Writing appears at a certain stage of human development as the most important cultural achievement of mankind. It facilitates communication between individuals and peoples; allows for the permanent storage of knowledge in mathematics, construction, medicine, history, geography, military science, astronomy, astrology; contributes to the development of literature, music and various art forms. This, in turn, creates conditions for rapid spiritual, cultural and technical progress of a society.

There are several stages in the development of alphabets – mnemonic, pictographic, ideographic. A further improvement is the phonetic alphabet with alphabets consisting only of consonants, also known as syllabic, being more primitive. The last stage of the phonetic alphabets are vowel-consonant alphabets which have signs for all sounds. They are handled more easily and are able to express abstract concepts.

A nation's possession of its own alphabet is a measure of its spiritual ascension and degree of cultural development. Since antiquity, the literate nations were given the role of spiritual leaders, of kernels for unification of humanity. It is not rare in history when people who own writing are able to survive under the most severe tests of fate, while the illiterate disappear from the historical scene after relatively mild crises.

Few ancient peoples had writing. Written records, which they left on clay tablets or papyrus, on the walls of temples or on stones, vessels, coins, etc., still arouse admiration and constant interest in historians, archaeologists, linguists. Some of these ancient peoples such as Sumerians and Phoenicians disappeared, others survived for centuries. Their descendants are rightly proud of the cultural achievements of their ancestors.

Few Bulgarians, however, know that they have had their own letters since ancient times – long before Cyril and Methodius and their students had created Glagolitic and Cyrillic. In the last decades numerous inscriptions written with the ancient alphabet have been found and continue to be found everywhere Bulgars/Bulgarians lived – in Pamir (Imeon), Bactria (Balkhara), the Caucasus, Urals, Volga region, the territory of modern Ukraine, Romania, Hungary, Serbia, Macedonia, Greece and, of course, in Bulgaria.

Not in any way belittling the work of the Solun brothers and their disciples we must admit that these genii used the millennial Bulgarian experience in this cultural field. The creation of Glagolitic and Cyrillic was an important stage in the advancement of Bulgarian culture. Glagolitic was consecrated by the Pope in Rome thanks to the diplomatic talents of kanas ubigi Boris, to the selfless work and courage of Cyril and Methodius and their disciples. Bulgarian language was legitimated as a sacred language, together with the other three languages – in which the Scriptures were to be written – Jewish, Greek and Latin. Thus, the Danubian Bulgars became the spiritual leaders of the Slavs, cultivated them and associated them to the European civilization. In order to complete the picture, we must go back in time.

Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets

| Glagolitic | # | Cyrillic | # | Sound | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⰰ | 1 | а | 1 | a | az |

| ⰱ | 2 | б | – | b | buki |

| ⰲ | 3 | в | 2 | v | vede |

| ⰳ | 4 | г | 3 | g | glagoli |

| ⰴ | 5 | д | 4 | d | dobro |

| ⰵ | 6 | е | 5 | e | yest |

| ⰶ | 7 | ж | – | ʒ | zhivete |

| ⰷ | 8 | ѕ | 6 | ʣ | dzelo |

| ⰸ | 9 | з | 7 | z | zemlya |

| ⰹ | 10 | i,ї | 10 | j | – |

| ⰻ | 20 | и | 8 | ɩ | izhe |

| ⰼ | 30 | (ћ) | – | gʲ | gjerv |

| ⰽ | 40 | к | 20 | k | kako |

| ⰾ | 50 | л | 30 | l | lyudye |

| ⰿ | 60 | м | 40 | m | myslite |

| ⱀ | 70 | н | 50 | n | nash |

| ⱁ | 80 | о | 70 | ɔ | оn |

| ⱂ | 90 | п | 80 | p | pokoi |

| ⱃ | 100 | р | 100 | r | rətsi |

| ⱄ | 200 | с | 200 | s | slovo |

| ⱅ | 300 | т | 300 | t | tvrədo |

| ⱆ | 400 | ѹ,оу | 400 | u | uk |

| ⱇ | 500 | ф | 500 | f | frət,fert |

| ⱚ | (500) | ѳ | 9 | θ | fita |

| ⱈ | 600 | х | 600 | х | her |

| ⱉ | 700 | ѿ | 800 | o | ot |

| ⱋ | 800 | щ | – | ʃt | shta |

| ⱌ | 900 | ц | 900 | ʦ | tsi |

| ⱍ | 100 | ч | 90 | ʧ | tsha,tshrəv |

| ⱎ | – | ш | – | ʃ | sha |

| ⱏ | – | ъ | – | ə,ɤ | big er |

| ⱐⰹ | – | ы,ꙑ | – | ə,ɨ | ery |

| ⱐ | – | ь | – | ʲ | small er |

| ⱑ | (800?) | ѣ | – | ê,eª | yat |

| ⱓ | – | ю | – | ju | – |

| ⱑ | – | я | – | ja | – |

| — | – | ѥ | – | je | – |

| ⱔ | – | ѧ | 900 | ę | small yus |

| ⱘ | – | ѫ | – | ą | big yus |

| ⱗ | – | ѩ | – | ję | yes |

| ⱙ | – | ѭ | – | ją | yəs |

| — | – | ѯ | 60 | ks | ksi |

| — | – | ѱ | 700 | ps | psi |

| ⱛ | – | ѵ | 400 | y | izhitsa |

The tables and text can be rendered using a font that contains both Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters such as Dilyana which can be downloaded from the AATSEEL (American Association of the Teachers in Slavic and Eastern European Languages) page.

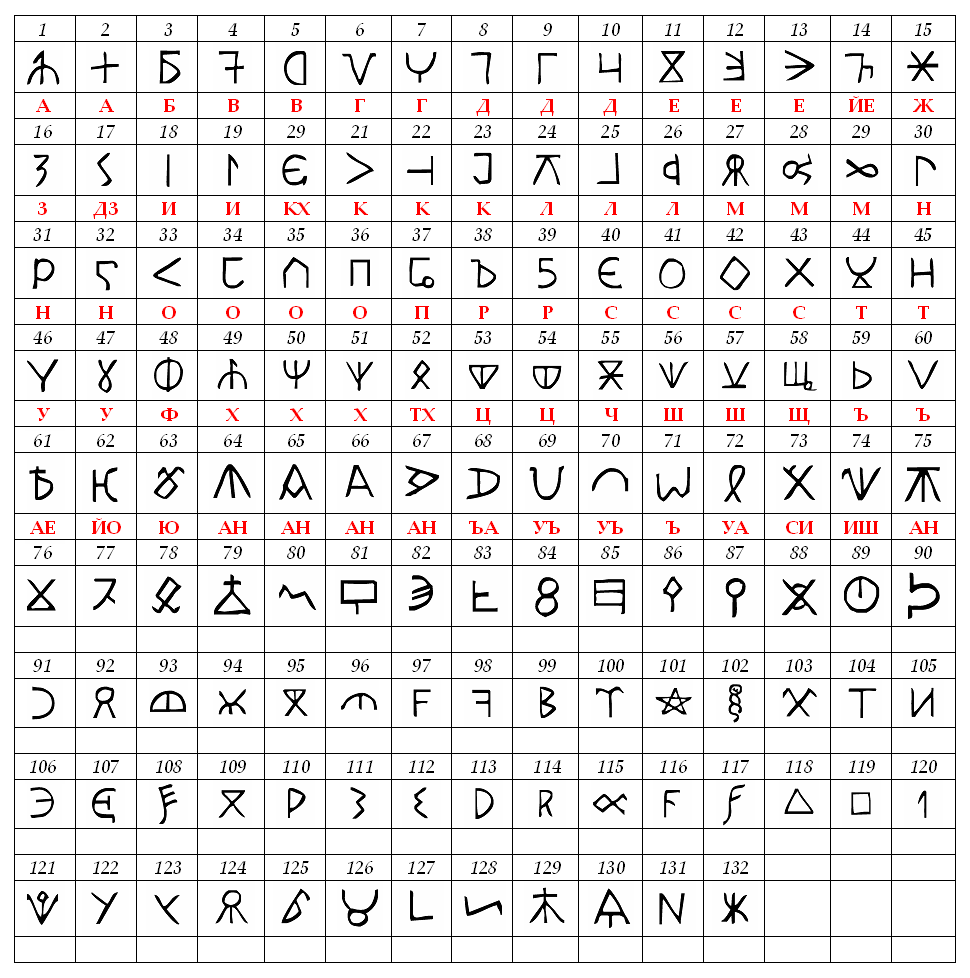

Kъnig – the old Bulgar runes

The writing kъnig emerged in the places of ancient Thraco-Bulgarian migrations in ante-deluvial times and developed in stages paralleling the other ancient writings. There have been many interactions and loanings between kъnig and these other writings.

