The Battle of Pliska which is better known in Bulgaria as the Battle in Vъrbitsa Pass (Bulgarian: Битката във Върбишкия проход) was a series of battles between Bulgaria governed by knyaz Krum, and troops gathered from all parts of the Byzantine Empire led by the Emperor Nicephorus I Genik. The Byzantines plundered and burned the Bulgar capital Pliska which gave time for the Bulgars to block passes in the Balkan Mountain that served as exits out of Bulgaria. The decisive battle took place on July 26, 811, in some of the passes in the Eastern Balkan Mountain, most probably the Vărbitsa Pass. There, the Bulgars used the tactics of ambush and surprise night attack to effectively trap and immobilize the Byzantine Army, thus annihilating almost the whole army, including the Emperor. After the battle, Krum encased Nicephorus's skull in silver, and used it as a cup for wine-drinking. This is probably the best documented instance of the custom of the skull cup.

The battle of Pliska was one of the worst defeats in Byzantine history. It deterred Byzantine rulers from sending their troops north of the Balkans for more than 150 years afterwards, which increased the influence and spread of the Bulgars/Bulgarians to the west and south of the Balkan Peninsula, resulting in a great territorial enlargement of Bulgaria.

Knyaz Krum holding Nicephorus's skull

Initial campaigns

Kanasubigi Krum (796-814)

During the rule of knyaz Krum the centralization of the knyaz's power reached its peak. The Bulgars did not limit their wars only to Byzantium; they also waged wars in the west of the Balkan Peninsula, and those wars transformed from defensive to aggressive and invasive. During the first years of his rule, Krum had to attend to his north-west borders where at the beginning of the 9th century the political situation changed due to the expansion of the Frankish Empire in the Middle Danubian region and the repulsion of the weak remnants of the Avar Khaganate towards the east beyond the Tisa River after the decisive victory of Charlemagne over the Avars in 803. This last event presented an occasion for Krum to put an end to the Avar possessions.

Bulgar warriors. Scene from reenactment of the battle,

26 July 2006. Photo credit: Klearchos Kapoutsis

In 805, the Bulgars killed and captured the remaining Avars, and annexed their lands in today's Eastern Hungary and Transylvania to Bulgaria. The Bulgars put the kagan to flight and captured a host of Avar soldiers; years later, the latter would serve in the Bulgars' wars against Byzantium. The Slav tribes that lived in those lands, after being freed from the Avar rule, recognized the power of the Bulgar knyaz. [13] Thus the Bulgarian state became a neighbour of the Frankish Empire, with the recognized border starting from the estuary of Sava upstream on the Danube to the Tisa River, then upstream the whole length of the Tisa and along the Prut River to the North Besarabian trench at Leovo, along this trench which in the east reaches to the Dnester River near the town of Benderi to the south-east, finishing at the Black Sea coast. Of course, given those borders to the northwest, it is beyond doubt that the Bulgars had succeeded in annexing the lands along the Mlava and Morava Rivers to the border of the Servian tribes; the expansion of Bulgaria in this direction happened earlier together with the gradual subsiding of the Avar rule there in the 8th century. [8]

Heavily armed Bulgar soldier

In parallel with his policies to the north west, Krum also paid attention to the events in Byzantium. The political struggle of the Slavs trying to free themselves from Byzantine rule, that began during the co-reign of Constantin VI and his mother Empress Irene, was put down by the strategos Stauricius in 783-784; he succeeded in reestablishing the Emperor's power over the Slavs. When Nicephorus I became emperor in 802, Slavs renewed the struggle for independence. Taking advantage of the difficulties of Byzantium because of the unsuccessful wars with the Arabs (Saracens), on the one hand, and the general discontent in the Empire due to the ill-timed financial reforms of the Emperor, on the other, the Slavs started a revolt with the same goal as 20 years previously: to secede from Byzantium.

One of the main episodes in this struggle was the uprising of the Peloponnese Slavs in 805 (or 807) who plundered and devastated the neighbouring villages, occupied the outskirts of the town of Patri, and besieged the town, in alliance with the Arabs. However, the siege was unsuccessful and the Slavs were defeated. The Byzantines thought that their victory was entirely due to the blessing of the Apostle Saint Andreas, the patron of the town of Patri. When Nicephorus learned about this, he decided that, because the victory was achieved thanks to St. Andreas, all the trophies, taken from the Slavs belonged to him, the Emperor. After that, he ordered that all Slavs who besieged Patri, together with their families, kins, and possessions, be bound to the soil of the church St. Andreas in the Patri Mitropoly. From then on, the Slavs belonging to this mitropoly were obliged to pay the expenses of the strategos, archons, patricians, and all dignitaries, sent by the Emperor to the church land. The fate of the Peloponnese Slavs signaled to the other Slavs in the Empire, that a similar fate could be expected by them if they did not immediately receive help from the outside. Such help they could receive only from the Bulgars who were already a force to be reckoned with on the peninsula. On their side, the Bulgars did not miss an occasion to show their readiness to help, especially towards the Macedonian Slavs.

Such relations between Macedonian Slavs and Bulgars can be surmised from the expedition of Nicephorus against the Bulgars in 807. He only reached Adrianopolis (today Edirne), a Byzantine town close to the Constantinopolis, returned back to the capital, and canceled the campaign after learning of a conspiracy by the courtiers and military against him there. Theophanes [1] presents this expedition as senseless; however, the reason can easily be found in the relations between the Macedonian Slavs and Bulgars. That abortive attack, however, gave reason for the Bulgar knyaz Krum to undertake military operations against the Byzantine Empire. The main objective was an extension to the south and south-west. In the next year a Bulgarian army penetrated the Struma valley and defeated the Byzantines. The Bulgarian troops captured 1,100 litres (360 kg) of gold, earmarked for soldiers' pay, and killed many enemy soldiers including all strategos and most of the commanders because they were gathered to receive their pay. [1] According to the calculation made by Warren Treadgold, the amount of gold captured by the Bulgarians represented the salary of 12,000 people. [32, p. 157] The figure represents, most likely, the actual forces the emperor deployed in the region known to Bulgars as Lower Moesia. It is scarcely possible that this surprising attack had been undertaken only for robbing gold; on the contrary, as with the similar attack of 789, one can see a systematic effort by the Bulgars to penetrate towards the Aegean Sea and detach the western regions of Byzantium. However, the Bulgars' access to Lower Moesia was blocked by a series of fortified Byzantine points from western Thrace, first of all, by Serdica, which, given its military-strategoic significance, would become the next policy objective of knyaz Krum. Therefore, the Bulgars wanted to weaken this military centre, which is supported by the fact the in the spring of the following year, Krum undertook a serious military expedition in the same direction. Just before Easter in 809 the knyaz besieged the strong fortress of Serdica (today Sofia) and seized the city, killing the whole garrison of 6,000. [11, p. 342]

Nikephoros reacted by organizing a campaign against the Bulgars, launched in April 809, with the aim of reconquering and rebuilding Serdica. Its development is presented briefly and confusingly by Theophanes the Confessor: Nikephoros, recorded Theophanes, pretended to go campaigning against him [Krum] on the day Tuesday of Passion Week [April 3], but he did not achieve anything worthy of notice. When the officers who had escaped the massacre asked him for a promise that they would be protected, he refused to give it to them and thus forced them to desert to the enemy, among them the spatharios Eumathios, war machine expert. To his great disgrace, Nikephoros tried to convince the Imperial Citadel [Constantinople] by holy oaths, that he celebrated the Feast Passover in the camp of Krum (αὐλῇ τοῦ Κρούμμου)

. [1, p. 484] Going through the text of the Chronicles reveals, without a doubt, the fact that its author himself expresses serious reservations about the veracity of the information concerning the success achieved over the Bulgars, communicated by Nikephoros in Constantinople. Despite this fact, the information contained in the Chronicle of Theophanes received different interpretations from the researchers who approached aspects of the Byzantine campaign against the Bulgars in the spring of 809.

