko Vlahovic headed to Vranya. Pecjanac attempted to attract Albanians on his side. On 28 February, he began negotiations with the Albanian leaders, but without success. Albanians attacked the Serbian chetniks. Pecjanac cheta headed to Lyaskovets, but at the village Petrovec he was is defeated by Bulgarian troops. In March 1917 he managed to capture Kurshumlia. On May 15, Pecjanac entered the Bulgarian border and invaded Bosilegrad. His cheta burned the villages Upper Lisina, Rъzhana and Bosilegrad itself. Almost the whole city was burned, killing 32 Bulgarians and two children burned alive. He then withdrew to Kosovo acting in areas controlled by the Austro-Hungarians - Pecs, Metohija and Sandzak.

On March 12, the Bulgarian counterattack started led by Col. Alexander Protogerov and Peter Darvingov involving forces of IMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation) led by Tane Nikolov. Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian authorities work together. After days of fighting, the Bulgarian army entered Prokuplje on 14 March and Austro-Hungarians - in Kurshumlia. As of March 25, the order there was fully restored.

In October 1917 the Austro-Hungarian command created entirely Albanian para-militaries to capture the Serbian rebels. In December 1917, Voinovic was killed, but Pecjanac escaped.

There were also Serbian counter-cheta that fought in the service of the Bulgarian Army. This is the cheta of Kosta Vukovic. This cheta together with the Bulgarian army, on 15 - 16.10.1917 defeated the cheta of Kosta Voinovic as 36 of his chetniks were killed, but 4 escaped including Voinovic. In the battle, however, his lover Danica was murdered.

A practice of Serbian leaders was to bring their lovers in cheta. For example, Dusan Kasap surrendered to the Bulgarian authorities together with his intimate girlfriend Savka.

Serbian and Yugoslav historiography talk about 20,000 killed during the suppression of the uprising putting the blame entirely on the Bulgarian “occupier”. In fact, the total killed are 2,400 (1,500 Serbs and 900 Bulgarians) which was mainly casualties of military action. There were some civilian Serbs killed in Prokuplje and Kurshumlija during the suppression of the rebellion, but not in Surdulica. At that time Surdulica was populated by Bulgarians and not by Serbs.

I am really impressed with your ability to spin certain facts to prove that people who have never been Bulgarians and actually suffered from Bulgarians greatly during the two World wars, are, according to you Bulgarians. O tempora o mores… I wonder why is your article written in English? The only plausible answer to me is that the reason was to write a piece of propaganda to vilify Serbians.

ReplyDeleteThe Serbian language as well as Bulgarian has a number of dialects and even at present times not everyone speaks the literary language in both countries. Both languages are of Slavic origin and similar to the point of understanding everyday life conversations without interpreters. Before literary languages were established transition between the two languages was not abrupt and that is known in linguistics as continuum of dialects. Since Vranje is close to Bulgaria it is not strange that some words are used on both sides of the border. That does not mean that people of Vranje or Niš are Bulgarians. That is a rediculous claim. Furthermore, in your pseudo-linguistic “analysis” you are skilfully avoiding facts that all Serbian dialects are, for example, use sounds đ and ć that do not exist in Bulgarian. It is quite obvious that in any country school system tries to establish use of literary language. Therefore, in Serbia it was use of all seven cases (declinations). In the language of Southern Serbia of 19th century number of declinations was reduced, however in literary Bulgarian cases do not exist at all.

To prove your nationalist aspirations, among other things, you have used wrong translations into “standard” Serbian. For those who do not speak neither of aforementioned languages and read your blog it can be quite misleading. Your passage on smoking is one of numerous examples of pretentiousness. That word ćuruti has never been widely in use as piti or pušiti, therefore difficult to understand to many people. And I can go on and rebut your claims that are in based on selective use of Serbian synonyms, pretentious or wrong translations to prove “Bulgarian” nature of southern Serbian dialects.