The root of the word kъnig

(OBg: кън͡игъı) comes from the Old Chinese k'üen 'scroll' (ModCh: 纸卷 zhǐjuǎn) [57]. The word was loaned directly in the Bulgar language (*kün'ig > *küniv) restoring two individual Old Chuvash forms: 1. *k'ün'čьk > кўнчěк kind of ornament on a woman's garment

; *k'ün'-gi / *k'ün'-üg > k'ün'iv book, codex

, which is evidenced by the Hungarian könyv book

and Mordvinian konov paper

borrowings; 2. *k'ün'i- > *k'ün'i-gi > к'әn'iγь > кън͡игъı [58]. This word has been preserved in Sumerian as kunuku (inscription) and kəniga (writing, knowledge). It is inherited from Bulgar to Slavic: книга (Bulgarian and Russian), књига (Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian), kniha (Czech and Slovak), książka (Polish), and non-Slavic: könyv (Hungarian) languages.[64]

Kъnig letters (kъni) have been known from archeological finds for more than 100 years already; however, until recently, no attempt has been made to decipher them, find their phonological value, or connect them to their natural successors: the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets.

The oldest mention on the Bulgar runes is found in the mid-9th c. AD work On the Letters by the Bulgarian writer Chernorizets Hrabъr. Being already a Christian, he wrote pejoratively about the pagan Bulgars

with lines and nicks ... they [the old Bulgars] read and divined

In 1905, the Czech-Bulgarian archeologist Karel Škorpil began collecting and publishing kъni that he found on artifacts. For the next 75 years, those were neglected, for the most part deliberately.

In 1980, Lyudmila Doncheva-Petkova published a comprehensive and systematic presentation of kъni [51] which included their interpretation, as well as a catalogue with their location, aspect, the object they were written upon, and their discoverers. The Appendix contains 42 tables with a total of 1337 symbols of which 783 are defined as kъni, 14 are Glagolitic, and 185 are from the Cyrillic and Greek (Phoenician) alphabets.

In 1982, Vasil Yonchev graphically analysed the kъni, which he named tribal and unindefined symbols

. He concluded

... the bulk of these various symbols comprise, in fact, a strictly organised and logically developed system that can be reduced to a single geometric pattern [52].

In 1992, Petъr Dobrev deciphered and phonetically identified a large part of the found kъni. This enabled him to translate most of the old Bulgar inscriptions [53].

In 2000, Bono Shkodrov [54] ordered a selected set of the kъni deciphered by Dobrev into a kъnig alphabet according to their phonetic value. The kъni included in this alphabet were certain

, i.e. they were dated to the period of the First Bulgarian state before the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet (681-850 AD) and were found in proximity to the old Bulgarian cultural centers. This kъnig alphabet contains 132 letters of which 75 are phonetic and 9 are numeric.

In his study [53], Dobrev found unexpected analogy between kъnig and the writing of Ancient Elam (2700-539 BC). This was followed up by Shkodrov [54] who did a comparative analysis between kъnig and various ancient scripts found on artifacts such as sculptures, figures, pottery, architectural fragments, etc. starting from ante-deluvian times (before 5600 BC).

| Old script | # equal | # total |

|---|---|---|

| 6th to 4th millenium BC | ||

Noah's plate |

23 | 26 |

Early kъnig (Danube script+ Old European) |

200 | 272 |

| 3rd millenium BC | ||

| Sumer, Acad, and Elam | 35 | |

| Egypt | 54 | |

| Mohenjo-daro and Harappa | 19 | |

| 2nd millenium BC | ||

| Crete | 20 | |

| Biblos | 16 | |

| Hets | 19 | |

| Cyprus | 23 | |

| Bactria | 36 | |

| China | 18 | |

| 1st millenium BC | ||

| Phoenician | 10 | |

| Greek | 28 | |

| Thracian | 20 | |

| Karian | 28 | |

| Etruscan | 18 | |

| Iberian | 29 | |

| Latin | 19 | |

| 1st millenium AD | ||

| German runes | 18 | |

| Danish runes | 10 | |

| Swedish/Norse runes | 7 | |

| Anglo-Saxon runes | 11 | |

| Orkhon-Yenissey alphabet | 35 | |

| South Russia, Caucasus | 68 | |

| Danubian Bulgaria (681-850 AD) | 83 |

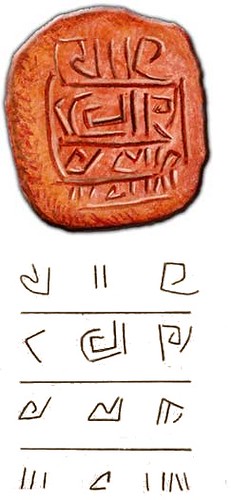

Noah's plate and Varna culture

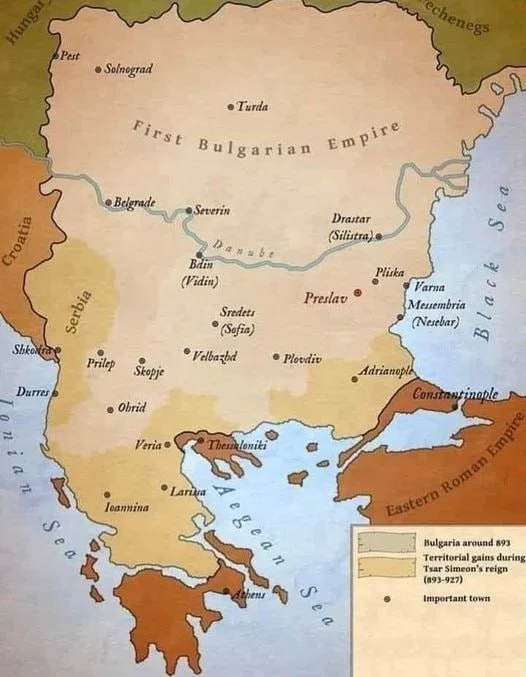

The predecessors of kъnig developed 7000-8000 years ago, some two thousand years earlier than any other known writing. The early kъni are found today on artifacts from Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, former Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, and even from the bottom of the Black Sea. These are territories which at one time or another have been included into the Bulgarian historical borders (yellow area on the map).

There is a very strong evidence that the Biblical flood (the Deluvium) happened in the Black Sea region. It is not by chance that Noah's Ark was found on top of Mount Ararat which was an island immediately after the Flood. According to the Bible, Noah was a progenitor of all modern mankind. Evidence, however, suggest that kъnig existed before the Flood (in ante-deluvial times).

Oceanological studies carried out in Black Sea in the period 1962-1998 by USA, Bulgarian, Russian, and Turkish researchers and experts found evidence about a catastrophic flood dated at about 5600 BC. This flood destroyed a highly developed civilisation that inhabited the old shores of a much smaller freshwater lake. [63] The Bulgarian participant in this expedition, Prof. Petko Dimitrov with the Oceanology Institute-Varna, found in 1985 at the sea bottom near the Bulgarian coast an artifact that he named Noah's plate

that he picked with the mechanical arm of the Argus submersible craft. This object located on the old lakeshore at a depth of 90-120 m has a shape of truncated cone with a dug-in inner part resembling a plate. On the outside of the cone and at the inside bottom there are symbols inscribed with a sharp object. Part of them are clearly visible but most are shallow traces in the plate substrate.