Bulgarian historian Vasil Zlatarsky accepts as absolutely plausible the reservations formulated by Theophanes of the news conveyed by the emperor Nikephoros to Constantinople, announcing a military success in a campaign in which he achieved nothing [8]. His interpretation of Theophanes is that as soon as Nikephoros learned of the fate of Serdica, he hastened to go out "just for appearance", as Theophanes puts it, against the Bulgarians on Tuesday of Passion Sunday (April 3), but this time too without success; he even refused to receive with him the archons who had escaped the massacre at Serdica, although they begged for pardon, and this, of course, forced them to seek refuge with Krum himself; among them was an experienced mechanic, Spatarius Eumatius. With such inaction, Nicephoros still tried with documents to assure in Constantinople that he allegedly celebrated Easter in the palace (ἐν τῇ αὐλῇ) of Krum, which he did only to distract the attention of the citizens of the capital from the discontent in the army. [1, p. 485] However, he could not avoid the latter. When the emperor wanted to restore Serdika, which had been abandoned and devastated by the Bulgars, with the help of his soldiers and thereby make up for his inactivity, but at the same time, fearing that the army would not obey his order, he tried through stratagems before the archons to convince the army itself to ask the emperor for the restoration of the city. But the soldiers, realizing that these were tricks of Nicephoros himself, raised a terrible rebellion against him and the generals. At first Nicephoros tried to quell the rebellion with the help of the military leaders, most of whom he managed to attract to his side, and then he himself assured them with terrible oaths that he cared for their welfare and that of their children. These exhortations had an effect on the soldiers and the rebellion was subdued. After that, the emperor immediately left for Constantinople, ordering the patrician Theodosius Salivara, his most trusted person, to find the main rebel leaders, and when the troops returned, he punished all the culprits of the rebellion with various punishments, "by trampling, says the chronicler, the terrible oaths he gave”. [1, p. 485-486]

Zlatarski notes that Theophanes does not specify where Nicephoros' route was directed and he opposes Bury, who interprets Theophanes as the emperor first descended to the mountains through Mileona and Markelli and reached Pliska through the Veregava pass

, pointing out that the plundering of Pliska was retribution for the destruction of Serdika, to which he looked in order to resume. It is not established, says Bury, which road he took, but he avoided meeting the victorious enemy

[11, p. 342]. According to Zlatarski, such conclusions can hardly be drawn from the quoted phrase. Even if we assume that Nicephoros went straight to the residence of the Bulgarian knyaz, we still have no reason to claim that the emperor really robbed Pliska. On the contrary, taking into account, on the one hand, the inaction of Nicephoros, and, on the other hand, the fact that the campaign itself, according to Theophanes, was "for appearance", it becomes clear that the chronicler here is ironizing the emperor, as makes him declare feats which he has not actually done. In addition, the chronicler's statement that the emperor refused to receive the chiefs who escaped the Serdica massacre at the very beginning of the campaign, and the fact that there is not even the slightest hint in the text about the movement of Nicephorus with his troops from east to west, from Pliska to Serdica, are sufficient to prove that Nicephoros set out in the direction, not of Pliska, but of Serdica, and does not appear to have reached the city itself; indeed, he had a desire to restore Serdika, which had been "abandoned" by the Bulgars, but this did not come true either, and, on the contrary, he himself was forced to return to Constantinople.

This whole story with the described rebellion shows how unpopular Nicephoros was among the army, which even in his presence raised a rebellion. Of course, these relations greatly contributed to the expansion and consolidation of Bulgarian influence. Indeed, our chronicler does not write whether Serdika was again occupied by Bulgarian troops, but it is too believable that after the departure of Nicephoros to Constantinople and the withdrawal of the Byzanthine troops, the entire Sofia region was already in Bulgarian hands, especially since we don't see the Bulgars recapturing this region from Byzantium. Be that as it may, but with the conquest of Serdika, the last Byzantine fortress in the interior of the peninsula, a free way to Slavic Macedonia was opened for the Bulgars. What great successes the Bulgars had in this direction and how dangerous they became for the empire, are shown by the new measures of Nicephoros to consolidate the imperial power in Macedonia.[8] At the opposite pole are other researchers, Bulgarian or foreign, who accept the information presented by Theophanes as false. Accordingly, they identify the "camp of Krum," with the fortress of Pliska, the residence of the Bulgarian knyaz. [7] [9] [10] [33] [34] [35] [36]

The Byzantine Catastrophy

The Pliska expedition

In 811, the Byzantine Emperor organised a large campaign to conquer Bulgaria once and for all. His preparations were long and careful; troops were collected from throughout the Empire. There was no danger from the Saracens at the moment; so he gathered an enormous army from the Anatolian and European themata with their strategoi, and the imperial bodyguard (the tagmata). The troops of the Asiatic themes had been transported from beyond the Bosphorus; Romanus, general of the Anatolians, and Leo, general of the Armenians, were summoned to attack the Bulgars, as their presence was no longer required in Asia to repel the Saracens [11, p. 343]. They were joined by a number of irregular troops, armed with slings and clubs, who expected a swift victory and plunder. The conquest was supposed to be easy, and most of the high-ranking officials and aristocrats accompanied Nicephorus, including his son Stauracius and his brother-in-law Michael I Rangabe, all patricians, commanders, officials, all divisions, and commanders' sons who were above 15 years of age of which last he composed a division of his son, and called them Worthies (Hikanatoi). [2, p.148] The whole Byzantine army is estimated to have been up to 60,000 [14] or 80,000 [15] soldiers.

Byzantine camp. Scene from reenactment of the battle, 26 July 2006. Photo credit: Klearchos Kapoutsis

In May 811 [17], the great expedition left Constantinople, led by the Emperor himself and his son, Stauracius, and set up camp at the fortress of Marcelae (present-day Karnobat) near the Bulgarian frontier where it stopped to gather the various detachments coming from the different parts of the Empire. The period of stay at Marcelae is not known: estimates range from several days to several weeks. Judging from the fact that the Byzantine Empire was very large and time was needed especially for troops from Asia (e.g. the Armenians), it is safer to take the higher estimate, which supposes that the stay at Marcelae took the better part of June and/or early July. This is confirmed by the events that happened at Marcelae. After learning that such a large army was gathering at his border, Krum assessed the situation, estimated that he could not repulse the enemy, and sent ambassadors to Marcelae begging humbly for peace which Nicephorus haughtily rejected; he was distrustful of Bulgar promises and confident of victory. [9, p. 56] Theophanes disapprovingly writes that the Emperor was deterred by his own "ill thoughts" and the suggestions of those of his advisors who were thinking like him.[1, p. 486] Some of his military chiefs considered the invasion of Bulgaria to be imprudent and too risky but Nicephorus was convinced of his ultimate success, counting mainly on the luck and wisdom of his son Stauracius. At this time, a courtier close to Nicephorus, by the name of Byzantios, escaped from Marcelae for unknown reasons and went to Krum, taking with him the Imperial apparel and 100 litres (about 33 kg) of gold; many considered this as a bad omen for Nicephorus.

Another bad omen was the unfavorable period of the year, coinciding with the heliacal rising of Sirius, the Dog Star. [16] "It was the devastating rising of the Dog" [1, p. 486], the Dog Days, considered to be an evil time "when the seas boiled, wine turned sour, dogs grew mad, and all creatures became languid, causing to man burning fevers, hysterics, and phrensies". [17] To Greeks this signified certain emanations through which the Dog Star exerted its malign influence. People suffering its effects were said to be 'star-struck' (astroboletos). [18] The Dog Star caused a "reckless bravery of the impertinent coward [Nicephorus]" and made him behave like a madman, frequently shouting challenges and then realizing that some supernatural power, "God or his enemy" (the devil), pulled him against his will. [1, p. 486]

The sky above Pliska at dawn, 03:06 a.m. on July 23, 811. [19]

The march towards the Bulgarian capital Pliska is not well described. Traditional historical treatments follow Theophanes who records that Byzantines penetrated Bulgarian territory on July 20 [20], [8, p. 331], [21].

At the time of the battle, the Bulgarian border was situated to the south of the Balkan Mountains, and Krum controlled important towns and garrisons on the southern side, including some that were very close to Marcelae. It is probable that by "Bulgarian territory" Theophanes means the lands north of the Balkan, since it is hard to imagine that a Byzantine historian would acknowledge a barbaric tribe owning land that has always been considered part of Byzantium. During the first millennium, the territory of northern Bulgaria (Moesia) was covered with an unbroken forest, known in Europe as Magna Silva Bulgarica. The forest was especially dense and impassable in the discussed region: Veregava and the plains and valleys at its foothills. It further slowed the march: the large army moved in columns along the narrow forest paths, the cavalry frequently dismounting at the steep slopes. Because this was a hostile territory, light cavalry scouts were sent ahead to spy out the army's line of march, the position of enemy forces and fortifications, the availability of wood and water, fodder and food, and were responsible for providing the commanders of the Byzantine forces with sufficient information for them to plan their route and the marching camps.

Above: Emperor Nicephorus

enters Bulgaria with his army.

Below: The captured Nicephorus

is presented to Krum.

Miniatures from the

Mannasas Chronicle.