The most outrageous thing in your blog is writing on Slava, particularly the picture of candle, kolyvo and Slava cake surrounded by Bulgarian national colours. Slava or Služba is a holiday celebrated in the areas populated by Serbs or those who are of Serbian heritage. It is a fact not a myth as you are trying to explain. During terror of Bulgarian exarchy in 19th century Macedonia, great effort was put to eliminate celebration of Slava among population. That was purposely done to erase Serbian ethnic ties of the Macedonian population. In some parts there was success, however, village Slava (selska Slava, селска Слава) remained. Bulgarian agent Marko Cepenkov in one of his secret reports to Bulgaria writes that people of Prilep celebrate Slava “royally”.

During World War I, the Bulgarian troops under the command of first lieutenant Protogerov were ordered to inflict reprisals upon the population east of Kumanovo for an attack made on some Bulgarian troops. Before the reprisal measures begun, the entire population declared that it was Bulgarian, purely in order to avoid being punished. Protogerov was greatly perplexed. Here is a quote by Gilbert in der Maur regarding this event:

"Then Protogerov's aides had an idea: they asked who celebrated Slava. Those who did so were shot, since the celebration of Slava is a sign that one is a Serb. It is a custom which the Bulgarians do not have".

Gilbert in der Maur "Jugoslawien einst und jetz" Leipzig-Vienna, 1936,pp.330

Slava or Služba, whatever name is used is the same holiday. The basics are everywhere the same and they are shown in your picture. Differences are minor and do not change essence of the Serbian holiday. Your statement that celebration of Slava was imposed to anyone is not based on any facts as, by the way, most of your statements.

I have talked to many people from the region and I was left with the impression that the methods employed for assimilation of Bulgarians are outrageous. I have read also many books on the topic and I know much more things about the true Serbian history than you can imagine. On the contrary, your statement that "Bulgarians are a Turkish tribe" shows that you know nothing about Bulgarian history, ethnos and culture. So I have nothing more to say except to advise you to elevate your history knowledge. The present blog is a step towards this end.

ReplyDeleteI believe the areas of southern and eastern Serbia, Kosovo (from Pristina to prizren, gnilanje, vitina & kosovska kamenica) & northern macedonia (kumanovo, tetovo, Skopje), these are inhabitants that during the last 1000yrs never truly had an ethnic conscious. Its apparent in their torlak language. My family is from tetovo, and never in the last 400yrs has anyone ever declared bulgarian. Yes, we speak a torlak dialect, wth a serbian accent and macedonian grammar. Our words are 70% old serbian and slavonic and the rest (razbiram, deka, sega etc) macedonian/bulgarian. Churches in this part of macedonia were built in honor of serbian kings, and serbian kings came through our villages in the 13th century. King Petar came to our village after ww1 do bless the opening of our village church sv petka. He also donated money for the building of a huge school named Vojvoda Misic (name changed after ww2), & he visited another village next to ours to visit a vojvoda named Atanasije Petrovic. He also paid visit to another macedonian serb in tetovo named stojan, because stojan helped carry the king through albania, and when the king wanted to surrender Stojan fought and kept convincing the king not to.

ReplyDeleteSo, while we southerners are not original serbs like the dalmatians and bosnian serbs, we picked up an ethnic serb consciousness voluntarily and joined the serbdom realm and gave lives in all wars. We may look different, talk different, have a different mentality but it doesnt make us bulgarians if we dont feel or ever declared ourselves as ones.

Thx

Thank you for your comment which is filled with dignity. I respect your choice to integrate into Serbian nation to become a good citizen and contribute to the Serbian society and state. It is normal and good when this choice is made voluntarily. The characters in the above works (e.g. Ivko) also try to integrate. They "do as the Serbs do". Such are the circumstances and none is to be blamed for it. History, language, customs, etc. tell that these people are Bulgarian but this is in the past and obliterated. Life would be easier if this is forgotten.

ReplyDelete