Noah's plate

The ideal shapes of the plate, the advanced culture of production, and mostly the statement on its pre-deluge age, disturbed even the most famous Bulgarian and foreign archaeologists who referred it sometimes as of the old Byzantine time, sometimes to the Roman period. Even more striking is the circumstance that it was made of sandstone, which testifies to the great technological abilities of the Neolithic handicrafts. Specialists refrained from giving an opinion on its age, as well as from estimation of the reliability of the facts regarding the discovery. The 1996 BBC Horizon scientific popular film Noah’s Flood that described the discoveries about the Black Sea Flood had a scene about Noah’s plate

in its original shooting. However, this scene is missing in the film. The scientific censorship entirely neglected this fact, not without the knowledge of Pitman and Ryan, the authors of [63]. They were also doubtful about the scientific reliability of facts regarding the existence of direct proofs of ancient pre-deluge culture. The attempts of Prof. Dimitrov to publish his finding of Noah’s plate

in academic editions encountered blatant ridicule. Pictures of Noah's plate published on the Web drew the attention of the well-known specialist in underwater archaeology Prof. Francesco Torre, at the Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Trapani, Italy who came to the opinion that the item looks like Neolithic ceramics (6,000-5,000 BC). Later, coming to Varna and carefully examining the plate, he confirmed his opinion about the Eneolith age of the plate. He also suggested that

The Noah’s plate is an everyday object that was used for grinding small dried beans, something as a prototype of present mortars. I suppose it was made of mud and small sand and it was baked under the Sun. I couldn’t say with certainty whether people of that time used a potter’s wheel or some primitive version of it. [62]

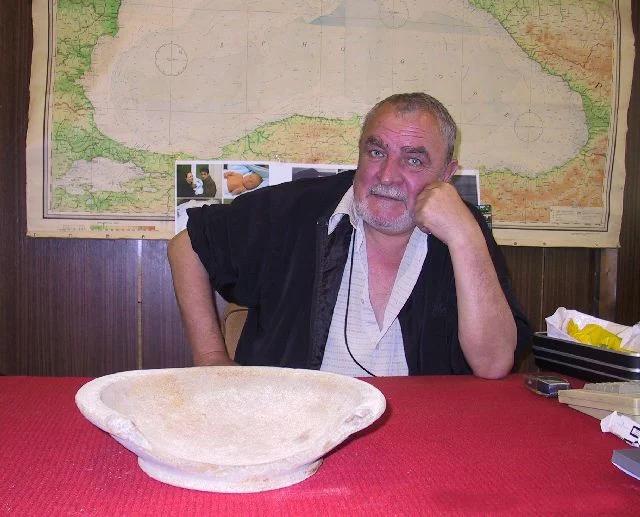

Prof. Petko Dimitrov with

the Noah's plate

The symbols carved in the outer side of the plate have a linear-geometric shape. Some of them are composites and some are repeating. The clearly visible symbols are 28 in number, of which 26 have a different shape. The total number of symbols (clear and unclear) is about 60. B. Shkodrov showed that out of the 26 legible Noah's plate symbols, 23 belong to the kъnig alphabet (kъni) [54]. This helped to reduce the number of sceptics who considered the marks as casual traces of worms and scratches, and increased the number of those ready to accept them as sign of proto-Sumerian writing. Among the latter is Prof. Harald Haarmann, the prominent specialists in ancient writing symbols, professor in multi-linguistics at the Catholic University, Brussels who considered the symbols extremely intriguing. He immediately saw parallels with early kъnig (Old European

writing as he called it) found on Karanovo seal, Gradeshnitsa plate, etc. A puzzling result that he observed in the comparison was that early kъnig has a large number of pictographic signs while the signs on Noah's plate are highly abstract. Prof. Haarmann elaborated on a hypothesis according to which there probably was a historical relation between Old European civilization and ancient Sumerian civilization. He suggested that there was a zone of circum-Pontic cultural convergence that was split into separate regions by the Great Flood, with refugees from the inundated land moving into the Balkans and into Mesopotamia. This hypothesis postulate that writing technology was among the innovations of the post-deluge age. The sign usage on “Noah’s plate” would suggest a pre-deluge script, but that is extremely difficult to prove on the basis of only one inscribed object. [62] Other hypotheses about Noah's plate

are more plausible, e.g. that it has been dropped from a ship of a later epoch.

The geological proof of the Flood convincingly testifies to an event that was extreme in magnitude with catastrophic consequences. A significant part of the land was submerged by surging waves. The old shorelines that were the center of a flourishing Pre-Flood civilization were drowned by the sea. The Bulgarian archeological museums are very proud of the remains of this civilization that have been found along the whole Black Sea coast. Indisputably, the Varna necropolis is the most important and sensational discovery of Bulgarian archaeologists.

The necropolis was discovered in 1972 during building operations in the Varna industrial zone. The interesting story of this discovery has been told by the late Ivan Ivanov who led the excavations. As well as carrying out the excavations very professionally, he made a lot of effort to have the unique Eneolithic treasure placed in the Varna Archaeological Museum.

According to Ivanov, the excavator operator Rajcho Marinov noticed an object hanging on the cogs of a litter-bin and he went to clean it. He saw other unearthed items and understood he had come upon artifacts. Marinov delivered the found items to the curator of the Dulgopol Museum, Dimitar Zlatarov, who, in turn, notified the Varna archaeologists. They were on the site on the 3rd of November 1972. The initial euphoria provoked by the discovery of the oldest processed gold coming from a civilization more ancient than Mesopotamia and Egypt, was followed by days of hard work – excavation operations, classifications, analyses, etc. An area of 7,500 m2 was explored and 294 graves with rich and various inventories were found. The great number of golden items, over 3,000 with a total weight of 6 kg, puzzled the scientists. More gold than the total amount of gold found around the world from this period was discovered in only one grave. Copper, flint, stone tools, and jewelry of metal, bones, minerals and shells of the Mediterranean mollusks Dentalium and Spondylus – about 22, 000 items - were also found. [62]

Varna Necropolis Treasure

Forty years ago, the young scientists could hardly imagine the importance of the Varna necropolis. It is irrefutable proof that an ancient civilization, older than the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, existed on the Bulgarian lands. The Varna necropolis is not the only finding of the kind. Prof. Dr. Henrieta Todorova is one of the most devoted advocates of the hypothesis that Bulgarian lands, particularly the Black Sea coast, were the center of the earliest civilization in human history. She studied the ancient history of North Eastern Bulgaria and led the archaeological excavations in the regions of Shabla, Durankulak, and Devnia. The results of her research are presented in a number of publications including The Stone-Copper Age in Bulgaria, Durankulak and New Stone Age in Bulgaria.

Here is what Prof. Todorova said in an interview under the headline The Black Sea is the earliest center of civilization in human history:

Many people are reluctant to believe that but it is true. It is obvious from the social structure in 5,000 BC which is adequate to the scientific requirements for the creation of a civilization: social differentiation of the population in rich and poor, monumental architecture, royal domination, differentiated production and trade relations. Historians discovered that these elements had first appeared on the Black Sea coast during the last quarter of the 5th millennium BC, i.e. earlier than in Mesopotamia, earlier than anything that has been known to people as the first civilization. It happened that after 1975-1976, in the opposite of the accepted concepts for early and most early, we, the Bulgarians represented something even earlier. Of course, there were reproaches that we were just telling stories. However, the excavations carried out in several very important sites offered an opportunity to trace the creation and development of this ancient civilization. [62]

This culture, called “Varna culture”, dated at 5,000-6,000 BC [62] testifies to the existence of a typical marine civilisation. On the one hand, centers of ore production and metallurgy of gold and copper were located along the coast (around the present mines of Meden Rid ('Copper Hill'), Rossen, Sъrneshko Kladenche ('Doe's Well') and Varna). On the other hand crafts flourished around large administrative centers. The constant trade relations within the Black Sea region and with the Mediterranean region were of great importance for the development of the society together with the processing of gold and copper. The Dentalium and Spondylus shells found in the Varna necropolis are most probably the oldest pre-coin forms of Eneolithic society. The old shoreline, now underwater, and the shores of the Varna lakes were probably centers of production of copper and stone tools, as well as golden jewelry. The main trade routes to the northern Black Sea and other Black Sea harbors passed through the region. This is evidenced by the 443 copper tools found in Karvuna (present Kavarna), on the Middle Dniester River bank and the finding of metal on the Volga River bank near Saratov. There are similar finds from Velke Rashkovitze in Slovakia. Analogous copper tools and golden anthropomorphous amulets are found in Varna and other places in Bulgaria. These numerous facts and findings give a sound basis for ascertaining that a significant part of the Balkan Peninsula and the Black Sea region was encompassed by identical material and intellectual cultures. [62]