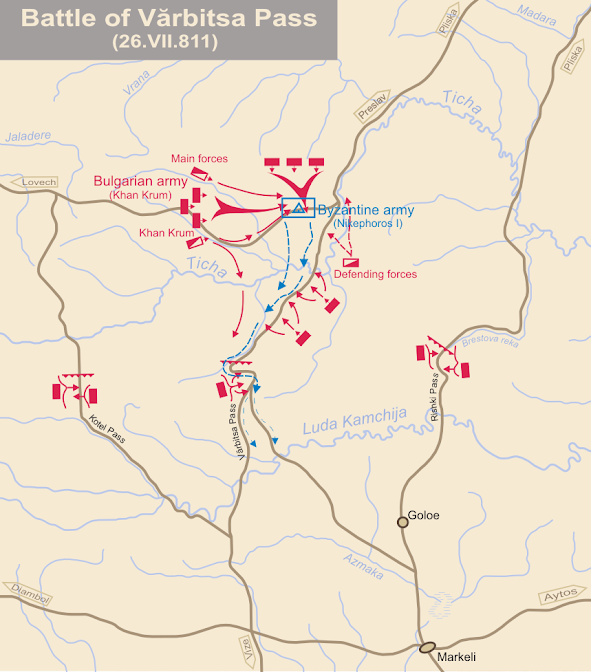

An additional impediment to the march in the form of a natural barrier was the Balkan, a 550 km long mountain chain running from Timok River in the west to the Black Sea in the east, which forms the central backbone of modern Bulgaria, and divides it into Northern and Southern parts. Known in various times as Haimos (Greek, derived from Thracian word "saimon" meaning 'mountain range'), Haemus (Latin, with the meaning 'bloody'), Balkan (Turkish, 'mountain'), Stara Planina (Bulgarian, 'old mountain'), this mountain has a great geographic and historic significance. The Zlatitsa and Vratnik passes divide the Balkan in three parts: Western, Middle, and Eastern. The lower, Eastern part, known in the 6-11 centuries as Veregava (Bulgar, 'the chain'), or Matori Gori (Slavic, 'mother mountains') stood between the meeting place of the Byzantine troops (Marcelae) and the Bulgar capital Pliska. The only way to cross the mountains is to move along the narrow passes closest to Marcelae. There are four possible routes: Rish, Vărbitsa, and Kotel passes, and the region between the confluence of the rivers Luda Kamchia and Ticha (Big Kamchia), some 20 km east of Luda Kamchia Gorge. It is known that Vărbitsa Pass was opened in 8 century, or early 9 century, at the latest [12, p.150] [8, Appendix VII, p.531]. Byzantine commanders generally preferred to cross this part of the Balkan through the then called "Veregava Pass" which is identified with Vărbitsa [22] or Rish [11, p.343] Passes.

The crossing, difficult for such a multitudinous army, would inevitably occupy some time. Approximate distances and timing are listed in the following table.

| Rish Pass | Vărbitsa Pass | Kotel Pass | Luda Kamchia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total distance [23] (km) | 91.66 | 117.18 | 145.12 | 98.75 |

| Distance in pass (km) | 12.91 | 25.85 | 25.01 | 0 |

| Time (days) | 5.54 | 7.42 | 8.94 | 5.49 |

About distances, the following must be borne in mind: while distances in the passes are relatively accurate because they were measured by following the contour of the pass, total distances are underestimated by 10-30 km because level terrain was measured on a straight line, since it is impossible to guess the exact route on level ground. For the timings, one must consider a march of 25 km to be both long and tiring for men and horses, and although this rate could have been maintained as an average in some cases, terrain, weather and the quality of the roads, tracks or paths used by the army will all have played a role, so that very considerable variations must have been usual. The average length of a day's march for infantry or combined forces was probably rarely more than 19-23 km, which has been an average for most infantry forces throughout recorded history; and this figure would more often than not be reduced if very large numbers, which had to be kept together, were involved.

The average can be increased when no accompanying baggage train is present, and increased yet again for forced marches, although there is an inverse relationship between the length and speed of such marches and the loss of manpower and animals through exhaustion. The speed at which large forces can move varies very considerably according to the terrain: anything between 11-13 km and 18-20 km per day. Cavalry by themselves can cover distances of up to 60-80 km, provided the horses are regularly rested and well nourished and watered. Small units can move much faster than large divisions: distances of up to 30 km per day for infantry can be attained. The average marching speeds for infantry are 4.8 km per hour on even terrain, 4 km on uneven or broken/hilly ground. [24] From the above mentioned, and taking into account that the Byzantine army was very large, one can take the lower estimate (18 km per day) as the rate of march, reducing it further to 11 km per day for march in a pass. Timings in the table are calculated on the above assumption; as seen, the march from Marcelae to Pliska could have taken 5.5 to 9 days. This defines the period of departing from Marcelae as July 11 to July 14, according to Theophanes [1], or July 2 to July 5, according to Scriptor Incertus [2].Nicephorus intended to confuse the Bulgars, and over the next ten days launched several feigned attacks, which were immediately called back. The Byzantines met little resistance [4, vol. 3, sheet 1, p.17] and in three days they reached the capital, where they met a 12,000 army of elite soldiers who guarded the stronghold. The Bulgars were defeated and most of them perished. Another hastily assembled army of 50,000 soldiers had a similar fate. [2, p.148-149] On 23 July the Byzantines quickly captured the defenseless capital. The city was sacked and the countryside destroyed. [6, p.372-373] [25] Knyaz Krum attempted once more to negotiate for peace:

Here you are, you have won. So take what you please and go with peace. [1, p.487]

Nicephorus, overconfident after his success, ignored him. He believed that Bulgaria was thoroughly defeated and conquered.

Byzantines attack the Bulgar stronghold. Scene from reenactment of the battle, 26 July 2006. Photo credit: Klearchos Kapoutsis

Michael the Syrian, patriarch of the Syrians Jacobites in XIIth century described in his Chronicle the brutalities and atrocities of the Byzantine Emperor: “Nicephorus, emperor of the Romans, walked in Bulgars land: he was victorious and killed a great number of them. He reached their capital, took it over and devastated it. His savagery went to such a point that he ordered to bring their small children, got them tied down on earth and made thresh grain stones to smash them.” [4, vol. 3, sheet 1, p.17] The Byzantine soldiers looted and plundered; burnt down the unharvested fields, cut the sinews of the oxen, slaughtered sheep and pigs. [2, p.150] The Emperor took over Krum's treasury, locked it and did not allow his troops to reach it at the same time cutting noses and other appendages of soldiers who touched the trophies. [26]. At the end, Nicephorus ordered his troops to burn down Krum's residence. [1, p.490] [6, p. 372-373]

The battle in the pass

Nicehorus is reported to have said: [1, p. 490-491]

Even if we had wings we could not have escaped from peril.

It must be noted that nights in this period were dark and moonless, with the moon late in the fourth or early in the first quarter, having entered the -13,746 lunation on July 24, 07:17 local time. [27] For several nights, in which they could not see even the shadows of the Bulgars that were following and surrounding them, a noise of troop movements and clang of arms kept Nicephorus and his companions in a feverish restlessness and brought them to an utter exhaustion. [1, p. 490-491] On July 26 [1, p. 490-491], Saturday [1, p. 490-491] [2, p. 152], the Bulgars gathered their troops and tightened the noose around the trapped enemy. At dawn, they rushed down and started to kill the panicked and totally confused Byzantine s, who fruitlessly resisted for a short time before perishing. Upon seeing their comrades' fate, the next units immediately ran away.

Above: The war of knyaz Krum. Below: The army of knyaz Krum chases and wounds Nikephorus's son and heir Staurakius.

In their retreat, the Byzantine forces hit a swampy river which was difficult to cross. As they could not find a ford quickly enough, many Byzantines fell into the river. The first ones stalled in the mud with their horses and were trampled by those who came next. The river was filled with so many dead men and horses that the chasing Bulgars easily passed over them and continued the pursuit. Those who passed through the river reached a wooden wall which was high and thick. The Byzantines left their horses and began climbing the wall with hands and legs and hung over the other side. The Bulgars had dug a deep moat from the outer side and when the Byzantine soldiers were getting across the ramparts, they fell from the high wall, breaking their limbs. Some of them died instantly, others hobbled some time before falling to the ground and dying from thirst and hunger. The Byzantine troops burnt the wall at several places but as they were rushing to get across it, they too fell into the moat along with the burning parts of the palisade. The anonymous narrator laments on this event, in which, it seems, most of the Worthies (the youngest soldiers) were killed:

Who will not weep when he hears this? Who will not cry? Thus perished the commanders' sons both of the old and of the young ones who were a whole multitude, in the blossom of their youth, and they had beautiful bodies that shined with whiteness, with golden hairs and beards, with handsome faces. Some of them had just been engaged to women, distinguished with nobility and beauty. All perished there: some brought down by sword, others drowned in the river, third fell from the rampart, and still others burned in the moat. Only a few of them escaped but even they, after they arrived in their homes, almost all of them died.