Recently, a historian from Varna, well known as an intense opponent of the Flood occurring in the Black Sea, made a sensational announcement. In his book The Jews and Judaism – the beginning of the human civilization 7,000 years ago he struck public opinion with the claim that the Jews created the first human civilization. He wrote about a golden treasure dated to 4,300 BC exported from Bulgaria 30 years ago and later on ransomed by the well-known businessman Michael Chorni. Today, as the author claims, the treasure is in a bank safe in Sofia. Probably, it is a finding similar to that of the Varna Eneolithic necropolis. Of course, the pro-Jewish interpretation has been lavishly paid for. The point is that more and more new facts about the Varna pre-Flood civilization are being collected. [62]

Unfortunately, the exploration of the spiritual culture during the Eneolithic period, as well as during the other prehistoric epochs, is difficult due to lack of writing on necropolis artifacts, which would have given most of the information necessary to elucidate the basic cult-religious and everyday life characteristics of the society. Practically, all researchers are unanimous that between the Varna and Durankulak necropoles exist common features that give information about a common pre-Flood intellectual civilisation and of course, about the level of its material culture, social and economic development. [62] For the present, the Noah's plate symbols are the only writing claimed to be from a pre-Flood civilisation.

Vincha culture and early kъnig

Varna culture is part of a Balkan-wide civilisation / culture, alternatively calledDanube Civilisation(on the above map) and Vincha culture, which flourished from over 7,000 BC to about 4,000 BC when some kind of social upheaval took place: according to some, there was an invasion of new populations, whilst others have hypothesised the emergence of a new elite. This long period, spanning three millenia was, however, a time of relative stability in which a continuous archeological layer is evident in most sites, often making dating a difficult task. For this reason, many of the finds are dated either at 7,000 BC or at 4,000 BC depending on the cautiousness of the researcher in choosing either the earliest or the latest period limit. Some researchers, e.g., D. Djordjevich [65, Fig. 5] view the Vincha culture as a part of a wider world culture and extend its reaches to the whole European continent including Western Europe up to the Southern Scandinavia, the whole North African Mediterranean Coast, Middle East, and Northern Asia up to Eastern Siberia and Northern China, or, in short, all that was known as the Old World. Without negating the many ties and similarities with the other old world cultures, we are on the opinion that Vincha culture has enough distinctive features to characterise it as a distict culture centered on the Balkan Peninsula and the Southeastern part of Middle Europe.

Vincha people, close relatives of Varna culture carriers, produced golden dishes and ornaments, such as those found in the Varna and Durankulak necropoles. They created water-routes by sailing along rivers and seas, as illustrated by some pottery motifs. From a cultural, technical and social point of view, the Balkan development surpassed that of Asia Minor and, later on, Mesopotamia [55] [59]. And, more importantly, Vincha culture is characterised by a kind of pre-Sumerian writing containing so many kъni-like symbols that one cannot resist the temptation to identify this writing as an early form of kъnig.

If there had been no progress in abstract symbolism, geometry, mathematics and some form of ars scriptoria in this dynamic technical and economic scenario, it would have been practically impossible to collect, store and communicate the great amount of information on technology and mental powers as well as on the natural world and cosmos. Therefore, what remains of this early kъnig is unfathomable and tenaciously resists the efforts of anyone attempting to decipher it. Nothing is known about the existence of such a reference language. Moreover, it is too ancient for us to hope to find something like the multilingual Rosetta Stone

which would permit us to translate it into a known language. [56]

Some kъni suggest a kind of script used for blessings and invocations, for dedications, divinations, magical or liturgical formulas (not simple signs). In other words kъnig recorded language-related ideas and statements by means of standard graphic signs. It should not be confused with other communication channels used by the Balkan-people such as religious symbols, geometric decorations, figurative language, devices for memory support, star and land charts, ritualistic markings, numeric notations or simple marks stating the owner/manufacturer of an artefact. The Balkan system of communication was composed of several elements: writing was only one of them.

Many symbols are found on artifacts buried in tells (tomb mounds), popularly known in Bulgaria as Thracian tombs

. The name is not a coincidence, for the tells are found throughout Bulgaria, on territories once inhabited with Thracian tribes, as well as in parts of Southern Romania which were settled by the Thracian tribe Geti who went as far north as today Belarus where tells are found in high concentration. The Geti became known in later chronicles as Anti; together with Dacians/Venedi these were grouped with the common name Sclavini (Slavs).[61] The highest concentration of tells is in the Thracian Plain on the territory of the Odrissian Kingdom (from the Thracian tribe Odrissi). Such tells (kurgans) are found also in Anatolia and on the steppes north of the Black Sea; the latter are concentrated on the territories once inhabited by Bulgars.

Pobiti Kamъni(Upright Stones) near Varna on the right base of a column from the Sun Group and on flint tools found there. Other Mesolithic writings and pictures are found in Magurata cave, on rocks over the village of Oreshaka, Troyan Region, and elsewhere.

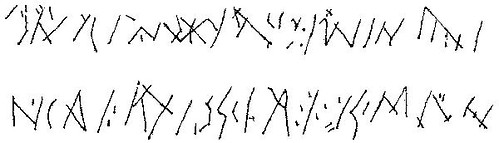

A later, Neolithic inscription was made about 6,500 years ago on the wall of a cave near Sitovo (next to Plovdiv, Bulgaria). In the cave itself, besides the inscription, Neolithic ceramics was found as well with characteristics of the Vincha group. [48] The written signs are in two lines and each row is 3,4 meters long. The signs are 40 cm. tall. One can distinguish several kъni in this inscription.

Some of the symbol-bearing artefacts found in tells are the clay idol from Taban tell near Asenovets village, Nova Zagora Region of the mid-4th millenium BC; from the remnants of the Thracian city Sevtopolis, on ceramic dishes and stone figurines in the Thracian fortresses Small Fortress

in the locality Copper Hill

near Sozopol and Paliokastro in Sakar Mountain, etc. Most kъni, 29 of them, ordered into phrases or sentences were found on 15 gold dishes from the Rogosen Treasure.

One of the oldest inscriptions, the Gradeshnitsa plaque found in a sanctuary (perhaps), recalls a ritual, shallow vase 12.5 cm long. Discovered in Vratsa (north-west Bulgaria) by the Bulgarian archeologist Bogdan Nikolov (who also discovered the Rogosen treasure) in 1969 [60], it is dated at 4800 BC and is bearing inscriptions on both sides. On the outside, it reveals an anthropomorphic stylised figure in a ritual posture with arms raised, surrounded by a great quantity of triangular and V-shaped motifs. [46]

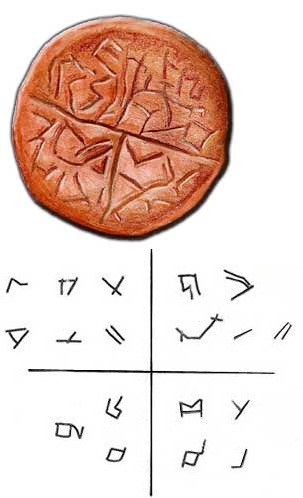

The picture shows the inside of the Gradeshnitsa plaque, bearing a long inscription divided into four horizontal segments; above each line there are three or four very different kъni crossed with religious symbols. [47]. B. Nikolov recognised a total of 24 kъni and decided that they were some unfamiliar ancient writing. There were over 100 objects with similar writing at the same age in Vratsa Museum. The ancient scribes simplified and stylised the images so that they made a transition from pictograms to more abstract forms and went beyond their original sense towards a more organised writing system. Although he was not able to decode the kъni, Nikolov thought that they had an additional meaning beside the religious one.

The best studied inscription from Bulgaria, the Karanovo stamp seal was found in Karanovo tell, in the Maritsa Valley, near the modern city of Nova Zagora (central Bulgaria). The excavation, made by Bulgarian archaeologist Georgi I. Georgiev [41], has revealed artefacts and house plans of three millennia (7th to 4th millenium BC). The tell at Karanovo has accumulated 12 meters of cultural deposits from the Neolithic to the Bronze age. This tell was formed in layers over the centuries as wattle-and-mud houses were levelled and rebuilt about once each generation.