—Scriptor Incertus, p. 148-149

Among those killed were the patricians Aecius, Peter, Sisnius, Tryphillios, Theodosius Salivaras (the patrician Eparchos [Prefect] of the capital), Romanus (the patrician and strategos of the theme Anatolic), and many protospatharios, spatharios, and archons of the tagmata, the domesticos of the Excubitors, the droungarios of the Imperial Watch, the strategos of the Thracian army, archons of themes together with innumerable soldiers. All arms and Imperial treasures were lost. [1, p. 492] Nicephorus' son Stauracius was carried to safety by the imperial bodyguard after receiving a paralyzing wound to his neck. [1, p. 489-492] [6, p. 373]. Only a few survived the defeat, one of them being Nicephorus' brother-in-law Michael Rangabe; the majority of those who survived died shortly after they arrived at their homes.

The most notable person to be killed, however, was Emperor Nicephorus. According to Christian historians, the Byzantine soldiers hated him so much that they killed him in some way or another: some say that the Christians (Byzantines) killed him with stones after he fell down while the eunuchs in his entourage (parakoimomenous) died either in the fire of the burning ramparts or were killed with swords [1, p. 491]; either the Byzantines killed him themselves or, when the barbarians started to kill him, the Byzantines finished the killing of the torturer [6, p. 373]; in any case, Nicephorus was killed by a Roman [Byzantine]. [4, vol. III, p. 373] However, old Bulgarian sources say explicitly and unequivocally that Nicephorus was killed by the Bulgars, even by Krum himself. Thus, in the old-Bulgarian translation of the Mannases Chronicle, writing in general about the Nicephorus catastrophe in 811, one reads:

This tsar Nicephorus came into the Bulgar land during Kniaz Krum['s reign] and at first he apparently vanquished him, and plundered the estate bearing his [Krum's] name. After this, Krum gathered those who were left after the defeat, and he attacked the tsar during the night, and not only defeated the Greeks, but he [Krum] himself cut the head of the tsar, and he cased his head in silver, and poured wine in it, and he gave it to the Bulgars to drink from it. [3, p. 143]

Further in this chronicle, under two miniatures, illustrating the above text, it is written that "Kniaz Krum" caught tsar Nicephorus and cut his head. [3, p. 145]

In the Arabian Synaxarium (Prologue), that had copied the description of the said battle almost literally from the Greek Synaxarium, under the month of Tammuz (July) day 23, there is the following synopsis:

In this day, we mention our Christian brothers, who died in the Bulgar lands in the days of tsar Nicephorus who set out with his Army during the ninth year of his reign against the Bulgars, attacked them suddenly, and was deigned with victory at first, and [Nicephorus] won a great victory. But what came to pass after this, is not to be muted but deserves cry and lament. It happened so that, one night, the Bulgars taking advantage of the carelessness of the Greeks, attacked their army, killed the tsar and many other commanders. Those who received deadly blows transcended immediately from our world; those for whom the blows were not deadly hid in the wooded and overgrown places; those who were captured alive suffered numerous tortures because they refused to deny Our Lord Jesus Christ; for some of them their heads were cut with sword; others were deprived of their present life with strangling; thirds were wounded with numerous arrows and transcended from this life. As for the rest, they were imprisoned in dungeons and sentenced to hunger and thirst. In this way, they freed themselves from this world and were wreathed with martyrs' wreaths. [28]

Knyaz Krum receives the head of the Byzantine Emperor Nikephorus. Painting by Nikolay Pavlovich (1835-1894)

According to tradition, Krum had the Emperor's skull lined with silver and used it as a drinking cup. From the Byzantine (Christian) point of view, this act is an expression of the barbaric Bulgar customs, and is nothing more than sacrilege and a humiliation of Nicephorus. One must take into account, however, that according to the pagan religion of the Bulgars, the strength of the enemy, residing in his head, dissolves in the wine, and transfers to the blood of the person who drinks from the skull, making him invincible. The most powerful ruler of Europe had been vanquished, and Krum accepted his power by drinking from his skull. With this, he did not humiliate the Emperor; on the contrary, he acknowledged Nicephorus's power and wished it to be passed to himself by drinking from his skull. Evidently, Krum did not share Theophanes' opinion that Nicephorus was an incompetent commander leading a riff-raff army; quite on the contrary, Krum thought highly of the strength of the Byzantine army and the military ability of Nicephorus. As is seen by Krum's repeated humble peace proposals, he did not underestimate even for a moment Nicephorus as his adversary. There is no evidence for Krum making drinking cups from the heads of other commanders that he defeated: the Avar khagan and Michael Rangabe; probably he did not consider them great enough for these rites.

Location of catastrophe

Although historians are unanimous about the timing of the last battle, in which Nicephorus I Genik was killed (July 26, 811), there is some disagreement about the exact location of the battle. It must be noted that although Theophanes writes about this event in great detail as a contemporary and also according to the narratives of participants, he does not give any topographic names that can pinpoint the place of the catastrophe; therefore, this place is designated differently by different authors. Thus, Konstantin Jireček [12] thinks that the invasion of Nicephorus as well as his defeat happened in the Veregava and Vărbitsa Passes because the latter had been opened until 8th or 9th century at the latest. Brothers V. and K. Škorpil [29] tried to prove that the catastrophe happened in the Kotel Pass, and they even tried to place the Bulgar and Romean positions. They based their opinion on a local legend that "here Bulgars and Greeks fought, and there was a maiden named Vida, who by discerning the rampart on the near peak, facilitated the Bulgar army" and that in "Greek Hollow" (between the Vid Peak (Kăstepe) and Razboyna Mountain) fell 16,000 Greeks together with their tsar. Later, K. Škorpil softened his earlier opinion by suggesting that Nicephoras' army was returning from Aboba (Pliska) towards Vărbitsa and in Vărbitsa Pass they were repulsed by Krum towards the Kotel Pass where the fighting took place in the so-called "Greek Hollow". But immediately after this, he writes: "According to legend, the fighting between Bulgars and Greeks took place in the locality "Razboy" between the villages Krumovo (Chatalar) and Divdyadovo (on the southern slopes of the Shumen Plateau) in the vicinity of Aboba (Pliska). We think, however, that a more probable location for the fight between Krum and Nicephorus is the Rish Valley, which, being surrounded by mountains, corresponds to Nicephorus' words. Krum could retreat to Marcelae through Veregava Pass and the said valley." [30] The last paragraph shows that K. Škorpil has abandoned his earlier opinion and maintains that the catastrophe occurred in the Veregava (=Chalăka) or Rish Passes. J. B. Bury, however, thinks that Veregava Pass is not the right location of the fight: "So far as we can divine, he permitted the enemy to lure him into the contiguous pass of Verbits, where a narrow defile was blocked by wooden fortifications which small garrisons could defend against multitudes. Here, perhaps, in what is called to-day the Greek Hollow, where tradition declares that many Greeks once met their death, the army found itself enclosed as in a trap." [11, p. 344] As we see, Bury accepts the earlier opinion of K. Škorpil; however, he mistakes Vărbitsa Pass with Kotel Pass in ascribing the location of "Greek Hollow".

The following objections can be raised against the opinion that Kotel Pass was the location of the battle: First of all, it is too risky to rely on local legends for determining the location of historic events, if those are not supported, at least in part, by literature data. This precaution is necessary especially with the issue at hand, first, because such legends for Nicephorus' defeat exist in many places throughout Eastern Bulgaria (around Shumen and Preslav), not only among Bulgarian but also among the Turkish population there, and second, because those legends cannot be considered to go back to old times: they were created relatively recently, during Bulgarian Renaissance and rediscovery of Bulgarian history. This is best exemplified by the name "Greek Hollow". This name in the mouth of old Kotel citizens sounds "Grăshki" and according to some "Grishki" or "Grashki" (=Pea Hollow), or even as in Bury, "Groshki" (=Penny Hollow) so that etymology can have completely different meaning.