The Karanovo seal was discovered in the remains of a house destroyed by fire; an incident which slightly scorched the seal, but ultimately has contributed to its fine state of conservation. The disk measures 6 cm in diameter, is 2 cm thick and with a handle 2 cm long.

The stamp seal is inscribed with the ancient European script and for this reason it was probably an object of prestige, placed in a prominent position and possibly used in religious ceremonies. [42] [43] The signs inscribed on the Karanovo seal are divided into four groups by the arms of a cross. The signs are straight, abstract and it is impossible to connect them to any forms belonging to the "real" world like birds, oxen, houses, etc. that are seen in later ideograms. Richard Flavin [44] [45] proposes that the incised characters from Karanovo bear a remarkable resemblance to the constellations which make up the western zodiac, in a somewhat sequential order. Such celestial ideograms could be even better precursors to the linear-geometric writing than the earth-bound

ones. This inscription is said to be 6,800 years old [43] but having in mind the context in which it was found, its age can be anywhere between 7,000 and 4,000 BC.

The most common of these early kъni has been collected and ordered in 2 inventories

: Danube script

[49] and Old European script

[50].

Danubian script and Old European combined

Signs based on "V" are the most common signs on spindle whorls, figurines and pottery. The V sign may be inverted or appear as multiple V's (chevrons). The V may also be modified by a short line placed either within the V or at the right of the V. The V is also the most frequent sign found in combination with other signs. Dating to the Upper Paleolithic, the V sign generally has a feminine reference. Gimbutas [42] associated the sign with the Bird Goddess.

The "X" sign is frequently associated with V's and is the 2nd most common sign, dating to the Upper Paleolithic. The X is especially found on pottery and is sometimes modified by a short line appended to the end of either of the two crossed lines, at the top or bottom. As with the V sign, a short line may also be placed adjacent to the right side of the X. Combinations of V with other signs include "X" (DS 37-39, 42) and a deity attribute sign (DS 45-50).

Triangles, rectangles and lozenges all appear to identify a goddess in her fertile, life-giving function; therefore, they may also be related to the pubic triangle and the V sign. The rectangle, the use of which has been compared with the Egyptian cartouche, generally contains two parallel short lines that are thought to be associated with the "goddess," perhaps as one of her defining qualities. Occasionally a short line is placed within the sign, possibly symbolizing seed or fertility. Several interesting sign clusters are composed of two or more signs - including a V sign or a whirl symbol - joined to 2, 3 or 4 lines. DS 76-81 are inscribed on ritual objects.

Two parallel lines (DS 82R; R=Ritual) that frequently have a diagonal orientation are found on numerous female figurines and may symbolize an attribute, such as the power that is associated with a deity. In particular, a goddess may be called upon to bestow a blessing or grant a wish. This is suggested by the use of two parallel lines on numerous spindle whorls as probable invocations of a goddess in rituals of magic and divination, whereas the presence of two lines together with a V sign on figurines evokes a request for reproductive fertility. Occasionally two lines are repeated, giving the appearance of a sign or symbol composed of four lines, but these examples should be understood as a pair of two lines, i.e., two and two, not four. This appears to apply to two lines in the use of script; the doubling of two lines on spindle whorls, for example, may also appear in an inscription as four lines. Reduplication intensifies an invocation as well as devotion to a deity.

Gimbutas described this force as the "The Power of Two", or the power of doubling. The Great Goddess seems to have been associated with powers that involve the number 2 and its doubles, or reduplications. Two-headed figurines may also be an expression of the Power of Two or symbolize an aspect of the Great Goddess. Two lines joined together by a bar may represent the quality of twinning. Twins are frequently considered to be special symbols of fertility, abundance or good fortune. Through time the desirable features of two lines likely tended to symbolize the goddess herself, not just her power. Then the double line would have served as a logogram indicating the presence of a deity.

Three parallel lines (DS 85R) are found on both figurines and spindle whorls and, according to Gimbutas, symbolize the Bird Goddess. However, if a bar connects the three lines, thereby joining them into one sign (DS 86R), then a triple source of power or triple aspect goddess may be indicated. A doubling of the three lines - shown either as six lines or as two groups of three lines - may reflect a ritual method of invoking the Bird Goddess. Six parallel lines appear on a number of female figurines. The common occurrence of two, three, four or six parallel lines on both figurines and spindle whorls signals their link with the goddess and calls to mind a possible use of numerology for ritual purposes. The ritual use of 2, 3, 4 or 6 lines may reflect the importance of these "lucky" numbers in a duodecimal system (based on twelve) or a sexagesimal system (based on 60).

Third millenium BC

In the period 3100-2700 BC, there were close relations between Elam, Sumer, and Acad. Most researchers think that Sumerian writing is the oldest one dating from the 3100 BC. Some are of the opinion that Sumerian influenced not only Elam but also the Egyptian and proto-Hindu (Sanskrit) writings. The oldest samples are found on the so-calledhusbandry tabletsand on seals on which the symbols had linear-geometric shapes. In the period 2700-1900 BC, the Sumerian and Elam writing transformed in abstract cuneiform shapes. This transition to cuneiform was a result of the clay-writing techniques.

The earliest phase of Egyptian writing is characterised with linear-geometric symbols on pottery. These symbols were preserved in their original shapes and used for more than 3 millenia. They were compositionally supplemented and enriched with pictograms in monumental murals. These symbols were modified in the hieratic (from the Greek meaning "sacred") or a cursive script of Egyptian hieroglyphs first used during the 1st Dynasty (2925 - 2775 BC). Hieratic script was almost always written in ink with a reed pen on papyrus. After about 660 BC, the Demotic script (demotic is from the Greek meaning "of the people" or "popular") replaced hieratic in most secular writing, but hieratic continued to be used by priests for several more centuries. I. E. Gelb noted that linear-geometric symbols on clay vessels were often found in the pre-dynastic period of Ancient Egypt [].

The Indus Valley Civilization, 2600 BC–1800 BC, was an ancient civilization thriving along the lower Indus River and the Ghaggar-Hakra river in what is now Pakistan and western India. Proto-Hindu writing is known from artifacts dug out in the cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa in Pakistan. The results of the comparative analysis with the third millenium BC writing systems is given in the Table.

II millenium BC. Unlike Egyptian writing, which developed as a mix of linear-geometric and pictorial symbols, in Crete one can clearly distinguish two separate – pictorial and linear-geometric – writings. In Hetians and Sumerians the initial phase is linear-geometric, the second phase is mixed (pictorial and linear-geometric), and the third phase is cuneiform. Cyprus has a clear linear-geometric writing. The early writing in China has predominantly linear-geometric character (inscriptions on bones used for divination). Later, the symbols assimilate cuneiform in their general visual and compositional effect. They underwent some changes in early Han period (1800 BC) when there was a partial reinstatement of linear-geometric symbols.

Many scientists have found similarities between the Bulgar kъnig, Phoenician and Sumerian writing, Chinese characters, Brahmi writing in India, Etruscan alphabet found on the territory of modern Italy, Old German and Scandinavian runes. Bulgarian researchers (Dimitar Sasselov [36], Peter Dobrev [39], Dorian Alexandrov, Vesselin Beshevliev [37] [38], etc.) pay attention to the similarity between the characters of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet and kъnig on one side and Chinese characters (mostly their old versions). Most probably, in the course of the Bulgar migrations in the general east-to-west direction, Bulgars had been picking elements of other people's alphabets whose cultures they inherited on their way.

The similarity between kъnig and the ancient Sumerian script can be explained by the fact that the creation of Sumer (Samara) involved the Bulgar Aryans. There are similar Sumerian and Bulgar words – idol (saint), kunuku (inscription), shar (to paint), zid (to erect). The same occurs in the names - Malamihr, Assen, Pərvan, Lyutskan, Gantsi, Balih, Baltin, Zvinitsas, Ivats, and others.

The similarity between kъnig and Etruscan alphabet can be explained by the fact that according to the chronicles of Volga Bulgaria, Atryach city (Troy) was established by the Bulgars whose name for the region of Asia Minor was Yana Idel (cf. Anadol, Anatolia). After the conquest and destruction of Atryach, part of the survivors led by Aeneas, sailed away and settled on the Apennine Peninsula where the natives called them by the name of their town Atryach – Etruscan.

Around 1800 BC, the Aryans from Pamir and Hindu Kush conquered northern India bringing along new culture and traditions that would play a significant role in the further development of this historic region. Vedic teachings appeared following the activities of Bulgar Brahmas in India. The Brahma Panini who was born in the capital of Balkhara – the city of Balkh, founded the first grammar of the Sanskrit language.

The Indian epic Mahabharata and the sacred books Vedi were recorded in Sanskrit with "Brahmi" writing. In Mahabharata, the name balhika/bahlika

(Bulgars) was mentioned 70 times [40]. These Indian sources, supported by some Arab chronicles (Di-mashqi, al-Biruni), write about the re-settlement in India of the ancient king Kardama, coming from Balkh, the capital of Balkhara. In India, this king founded the Kingdom of Kardamites. It is evident that Kardama came from Balkhara not only from the direct sources but also from his name, which according to Sanskrit experts, is not of an Indian origin but comes from the languages north of India, in the area of Balkhara.

Chinese chronicles refer to Balkhara with the name Bo-lo and write directly that together with the old state Bo-lo there is another state with the same name founded by Bo-lo people who re-settled in Northern India. Later chronicles write that Bo-lo (Balkhara) was settled by the displaced more eastern people Yuèzhī (月氏) whose ruler was attacked by the Huns and escaped in India where he founded a new kingdom called the Small Yuèzhī.

In the 4th c. BC in the area of Balkhara (known as Bactria in Greek literature) the meeting, mutual understanding and penetration of the Bulgar and Greek cultures took place. This happened after Alexander the Great reached here with his troops. Since then the Bulgars began to use Greek script together with kъnig. This tradition was preserved in the Kushan empire, built on the ruins of the Greco-Bactrian state that existed between 1st and 2nd c. AD.

Kъnig in Old Great Bulgaria

The early Middle Ages was a very interesting period in the history of alphabets. Various alphabets developed around Eastern Europe at that time, and some of them later spread thousands of miles by the large migrations of peoples. During this period quite different alphabets were developed almost simultaneously in the Caucasus region – the Armenian, Georgian, Caucasian Albanian, Alanian, and Kassogian alphabets, as well as the special alphabet of the inscriptions from the Humar ruins. The Seklers' writing was developed on the territory of today north Romania and later – the runic letters of the treasure from Nagy Saint Miklos. Two other writings appeared to the east at the same time: the Manihean alphabet that was characteristic of the former Sogdiana, and even further to the east – the Orkhon-Yenisey script (Turkic runes) used in areas close to China.

In this mix of writings it is not easy to determine the exact position of the inscriptions discovered in the 7-9 c. Bulgarian settlements. In the first decades of their discovery the researchers compared them mechanically with most diverse alphabets: the Orkhon-Yenisey Turkic alphabet, the Seklerian one from Hungary, the Gothic runic writing, the inscriptions from the Humar ruins, etc. The result of the comparison was that none of them could help in deciphering the inscriptions from Northeastern Bulgaria.

Northeastern Bulgaria is exactly the area once most densely populated by the Danubian Bulgars and in the 8-9th c. AD it formed the central area of the First Bulgarian Empire. Isolated kъnig inscriptions were found outside this territory – for example in the village of Shudikovo (Eastern Serbia), on the island of Pakujul lui Soare (Romania), Balshi (Albania), Varosh (FYROM), Zhitkov (Serbia), Nagy szent Miklosh (Hungary). Another alphabet appears in inscriptions to the south of the Balkan mountains: in the village of Sitovo (Plovdiv district), in the city of Parvomay and in the village Krushevo (Demir Hissar district). As this second alphabet is not attested in the earliest Bulgar centres one can assume that it was of local importance and was developed parallel to kъnig.

The finds from the village Murfatlar in Northern Dobrudja are particularly rich. About 60 inscriptions were photographed there and published – most written in kъnig and the others written in Slavic. Some inscriptions are accompanied with drawings which are particularly valuable, since they facilitate significantly the interpretation and allow relatively easy deciphering of the words, written in kъnig.

Most of the illustrative material have Christian religious content. Three of the drawings show persons in clerical garbs – most likely saints, and one – a rectangular plan, most likely a church. Another drawing depicts a bird. Prof. Edward Triarsky, who was the first to deal with these inscriptions, explained the Christian character of the drawings by the fact that they come from churches. As Murfatlar was one of the early Christian Bulgarian centres, it is not amazing that most of the drawings illustrating the inscriptions represent saints. Triarsky advanced the hypothesis that the Murfatlar script was an artificial writing created by a Greek scholar specifically for the Bulgars after their conversion to Christianity. But the occurrence of similar inscriptions in the areas of the Old Great Bulgaria points out it was a runic writing, used by the Bulgars even before their settlement on the south coast of Danube.

The reading of the runic inscriptions is particularly assisted by some Slavic inscriptions carved nearby on walls in Murfatlar, in Pliska and Preslav. Comparison of Slavic and Bulgar inscriptions allowed the deciphering of 7 of the old characters. It can be safely stated that the decoding is correct, because the Slavic inscriptions demonstrate how each of these 7 characters sounded like. But the Slavic inscriptions from the early Cyrillic centres of Bulgaria cannot help in reading the entire kъnig. Most characters from Murfatlar appear in other, older alphabets.

Particularly helpful for the interpretation of the inscriptions from Danubian Bulgaria (after 7th c. AD) is the existence of similar inscriptions from the territory of Old Great Bulgaria (2nd-7th c. AD). Acad. G. Turchaninov [33] discovered many inscriptions of this type in Southern Ukraine, in Northern Caucasus and in the Imeon (Pamir) mountains and assumed with no sufficient argumentation that they were left by the Alans and the Kassogs. But what was regarded as Alanian and Kassogian proved to be an inheritance of the Kubrat Bulgaria. In one inscription Turchaninov [33] read these two indicative words: ALANUI KAN, i.e. the "Khan of the people Alans", "the ruler of the Alans". This inscription contains the highest Bulgar title KHAN, written with kъnig-type letters. Another point of interest is that the Alans are well-known as people, once closely connected with the Bulgars. Since the 5-6th c. AD they lived together with the Bulgars in Southern Ukraine and in Caucasus. It is not a coincidence that the high ruler of the Alans bore the Bulgar title KHAN.Likewise, the similarity of the Ukrainian characters with that of Pliska and Murfatlar, the areas, in which Asparuh set foot, is not coincidental. The close political and cultural relations between Alans and Bulgars suggest the application of the already deciphered Ukrainian inscriptions as a key for those from Murfatlar. For example, it is not difficult to recognize that six out of the seven characters in the inscription ALANUI KAN are also found in Murfatlar.

Beside the Alans, the Kassogs, another people once living close to the Bulgars, had also a kъnig-like alphabet. Seventh-century Armenian sources mentioned that the people "Kash" (the Kassogs) live "between the Bulgars and the Pontus", i.e. in the area between that of Kubrat Bulgaria and the Black Sea. The Kassogs were therefore also close neighbours of the Alans. That is why there is close similarity between the Alanian inscriptions, discovered along the lower course of Don, the Kassogian inscriptions between Don and Kuban, and the Murfatlar kъnig. In one of the Kassogian inscriptions Turchaninov read the title KHAN KAISIHI, the word KHAN being written in contemporary kъnig. Seven out of the ten characters of the Kassogian inscription appear in Murfatlar, two more – of a somewhat modified appearance.

The Alanian, Kassogian and Ossetian inscriptions helped to interpret 20 Murfatlar characters. Adding another seven characters from the Slavic characters, we have almost the whole runic alphabet of Murfatlar deciphered. However, it was not clear and there was no common opinion whether the characters of these inscriptions were letters or syllables.

Frequency of character occurrence is a quantitative criterion allowing to determine the type of old writings, i.e. whether those use letters, syllables or hieroglyphs. The hieroglyphic writings consist of many characters and therefore the frequency of occurrence of an individual character is small. In the syllabic writings (e.g., Sanskrit) the number of the characters is much smaller, which increases the possibility of repetition of one and a same character in the text. Letter scripts have the highest frequency of characters.