Without doubt, however, the best evidence can be found in the chronological data in Theophanes' account. As we saw above, Nicephorus entered the Bulgar territory through the border fortress Marcelae on July 20. The first 3 days he spent on the move in skirmishes with the Bulgars, and when he entered the mountain pass, he chose steep paths, so that on the fourth day, July 23, he could enter into the residence of the Bulgar knyaz. One cannot believe the words of Theophanes that Nicephores plundered and killed the population of the town, and then burned Krums' palaces only in one day, and immediately went back; because, as we saw, Krum, even after the plunder, negotiated for peace, probably to gain time while blocking the entrances and the exits of the pass, which happened on the 5th and the 6th day (Thursday and Friday) while Nicephorus was still in Pliska. Evidently, he left on the 6th day because on the 7th day (Saturday) on July 26 at dawn the Bulgars were already attacking Nicephorus' tent. It is hardly conceivable that in such a short time the Byzantians would reach the peaks Vetrila and Vid in the Kotel Pass and take good strategoical positions, and Nicephorus make a military camp in the locality "Karenika" in the Kotel Pass. Moreover, Nicephorus learned about the Bulgar fortifications while he was on the move and was already inside the pass, and this happened in the night of the 7th day, because if he knew before that he wouldn't want "to have wings" but would seek another way to retreat. The confusion and panic in the Byzantine army show that it was attacked without warning, so that it is unconceivable that Nicephorus would have time to fortify and choose "important positions" and, in general, to prepare for battle. All this shows that the defeat of Nicephorus happened not far from Krum's residence and this can be in the Chalăka or the Vărbitsa Passes. It is hard to say which one; however, if we take into account that Nicephorus chose the shortest way for retreat, it is more probable that Nicephorus chose the Vărbitsa pass, through which he entered into Bulgaria. [9, p.58]

On the basis of calculation of distances and speeds of movement, using partly our data plus additional measurements and considerations, Vasile Mărculeţ [31] does not agree that the battle took place in Vъrbitsa, Kotel, Rish, Veselinovo passes or in Ticha (Kamchia) Valley, and proposes, as a hypothesis, two possible new locations.

The first hypothesis has as its starting point the assumption that, after leaving Pliska, the Byzantine forces headed southwest, crossed Stara Planina via Vărbitsa Pass, following up at this point one of the itineraries they had penetrated into Bulgaria, then headed west through the passage between Stara Planina and Mt Sredna Gora. The battle could have taken place in Mărculeţ's opinion, at the western end of the passage between the two mountain ranges, in the area of Klisura, on the river Stryama, the ancient Syrmos. In this case, the Byzantine forces traveled in the 15 days of march from Pliska to Klisura about 320 km, which means a pace of movement of 22 km or 14 miles a day.

The second hypothesis starts from the assumption that, after leaving Pliska, the Byzantine troops headed west, crossed the Pre-Balkan Plateau to the Troyan area, on the upper course of the river Osъm. In Mărculeţ's opinion, the first two phases of the Bulgarian-Byzantine battles, may have taken place at the entrance to the Troyan Pass. The third phase could probably have taken place at the exit of the same pass. In such eventuality, the Byzantine forces crossed, in the 15 march days, a distance of about 290 km, having a travel pace of more than 19 km or about 13 miles a day. Through the information regarding the riches of the area, transmitted by the Scriptor Incertus [2], which reveals an agricultural region par excellence, specific to the Pre-Balkan Plateau, Mărculeţ believes this hypothesis as the most plausible. [31]

Aftermath

The defeat was the worst the empire had faced since the Battle of Adrianopol over 400 years earlier, when the Eastern Roman forces were defeated by the Visigoths and Emperor Valens himself was killed. It was a stupendous blow to the Imperial prestige—to the legend of the Emperor’s sacrosanctity, so carefully fostered to impress the barbarians. Moreover, the Visigoths that slew Valens had been mere nomads, destined soon to pass away to other lands; the Bulgars were barbarians settled at the gate, and determined—more so now than ever—to remain there. The military might of the Empire was severely crippled and the memory of this catastrophe never paled among Byzantines while the Bulgars would ever be heartened by the memory of their triumph. [9, p.58] Stauracius, the new emperor, had been wounded and was ineffectual as emperor; he was deposed and succeeded by his brother-in-law Michael I Rangabe a month later. [4, p. 17]Knyaz Krum feasts after the victory over Nicephorus I Genik. [3] Inscription (in Old Bulgarian Slavic): "Krum Kniaz encased the head of tsar Nicephores and drank to the health of Bulgars."

For Bulgaria, this victory had tremendous importance: it not only saved it from the great threat from Byzantium and returned all the lands taken from them, but strengthened all Bulgar conquests in the West together with Serdika and secured them from future attacks by Byzantine emperors, for whom Bulgaria became a permanent threat. For a long time, until the reign of John I Tzimiskes (ca. 970), Byzantines were afraid to pass the Balkan Mountains. Krum had good reason to be exultant. The whole effect of Constantine Copronymus’ long campaigns had been wiped out in one battle. He could face the Empire now in the position of conqueror of the Emperor, on equal terms, at a height never reached by Isperih or Tervel. Henceforward he would not have to fight for the existence of his country; he could fight for conquest and for annexation. Moreover, in his own country his position was assured; no one now would dare dispute the authority of the victorious knyaz. He could not have done a more useful deed to strengthen the Bulgar crown. Moreover, this victory elevated the image of the Bulgar knyaz in the eyes of Macedonian Slavs and with this opened a way for extension of the Bulgar state to the southwest. This pride of Krum is most clearly evident in the story about Nicephorus' head:

As he cut the head of Nicephorus, Krum put it on a stake for several days to show it to the tribes coming to him to our disgrace. After that he took it, plated it with silver from the outside and proudly made the Slav knyazes [princes] drink from it. [1, p. 491]

Content with their victory, the Bulgars did not at once follow it up with an invasion. But late next spring (812) Krum attacked the Imperial fortress of Develtus, a busy city at the head of the Gulf of Burgas, commanding the coast road to the south. It could not hold out long against the Bulgars. Krum dismantled the fortress, as he had done at Serdika, and transported the inhabitants, with their bishop and all, away into the heart of his kingdom. In June the new Emperor Michael set out to meet the Bulgars; but the news that he was too late to save the city, together with a slight mutiny in his army, made him turn back while he was still in Thrace. His inaction and the Bulgar victories terrified the inhabitants of the frontier cities. They saw the enemy overrunning all the surrounding country, and they determined to save themselves as best they could. The smaller frontier forts, Probatum and Thracian Nicaea, were abandoned by their population; even the population of Anchialus (today Pomorie) and Thracian Berrhoea (today Stara Zagora), whose defences Empress Irene had recently repaired, fled to districts out of reach of the heathen hordes. The infection spread to the great metropolis-fortress of Western Thrace, Philippopolis (today Plovdiv), which was left half-deserted, and thence to the Macedonian cities, Philippi and Strymon. In these last cities it was chiefly the Asiatics transported there by Nicephorus that fled, overjoyed at the opportunity of returning to their homes. Over the next two years, Krum was able to attack the empire in the vicinity of Constantinople itself, although he was never able to take the city. Michael attempted to recover from the loss, but was defeated in 813 at the Battle of Versinikia. After this victory, Krum began preparations for a direct attack against the Byzantine capital. During these preparations, according to Scriptor Incertus, he gathered a large army, including his allies the Avars and "all Slavinias" (καὶ πάσας τὰς Σκλαβινίας). [2] This fragment is very revealing, attesting to the existing military agreement between the Bulgar state and the Slavs from the Bulgar-Thracian group outside its territory who saw Bulgaria as their natural political and ethnic center. By "all Slavinias" we must understand the Slavic tribes, primarily in Thrace and Macedonia, who were still under the Byzantine rule and who hoped that after a joint attack against the then weakened Byzantine Empire they could win at last their freedom and political independency. Through his alliance with "all Slavinias" Krum followed his policy of unification which the Bulgar knyazes initiated since the beginning of 8th century and which at that moment had every chance to succeed. However, Krum died unexpectedly in 814, amid the military preparations.

Krum function in mathematics and machine learning

The growing amount of available data and complex machine learning models have led to the need for distributed learning schemes that require significant computational resources. However, distributing computation over several machines increases the risk of failures such as crashes, computation errors, stalled processes, biases in data distribution, and even attacks that compromise the system. The majority of learning algorithms used today rely on stochastic gradient descent (SGD), which involves minimizing a cost function based on stochastic estimates of its gradient. Distributed implementations of SGD typically involve a single parameter server that updates the parameter vector, while worker processes estimate the update based on the data they have access to. During each learning round, the parameter server broadcasts the parameter vector to the workers, who compute an estimate of the update, and the parameter server aggregates their results to update the parameter vector. The following problem arises in this process, called The Byzantine Generals Problem.