The Murfatlar inscriptions appear to have frequency similar to those for letter scripts: each character occurs 5 times on the average (the total number of characters is 53 and a total length of the texts is 237 characters). Such frequency is untypical for the hieroglyphic and syllabic systems and shows that the Murfatlar inscriptions are written with letters.

Another problem was in which direction the texts should be read. Triarsky thought, most likely because of the wide-spread assumption that the Bulgars were Turkic people, that these inscriptions must be read from right to the left. The interpretation was based on the fact that all Turkic runic writings are read from right to the left. The thorough study of the inscriptions found on the walls of Murfatlar reveals, however, some special features:

First, the letter in the leftmost corner of one inscription is particularly large and stretched, a clear hint that the text must be read from that letter, that is from left to the right. Secondly, in almost all inscriptions the first left letters are the most carefully written ones. The further to the right we go, the more uneven and carelessly written they become. Third, in some inscriptions the last line contains only one or two characters. And these lonely characters, which obviously end the text, are either in the centre (which is likewise very interesting) or in the left corner of the line. Fourth, the lines in the longer inscriptions are aligned to the left, pointing that the line started from left.

All these special features point that the inscriptions of Murfatlar, unlike the Turkic inscriptions, were written from left to the right. This direction of writing, although rare in the East, was characteristic for a number of Iranian and Caucasian peoples – Alans, Kassogs, etc.

Further proof that the alphabet brought by the Asparuh Bulgars is not Turkic is found in the works of the well-known Turkologist R. Kazlassov, who after a thorough investigation of the two writings came to the conclusion that they are principally different. The inscriptions of Murfatlar (Besarabi) were written in a special alphabet, which does not resemble any of the well-known alphabets of the Turkic peoples. [34]

An important peculiarity, revealed by the deciphering and interpretation of the inscriptions of Murfatlar, is the quite frequent use the special church character "tilde" above some words. This character accompanies holy terms in the Christian texts, or more accurately, it is an abbreviation for holy terms.

The following words appear with "tilde":

A set of inscriptions from Caucasus renders some clarification. Inscriptions from Eastern Dagestan from the epoch of the spread of Christianity there show that some more important religious terms were denoted with special runic characters. And above these terms (although written in runes) appears the symbol "tilde". It was probably brought to the region of Caucasus by Byzantine missionaries.

The word GOD, for example, is written there as

Then, even not knowing the exact meaning, it can be safely stated that the special words such as

The stress on this symbol shows that it probably meant the common among the ancient Near East peoples word AN (GOD), which appeared first in Sumerian but later spread among many eastern peoples. It makes us believe that the Bulgars (whose homeland was situated to the east of Sumer and Accad) could have use similar religious terms in their language. The character

And finally, in this inscription below the word

The Glagolitic conundrum

The problem of the origin of the two Bulgarian alphabets is tightly connected to the problem of their age.

Josef Dobrovsky (1753-1829)

Because the Glagolitic alphabet before 1836 was known only as Croatian alphabet, an opinion held sway, based on an old Croatian legend, that this alphabet was created only for Croats; a Croatian saint, St. Jeronimus, was named as the creator. Glagolitic was mentioned in a 1248 papal letter that allowed Croats to use it in their books. In 18th c. some doubt was cast on this established belief. In 1782, the Czech scientist and founder of Slavic linguistics Josef Dobrovsky expressed opinion that Glagolitic alphabet is not very old writing but arose as late as 13th c. when Croat monks modelled it from Cyrillic for their own use.

Gelasius Dobner (1719-1790)

Soon after, in 1785, another Czech scientist, Gelasius Dobner, an older contemporary of Dobrovsky rebuffed this opinion saying that Glagolitic is an old writing, even older than Cyrillic, and that Sst. Cyril and Methodius invented the Glagolitic itself; however, very few were hesitant: Dobrovsky with his powerful authority kept most scientists on his side. He kept repeating his statement and paid little attention on the new data which other scientists collected and offered in support of Dobner's opinion. Because Dobner based his opinion, among others, on Abecenarium bulgaricum, Dobrovsky negated the antiquity of this monument putting it in 14th and even in 15th c. (Abecenarium bulgaricum is a list of Glagolitic letters and their names. The letters are written in 2 lines, and above each letter is written its Slavic name with Latin Gothic: as bócobi uédde glagoli, etc. This list was found as an inscription in a Latin manuscript of 10th c. (Paris, National Library, No. 2940); the inscription itself dates in 12th c. The Latin manuscript is now lacking from the Paris Library, but the list of Glagolitic letters is preserved in several photos). Even the discovery of such old Glagolitic monument as the Aseman or Vatican Gospel could not sway Dobrovsky and he died with the conviction that Glagolitic is not older than 13th c.

Jernej Bartol Kopitar

(1780-1844)

Only after Dobrovsky's death his opinion was rebuffed when another old Glagolitic monument, Glagolita Clotzianus, was found by the Slovene linguist Vartolomey Kopitar; by-and-by it was accepted that Glagolitic is an old writing, at least as old as Cyrillic. Kopitar wrote this, without many paleographic comparisons, in the introduction of his publication of Glagolita Clotzianus, and even suggested that Glagolitic was used by Slavs before St. Cyril. Of course, bizarre opinions kept on cropping after that, even till the present time, on the origin of this writing: some thought it as a Bogomil writing (P. Preuss, I. Sreznevsky, Palauzov) and supposed that Glagolitic was the reason for a special Church gathering in Dalmatians to anathematize this writing (Venelin, Bodyansky). The research on the Glagolitic writing kept on throwing new light on the problem: new and important Glagolitic monuments such as Zograf Gospel, Grigorovich or Mariin Gospel were found that gave rich material to Šafarik to write a review on Glagolism at that time [1] in which he described the different opinions on this issue, studied the Glagolitic letters one by one and compared them with various European and Asian alphabets, and then he gave samples of Glagolitic monuments (Bulgarian and Croatian) making printing types for Glagolitic according to the letters of the Aseman and Mariin Gospels (round Glagolitic).

Sreznevsky [2], Grigorovich [3], and Bodyansky [4] supported the antiqiuty of Glagolitic alphabet, although they maintained the then common opinion in Russia, that Stt. Cyril and Methodius first invented Cyrillic and therefore this alphabet is the original Slavic writing.

A great breakthrough in the problem of Glagolitic origin was the discovery of Prague Glagolitic Sheets, received by Šafarik from Höfler which was the basis of [5]. The Prague Sheets contain obvious traces of the Czech-Moravian language, namely, the Bulgarian sounds щ and жд are reflected in ц and з (Glagolitic ⱌ and ⰷ) which indicates that these sheets are remnants of the writing that Cyril and Methodius planted in Moravia in the 9th c. Therefore, this writing was Glagolitic, which the Holy brothers themselves should have been versed in Moravia. After the Prague Sheets became known, better understood became the place in the Moskopol live of Kliment which says that St. Kliment invented for Bulgarians more clear letters (Cyrillic).

Pavel Josef Šafarik

Šafarik [5] studied also the connection of Glagolitic with oriental alphabets, pointing that e. g. ⰰ, ⰵ, ⱓ, ⱌ, ⱍ, ⱎ, and perhaps ⰱ arose from Phoenician-Jewish-Samaritan, ⱅ – from Ethiopian (Coptic), ⰴ, ⱚ, and ⰾ he compared with the Greek δ, θ, and λ; and ⰲ – with the Latin v. About the many squiggles in the Glagolitic letters, Šafarik said that they had been taken from the Ethiopian (Coptic) alphabet.

A large number of Slavic and non-Slavic scientists after Šafarik exercised their wits with a greater or lesser success on the strange shapes of Glagolitic letters, without a final solution of this hard puzzle, left to us from great antiquity.

Franc Miklošič (1813-1891)

Franjo Rački (1828 – 1894)

After Šafarik and Miklošič, the Croatian historian and long-time chairman of the Yugoslav Academy, Fr. Rački published a study[6] in which, after the general history of writing, he dwelled on the apology of Hrabar, supposing that it concerns Glagolitic; he suggested that the prototypes of Glagolitic letters are found in the Phoenician alphabet but also mentioned an influence from Greek cursive and Albanian writing.