The Byzantine Generals Problem

We imagine that several divisions of the Byzantine army are camped outside an enemy city, each division commanded by its own strategos (general). The strategoi can communicate with one another only by messenger. After observing the enemy, they must decide upon a common plan of action. However, some of the strategoi may be traitors, trying to prevent the loyal strategoi from reaching agreement. The strategoi must have an algorithm to guarantee that

A. All loyal strategoi decide upon the same plan of action.

The loyal strategoi will all do what the algorithm says they should, but the traitors may do anything they wish. The algorithm must guarantee condition A regardless of what the traitors do. The loyal strategoi should not only reach agreement, but should agree upon a reasonable plan. We therefore also want to insure that

B. A small number of traitors cannot cause the loyal strategoi to adopt a bad plan.

Condition B is hard to formalize, since it requires saying precisely what a bad plan is, and we do not attempt to do so. Instead, we consider how the strategoi reach a decision. Each strategos observes the enemy and communicates his observations to the others. Let v(i) be the information communicated by the ith strategos. Each strategos uses some method for combining the values v(1) ..... v(n) into a single plan of action, where n is the number of strategoi. Condition A is achieved by having all strategoi use the same method for combining the information, and Condition B is achieved by using a robust method. For example, if the only decision to be made is whether to attack or retreat, then v(i) can be Strategos i's opinion of which option is best, and the final decision can be based upon a majority vote among them. A small number of traitors can affect the decision only if the loyal strategoi were almost equally divided between the two possibilities, in which case neither decision could be called bad.

While this approach may not be the only way to satisfy conditions A and B, it is the only one we know of. It assumes a method by which the strategoi communicate their values v(i) to one another. The obvious method is for the ith strategoi to send v(i) by messenger to each other strategos. However, this does not work, because satisfying condition A requires that every loyal strategos obtain the same values v(1) ..... v(n), and a traitorous strategos may send different values to different strategoi. For condition A to be satisfied, the following must be true:

1. Every loyal strategos must obtain the same information v(1) .... , v(n). Condition 1 implies that a strategos cannot necessarily use a value of v(i) obtained directly from the ith strategos, since a traitorous ith strategos may send different values to different strategoi. This means that unless we are careful, in meeting condition 1 we might introduce the possibility that the strategoi use a value of v(i) different from the one sent by the ith strategos – even though the ith strategos is loyal. We must not allow this to happen if condition B is to be met. For example, we cannot permit a few traitors to cause the loyal strategoi to base their decision upon the values retreat

,..., retreat

if every loyal strategos sent the value attack

. We therefore have the following requirement for each i:

2. If the ith strategos is loyal, then the value that he sends must be used by every loyal strategos as the value of v(i).

We can rewrite condition 1 as the condition that for every i (whether or not the ith strategos is loyal),

1'. Any two loyal strategoi use the same value of v(i).

Conditions 1' and 2 are both conditions on the single value sent by the ith strategos. We can therefore restrict our consideration to the problem of how a single strategos sends his value to the others. We phrase this in terms of a commanding strategos sending an order to his hypostrategoi, obtaining the following problem.

Byzantine Generals Problem. A commanding strategos must send an order to his n – 1 hypostrategoi such that

IC1. All loyal hypostrategoi obey the same order.

IC2. If the commanding strategos is loyal, then every loyal hypostrategos obeys the order he sends.

Conditions IC1 and IC2 are called the interactive consistency conditions. Note that if the commander is loyal, then IC1 follows from IC2. However, the commander need not be loyal.

To solve our original problem, the ith strategos sends his value of v(i) by using a solution to the Byzantine Generals Problem to send the order use v(i) as my value

, with the other strategoi acting as the hypostrategoi.

Impossibility condition

The Byzantine Generals Problem seems deceptively simple. Its difficulty is indicated by the surprising fact that if the strategos can send only oral messages, then no solution will work unless more than two-thirds of the strategoi are loyal. In particular, with only three strategoi, no solution can work in the presence of a single traitor. An oral message is one whose contents are completely under the control of the sender, so a traitorous sender can transmit any possible message. Such a message corresponds to the type of message that computers normally send to one another.

We now show that with oral messages no solution for three strategoi can handle a single traitor. For simplicity, we consider the case in which the only possible decisions are attack

or retreat

. Let us first examine the scenario pictured in which the commander is loyal and sends an attack

order, but Hypostrategos 2 is a traitor and reports to Hypostrategos 1 that he received a retreat

order. For IC2 to be satisfied, Hypostrategos 1 must obey the order to attack.

Now consider another scenario, in which the commanding strategos is a traitor and sends an "attack" order to Hypostrategos 1 and a "retreat" order to Hypostrategos 2. Hypostrategos 1 does not know who the traitor is, and he cannot tell what message the commander actually sent to Hypostrategos 2. Hence, the scenarios in these two pictures appear exactly the same to Hypostrategos 1. If the traitor lies consistently, then there is no way for Hypostrategos 1 to distinguish between these two situations, so he must obey the attack

order in both of them. Hence, whenever Hypostrategos 1 receives an "attack" order from the commander, he must obey it.

However, a similar argument shows that if Hypostrategos 2 receives a retreat

order from the commander then he must obey it even if Hypostrategos 1 tells him that the commander said attack

. Therefore, Hypostrategos 2 must obey the retreat

order while Hypostrategos 1 obeys the attack

order, thereby violating condition IC1. Hence, no solution exists for three hypostrategoi that works in the presence of a single traitor.

This argument may appear convincing, but we strongly advise the reader to be very suspicious of such nonrigorous reasoning. Although this result is indeed correct, we have seen equally plausible proofs

of invalid results. We know of no area in computer science or mathematics in which informal reasoning is more likely to lead to errors than in the study of this type of algorithm. For a rigorous proof of the impossibility of a three-strategoi solution that can handle a single traitor, we refer the reader to [40].

Using this result, we can show that no solution with fewer than 3m + 1 strategoi can cope with m traitors. The proof is by contradiction – we assume such a solution for a group of 3m or fewer and use it to construct a three-strategoi solution to the Byzantine Generals Problem that works with one traitor, which we know to be impossible. To avoid confusion between the two algorithms, we call the generals of the assumed solution Bulgarian boili, and those of the constructed solution Byzantine strategoi. Thus, starting from an algorithm that allows 3m or fewer Bulgarian boili to cope with m traitors, we construct a solution that allows three Byzantine strategoi to handle a single traitor.

The three-strategoi solution is obtained by having each of the Byzantine strategoi simulate approximately one-third of the Bulgarian boili, so that each Byzantine strategos is simulating at most m Bulgarian boili. The Byzantine commander simulates the Bulgarian commander plus at most m – 1 Bulgarian boili, and each of the two Byzantine hypostrategoi simulates at most m Bulgarian boili. Since only one Byzantine strategos can be a traitor, and he simulates at most m Bulgarians, at most m of the Bulgarian boili are traitors. Hence, the assumed solution guarantees that IC1 and IC2 hold for the Bulgarian boili. By IC1, all the Bulgarian boili being simulated by a loyal Byzantine hypostraategos obey the same order, which is the order he is to obey. It is easy to check that conditions IC1 and IC2 of the Bulgarian boili solution imply the corresponding conditions for the Byzantine strategoi, so we have constructed the required impossible solution.

One might think that the difficulty in solving the Byzantine Generals Problem stems from the requirement of reaching exact agreement. We now demonstrate that this is not the case by showing that reaching approximate agreement is just as hard as reaching exact agreement. Let us assume that instead of trying to agree on a precise battle plan, the strategoi must agree only upon an approximate time of attack. More precisely, we assume that the commander orders the time of the attack, and we require the following two conditions to hold:

IC1'. All loyal hypostrategoi attack within 10 minutes of one another.

IC2'. If the commanding strategos is loyal, then every loyal hypostrategos attacks within 10 minutes of the time given in the commander's order.

(We assume that the orders are given and processed the day before the attack and that the time at which an order is received is irrelevant – only the attack time given in the order matters.)

Like the Byzantine Generals Problem, this problem is unsolvable unless more than two-thirds of the strategoi are loyal. We prove this by first showing that if there were a solution for three strategoi that coped with one traitor, then we could construct a three-strategoi solution to the Byzantine Generals Problem that also worked in the presence of one traitor. Suppose the commander wishes to send an attack

or retreat

order. He orders an attack by sending an attack time of 1:00 and orders a retreat by sending an attack time of 2:00, using the assumed algorithm. Each hypostrategos uses the following procedure to obtain his order.

- After receiving the attack time from the commander, a hypostrategos does one of the following:

- If the time is 1:10 or earlier, then attack.

- If the time is 1:50 or later, then retreat.

- Otherwise, continue to step (2).

- Ask the other hypostrategos what decision he reached in step (1).

- If the other hypostrategos reached a decision, then make the same decision he did.

- Otherwise, retreat.

It follows from IC2' that if the commander is loyal, then a loyal hypostrategos will obtain the correct order in step (1), so IC2 is satisfied. If the commander is loyal, then IC1 follows from IC2, so we need only prove IC1 under the assumption that the commander is a traitor. Since there is at most one traitor, this means that both hypostrategoi are loyal. It follows from ICI' that if one hypostrategos decides to attack in step (1), then the other cannot decide to retreat in step (1). Hence, either they will both come to the same decision in step (1) or at least one of them will defer his decision until step (2). In this case, it is easy to see that they both arrive at the same decision, so IC1 is satisfied. We have therefore constructed a three-strategoi solution to the Byzantine Generals Problem that handles one traitor, which is impossible. Hence, we cannot have a three-strategoi algorithm that maintains ICI' and IC2' in the presence of a traitor.

The method of having one strategos simulate m others can now be used to prove that no solution with fewer than 3m + 1 strategoi can cope with m traitors. The proof is similar to the one for the original Byzantine Generals Problem and is left to the reader.

A solution with oral messages

We showed above that for a solution to the Byzantine Generals Problem using oral messages to cope with m traitors, there must be at least 3m + 1 strategoi. We now give a solution that works for 3m + 1 or more strategoi. However, we first specify exactly what we mean by "oral messages". Each strategoa is supposed to execute some algorithm that involves sending messages to the other strategoi, and we assume that a loyal strategos correctly executes his algorithm. The definition of an oral message is embodied in the following assumptions which we make for the strategos message system:

- A1. Every message that is sent is delivered correctly.

- A2. The receiver of a message knows who sent it.

- A3. The absence of a message can be detected.

Assumptions A1 and A2 prevent a traitor from interfering with the communication between two other strategoi, since by A1 he cannot interfere with the messages they do send, and by A2 he cannot confuse their intercourse by introducing spurious messages. Assumption A3 will foil a traitor who tries to prevent a decision by simply not sending messages. The practical implementation of these assumptions is discussed below.

The following algorithms require that each strategos be able to send messages directly to every other strategos. Later, we describe algorithms which do not have this requirement.

A traitorous commander may decide not to send any order. Since the hypostrategoi must obey some order, they need some default order to obey in this case. We let RETREAT be this default order.

We inductively define the Oral Message algorithms OM(m), for all nonnegative integers m, by which a commander sends an order to n - 1 hypostrategoi. We show that OM(m) solves the Byzantine Generals Problem for 3m + 1 or more strategoi in the presence of at most m traitors. We find it more convenient to describe this algorithm in terms of the hypostrategoi "obtaining a value" rather than "obeying an order".

The algorithm assumes a function majority with the property that if a majority of the values vi equal v, then majority (Vl,.. •, v,-D equals v. (Actually, it assumes a sequence of such functions--one for each n.) There are two natural choices for the value of majority(v1, ..., v,-1): 1. The majority value among the vi if it exists, otherwise the value RETREAT; 2. The median of the vi, assuming that they come from an ordered set. The following algorithm requires only the aforementioned property of majority. Algorithm OM(0). (1) The commander sends his value to every lieutenant. (2) Each lieutenant uses the value he receives from the commander, or uses the value RETREAT if he receives no value. Algorithm OM(m), m > O. (1) The commander sends his value to every lieutenant. (2) For each i, let vi be the value Lieutenant i receives from the commander, or else be RETREAT if he re :eives no value. Lieutenant i acts as the commander in Algorithm OM(m - 1) to send the value vi to each of the n - 2 other lieutenants. (3) For each i, and each j ~ i, let vj be the value Lieutenant i received from Lieutenant j in step (2) (using Algorithm OM(m - 1)), or else RETREAT if he received no such value. Lieutenant i uses the value majority (vl ..... v,-1 ).The most robust system tolerates Byzantine failures, which are completely arbitrary behaviors of some processes. A classical approach to mask failures in distributed systems is to use a state machine replication protocol, but in the case of distributed machine learning, this requires all worker processes to agree on a sample of data or how the parameter vector should be updated. However, these solutions are not satisfactory in realistic distributed machine learning settings because they entail significant communication and computational costs, defeating the purpose of distributing the work, and they do not prevent Byzantine processes from proposing updates that prevent the convergence of the learning algorithm.

However, this aggregation can be challenging to devise to tolerate Byzantine processes among the workers, as a single Byzantine worker can prevent any classic averaging-based approach from converging. In Blanchard et al. (2017) paper [37], the authors show that no linear combination of updates proposed by the workers can tolerate a single Byzantine worker, and a non-linear, squared-distance-based aggregation rule that selects the vector closest to the barycenter can only tolerate a single Byzantine worker. Two Byzantine workers can collude to move the barycenter farther from the correct area, making it challenging to choose the appropriate aggregation of the vectors proposed by the workers.

The paper [37] discusses how stochastic gradient descent (SGD) is used in various learning algorithms and its implementation in distributed settings where a parameter server broadcasts the parameter vector to worker processes that compute an estimate of the update. However, the presence of Byzantine workers, who may provide malicious updates, can prevent classic averaging-based approaches from converging. The authors propose an aggregation rule, Krum (named for Knyaz Krum (Greek Κρούμος) of the end of the eighth century, who undertook offensive attacks against the Byzantine empire. Bulgaria doubled in size during his reign), that selects the vector closest to its n – f neighbors to ensure resilience to Byzantine workers.

Krum is also evaluated experimentally and is compared to classical averaging, confirming that Krum can stand Byzantine attacks while averaging does not. Krum is also evaluated for its learning speed and is shown to perform well with a reasonable mini-batch size. The paper [37] also discusses Multi-Krum, a variant of Krum that outperforms other aggregation rules like the medoid, inspired by the geometric median. satisfies a resilience property and has a (local) time complexity linear in the dimension of the gradient. The authors show that the machine learning scheme converges under Krum, which selects only one vector, and discuss other variants.

A Krum function is an aggregation rule that is used to achieve Byzantine-resilient distributed stochastic gradient descent (SGD).[37] It is based on the Euclidean distance between the gradients proposed by different workers in a distributed machine learning system. The Krum function selects the gradient that has the smallest sum of distances to n – f – 1 other gradients, where n is the total number of workers and f is the number of Byzantine workers.[38]

More formally, let X be a set of n points in d-dimensional Euclidean space, and let x be a point in X. The Krum function Kr(x) is defined as:

Kr(x) = ∑ ||x – xi||2where xi is the i-th nearest neighbor of x, and ||.|| denotes the Euclidean norm.

The Krum function can guarantee convergence despite f Byzantine workers, as long as 2f + 2 < n.[37]

The Krum function is often used in multi-worker systems, where each worker has a set of local observations and must make a decision based on those observations. The Krum function can be used to aggregate the observations of the workers and select a decision that is robust to the presence of Byzantines (outliers or malicious workers).

The challenges of dealing with Byzantine behavior in distributed asynchronous machine learning systems, caused by hardware or software failures, corrupt data, or malicious attacks were further addressed by Damaskinos et al. (2018) [39] who proposed Kardam, the first asynchronous algorithm that can cope with such behavior by utilizing a filtering and a dampening component. As we know, Kardam was a Bulgarian knyaz who pre-empted the Byzantine empire’s invasion. He was the predecessor of Krum (Blanchard et al., 2017) [37], the Bulgarian knyaz who gave his name to the first provable solution for the synchronous Byzantine SGD problem.

The filtering component of the Kardam algorithm ensures resilience against one-third of Byzantine workers, while the dampening component adjusts to stale information through gradient weighting. Damaskinos et al. (2018) [39] prove that Kardam guarantees convergence in the presence of asynchrony and Byzantine behavior and evaluate it on CIFAR100 and EMNIST datasets. They show that Kardam induces a slowdown due to the cost of Byzantine resilience, which is less than f/n, where f is the number of Byzantine failures tolerated, and n is the total number of workers. The dampening component is also shown to be useful in building an SGD algorithm that outperforms other asynchronous competitors in environments with honest workers.

Sources

Primary sources

1. Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, Ed. Carl de Boor, vol. I, 1883, vol. II, 1885, Leipzig.

2. Scriptor Incertus. Anonymous Vatican Narration (Narratio anonyma e codice Vaticano), In: Codice Vaticano graeca 2014 (XII s.) ff. 119-122; Ivan Duychev (1936) New Biographic Data on the Bulgarian Expedition of Nicephorus I in 811, Proc. Bulg. Acad. Sci. 54:147-188 (in Bulgarian); H. Grégoire (1936) Un nouveau fragment du "Scriptor incertus de Leone Armenio", Byzantion, 11:417-427; Beshevliev, V (1936) The New Source About the Defeat of Nicephorus I in Bulgaria in 811, Sofia University Annual Reviews, 33:2 (In Bulgarian).

3. Mannases Chronicle, 1335-1340. Apostolic Library. The Vatican.

4. Michael the Syrian, Chronique de Michel le Syrien, Patriarche Jacobite d'Antioche (1166-1199), published by Jean Baptiste Chabot (in French). 1st Ed. Paris : Ernest Leroux, 1899-1910, OCLC 39485852; 2nd Ed. Bruxelles: Culture et Civilisation, 1963, OCLC 4321714

5. B. Flusin (trans.), J.-C. Cheynet (ed.), Jean Skylitzès: Empereurs de Constantinople, Ed. Lethielleux, 2004, ISBN 2-283-60459-1.

6. Joannes Zonaras. Epitome historiarum, ed. L. Dindorfii, 6 vol., Lipsiae (BT), 1858—75. Epitomae Historiarum/Chapter 24 in Epitomae Historiarum by Ioannis Zonarae.

25. Georgius Monachus. Chronicon, p.774

26. Anastasius Bibliothecarius. Chronographia tripertita, p.329

Secondary sources

7. Bozhilov, Ivan, and Gyuzelev, Vasil. 1999. History of Bulgaria. Vol. 1: History of Medieval Bulgaria 7-14 c. AD. Anubis Publishing, Sofia, ISBN 954-426-204-0. (in Bulgarian)8. Zlatarski, Vasil N. 1918 (in Bulgarian). Medieval History of the Bulgarian State, Vol I: History of the First Bulgarian Empire, Part I: Age of Hun-Bulgar Domination (679-852). Sofia: Science and Arts Publishers, 2nd Edition (Petar Petrov, Ed.), Zahari Stoyanov Publishers, 4th Edition, 2006. ISBN 9547366284.

9. Runciman, Steven (1930). A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. G. Bell & Sons, London.

10. Fine, Jr., John V.A. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472081493.

11. Bury, J.-B. (1912). A History of the Eastern Roman Empire from the fall of Irene to the accession of Basil I (802—867). Macmillan & Co., Ltd., London. ASIN B000WR1S6Q, OCLC/WorldCat 1903563.

12. Jireček, K. J. (1876) (in German). Geschichte der Bulgaren. Nachdr. d. Ausg. Prag 1876, Hildesheim, New York : Olms 1977. ISBN 3-487-06408-1.

13. István Bóna, Southern Transylvania under Bulgar Rule, Chapter II.6 In: History of Transylvania (Béla Köpeczi, Gen. Ed.), Vol. 1, 2001-2002 Social Science Monographs, Boulder, Colorado; Atlantic Research and Publications, Inc. Highland Lakes, New Jersey

14. Ivanov, Ivo (June 2007),"The Address of a Victory", Bulgarian Soldier Issue 6 (in Bulgarian)

15. Military history of Bulgaria

21. Blasius Kleiner (1761) History of Bulgaria (in Latin), translated in Bulgarian by Karol Telbizov, edited by Ivan Duychev, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Publishing House, Sofia 1977

22. Todorov Dzh.Zh., Stoyanov R.I., Ivanov I.R., and Chalakov I.H. The Lost Town: A History of Sadovo (in Bulgarian)

24. John Haldon. The Organisation and Support of an Expeditionary Force: Manpower and Logistics in the Middle Byzantine Period. In: Byzantium at War (Edited by Nicolas Oikonomides), Athens: Institute for Byzantine Studies, 1997

28. А. Васильев, Арабский синаксарь о болгарском походе императора Никифора I. В „Новый сборникъ” статей в честь проф. В. И. Ламанского, Петроград, 1905, стр. 361—362.

29. Шкорпил В. и К., Някои бележки върху археологическите и историческите изследвания в Тракия, Пловдив 1885.

30. K. Шкорпил. Материалы для болгарских древностей Абоба-Плиска. Известия Русского Археологическото Института в Константинополе, Х (1905).

31. Mărculeţ, Vasile. "Campania împăratului Nikephoros I în Bulgaria (811). Considerații asupra unor aspecte controversate." Tyragetia. Serie nouă 31.1 (2022): 293-309.

32. Warren Treadgold, The Byzantine Revival 780-842 (Stanford 1988).

33. J. Haldon, The Byzantine Wars, The History Press (Gateshead 2008).

34. D.P. Hupchick, The Bulgarian Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony. SilverLined Skulls and Blinded Armies (Palgrave, Macmillan 2017).

35. P. Niavis, The Reign of the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus I (802-811) (Edinburgh 1984).

36. R. Browning, Byzantium and Bulgaria. A Comparative Study Across the Early Medieval Frontier (London 1975).

37. Blanchard P., Guerraoui R., El Mhamdi, El M., Stainer J. Machine learning with adversaries: Byzantine tolerant gradient descent. Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA.

38. Cong Xie, Oluwasanmi Koyejo, Indranil Gupta. Generalized Byzantine-tolerant SGD. arXiv:1802.10116v3 [cs.DC] 23 Mar 2018

39. Georgios Damaskinos, El Mahdi El Mhamdi, Rachid Guerraoui, Rhicheek Patra, Mahsa Taziki. Asynchronous Byzantine Machine Learning (the case of SGD). Proceedings of the 35 th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, PMLR 80, 2018.

40. Pease, M., Shostak, R., and Lamport, L. Reaching agreement in the presence of faults. J. ACM 27, 2 (Apr. 1980), 228-234.

Footnotes

16. This is the period of the year when Sirius first becomes visible above the eastern horizon at dawn, after a period when it was hidden below the horizon or when it was just above the horizon but hidden by the brightness of the sun. The period of the heliacal rising of the Dog Star determines the Dog Days, or as the Romans called them, caniculares dies (days of the dogs). For the ancient Egyptians, Sirius appeared just before the season of the Nile's flooding, so they used the star as a "watchdog" for that event on which they based the Egyptian calendar.

17. Brady’s Clavis Calendarium, 1813

18. For the ancient Greeks, the appearance of Sirius heralded the hot and dry summer. Due to its brightness, Sirius would have been noted to twinkle more in the unsettled weather conditions of early summer. The traditional ancient timing of the Dog Days is the 40 days beginning July 3 and ending August 11; however, at present, due to the precession of the equinoxes, the heliacal rising of Sirius has shifted with 37 days towards the end of the year so that it begins on August 9 and ends on September 17.

19. The image was made with the help of the astronomy software Home Planet, release 3.3a, with Pliska coordinates 43°23′N 27°8′E. Half of the Sun's disk appears above the horizon from the east. The Dog Star (Sirius of the constellation Canis Major (Big Dog)) rises 2 minutes before the Sun (heliacal rising). The moon is late in its last quarter in the constellation Cancer (Crab).

20. Theophanes (p. 486) gives the exact day in which the expedition set out; however, the original text is damaged so that only the month is legible.

23. Distance was measured using the distance measuring tool of the free software application Google Earth, version 4.2

27. Calculated with the freeware program Home Planet, v. 3.3a, Sun/Moon info module.

Citation

This preprint can be cited as: Antonov, Lyudmil. Battle of Pliska. ResearchGate DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.13680.53767

Great! Thanks for the share!

ReplyDeleteArron

You are welcome anytime!

ReplyDeleteDear Mr Antonov; thank you for your wonderful analysis of Nicephorus' Pliska campaign. Do you know if anyone has considered the 600-700 meter ridge which lies between Preslav and Ivanovo as the site of Nicephorus' defeat in the pass? I have always thought that Varbitsa Pas was much too far from Pliska for a one day march. The wooded valley through which the modern highway 7 and the Golyama Kamchiya River run would be about the correct distance and fits the description perfectly. The ridge would be the fisrt high ground southwest of Pliska from which Krum could safely observe the Romans and gather forces. From photos the ridge does not seem a great impediment when approached from Pliska, but soon becomes steep and rugged- explaining the incaution of the Romans. Thanks again for your website! Michael

ReplyDeleteDear Michael,

DeleteThank you for your kind message which reminds me my earlier intention to update this article. It is in a sore need for update, especially in the parts concerning location of the final battle, and partly concerning the chronology.

In these parts, especially the section "Location of catastrophe", I gave the version of Vasil Zlatarski, which, although very authoritative at the time of his publication "Medieval history of the Bulgarian state" (1918), it is now hopelessly obsolete.

Whatever great sins Zlatarski has for Bulgarian historiography, this is not one of them. The fact is that at the time of his writing the main primary source for the battle was Theophanes the Confessor, and all other sources either repeated Theophanes or gave very sketchy info. About 20 years after Zlatarski, Ivan Duychev (1936) found the Anonimous Narrator (Scriptor Incertus) in the Vatican Library. Scriptor Incertus gives a very detailed account of the battle itself, including features of the battle theater which suggest that it was written by a participant or witness (Theophanes used interviews with soldiers).