Rački also published the Vatican and Aseman Gospels with Glagolitic letters and wrote a study [7] on the famous Glagolitic inscription in the Croatian church St. Lucia on Krk island. This inscription is interesting because it is in the Croat redaction but is written in round Glagolitic which until then was thought to belong only to Bulgarian monuments.

At this time I. Sreznevski continued his studies on Glagolism [8] [9] in which he appended some 10 photos of known and unknown Glagolitic monuments. The same Sreznevsky acknowledged the linguistic community on the Kiev archeologic conference with the so-called Kiev Sheets, a Glagolitic monument that is as important as the Prague Sheets. After this the Kiev Sheets were published in the abstracts of the Kiev Conference in 1874 and in [10].

Izmail Sreznevsky

(1812-1880)

It is not surprising that Sreznevsky did not accept the views of the West Slavic scientists (Šafarik, Kopitar, Miklošič) about the primarity of Glagolitic. Generally, this idea did not take root in Russia. Professors like Florinsky and Sobolevsky did not believe that Glagolitic is the first Slavic writing. Sobolevsky, e. g. expressed the bizarre idea that Glagolitic was invented in Moravia and therefrom was transferred to Bulgaria!

In 1882-83, the linguistic society was acknowledged with 2 new Glagolitic monuments which the Zagreb professor Leopold Geitler found himself and transcribed in the Sinai Monastery St. Katarina – the Sinai Prayer Book and the Sinai Psalm Book. At the same time, Geitler published a study on Glagolism [11] in which he tried to prove that the Glagolitic arose from Albanian writing and even poined a place of origin: around Drin River, in the triangle Elbasan, Berat, and Ohrid.

On one hand, Geitler suggested that Glagolitic is ancient writing that arose from caligraphic modification of the Albanian alphabet but at the same time he alleged that some of its letters (ⱌ, ⱑ, ⱎ, ⱍ, ⱋ) were taken from Cyrillic writing, because according to him Glagolitic and Cyrillic were used simultaneously. This work of Geitler, otherwise full of paleogrphic comparisons, and accompanied with many photos, was reviewed in detail by Jagić [13] who debunked Geitler's idea from all aspects. Jagić wrote about it [12]:

We must give all that is due to this remarkable paleographic work; in it, the author tries to view the Glagolitic writing according to the newest approaches of paleography; however, Geitler's main idea is wrong: he does not seek the source of Glagolitic in the Greek or Latin writing but in an Albanian alphabet which it is positively known not to date from 9th c. neither its letters are more similar to Glagolitic than the Greek writing.

Vatroslav Jagić (1838-1923)

We should mention here, that after some scientists suggested a tight link between Glagolitic and Greek cursive, 2 attempts were made to back off to Šafarik's opinion that Glagolitic arose from Oriental alphabets. R. Abicht [14] suggested that Glagolitic arose from Georgian alphabet. His comparison was not very convincing, however, because, in fact, there is no similarity between the 2 alphabets; there is only some superficial likeness, i. e. at first glance Georgian alphabet resembles Glagolitic in the same way as it resembles Coptic or Armenian alphabets; however, when one compares letters one to one, he can convince himself that the similarity is coincidental – letters with different phonetic value are similar to each other.

Prof. Vondrak who held a negative opinion about this Abicht's work [15] suggested by individual comparisons that Glagolitic arose from Samaritan writing, however, this comparison was not more convincing than Abicht's; the similarity is again superficial and coincidental because it concerns letters that are pronounced differently, e. g. e and j, ъ and v, б and m, etc. But Vondrak accepted also that some Glagolitic letters were borrowed from the Greek cursive.

The distinguished Russian professor Vsevolod Müller in 1884 tried to prove the origin of Glagolitic from Sassanid writing featured in one manuscript of the Indian book Avesta. According to Müller, this writing became known to St. Cyril through the Khazars who gave it to the Russian colonists in Herson. Prof. Jagić wrote disapprovingly on the Sassanid theory [12], pp. 92-95, [13], pp. 108-113.

Simultaneously with the different opinions about the origin of Glagolitic, there was the opinion from the very start that Glagolitic has something in common with the Greek cursive writing because some Glagolitic letters closely resemble the respective letters from Greek cursive. Some scientists (Miklošič, Gardthausen, Rački, Leskien) drew attention to this fact, however, until 1881 no one had made a paleographic comparison. In 1881, the British paleograph Isaac Taylor suggested [16][17] that the Glagolitic was taken in full from the Greek handwriting such as it was used in the 9th c. He tried to establish the origin of all Glagolitic letters from the Greek cursive by comparing individual letters and letter combinations against each other through tentative transitional forms. This comparison was partly acceptable and met with an universal approval in respect to the letters that occur in the Greek alphabet but the other, typically Slavic letters from ч to the end were not expalined satisfactorily by Taylor; he made combinations that were not characteristic for the 9th c. however high one estimates the linguistic talents of the first Slavic teachers. For example, St. Cyril although he knew many languages could not arrive to the idea to write the Bulgarian sound ъ with a combination of ο and ει – therefrom ⱏ, or ц – with τσ – therefrom ⱌ, or щ – with σστ – therefrom ⱋ, etc. Even earlier in the same volume the small paper of Haferkorn was published [18] in which the Glagolitic is described as older than Cyrillic, and the 14 letters that are lacking in the Greek alphabet are explained as borrowed from Glagolitic.

Jagić [12], [13], accepting the main principle for the origin of Glagolitic from the Greek cursive writing proposed comparative tables that avoided the tortuous Taylor's combinations and gave more acceptable matches.

At the same time, a Russian paleographist, Archimandrite Amphilochius, well-known for his many paleographic works, in [19] also gave a comparative table of Greek and Slavic writing with which he showed that 18 Glagolitic letters (а, в, г, д, е, л, м, н, о, ѡ, р, с, ф, х, ч, ѕ, ѳ, and ѧ) arose directly from the respective Greek cursive letters, five were taken from Jewish alphabet (б, к, т, ш, ц), and for the rest he said that St. Cyril took them from his alphabet – from Cyrillic. Accordingly, Amphilochius supposed that both Slavic alphabets were created or composed by Cyril and Methodius, and then Cyrillic for the Orthodox Christians while Glagolitic – for the Roman Catholics!

The Russian Professor Belyaev from Kazan wrote a summary [20] of all these opinions on the origin of Glagolitic from the Greek cursive, and in 2 tables compared the Glagolitic letters against the respective Greek cursive letters together with the intermediate forms proposed by him. For most letters Belyaev agreed with Taylor and Jagić, and gave his interpretation only for some letters.

Fr. Müller [21] also deduced Glagolitic from Greek cursive and his main hypothesis was that Cyrillic letters lacking in Greek alphabet were borrowed from Glagolitic.

N. K. Grunsky, a professor in the Yurevsky (Dorpatsky) University, in his book [22] when he described mainly the Kiev and Prague Glagolitic sheets, mentioned the origin of Glagolitic and opposed Taylor's (and Jagić's) theory, i. e. did not accept that it had arisen only from Greek cursive writing but was a mixture of Greek, Latin, and Jewish letters; Grunsky did not agree with Vondrak about the Jewish alphabet origin of some letters.

Finally, let us mention a study [23] by Carl Vessely. Studying the papyruses of Archduke Reiner in Vienna, he came to the conclusion (as he said independently of Geitler) that the Glagolitic writing arose from the newer Latin handwriting. However, Vesely's comparison of Glagolitic with the Latin cursive of 2nd to 6th c. did not reveal such kinship because here, too, the similarity was not greater than the Geitler's Albanian writing.

Taking into account everything written about the age and the origin of Glagolitic, we can say that almost all West European scholars tend to describe it as older than Cyrillic and deduce it from Greek cursive while most Russian scholars have some reserves about this view with the older Russian linguists, like Florinsky and Sobolevsky denying its antiquity outright.

Older Bulgarian linguists, such as Tsonev [24] lean to the theory that Glagolitic is older than Cyrillic.

Propagation of Glagolitic

After Cyril and Methodius introduced Glagolitic together with the first religious books in Moravia, it came into wide use there until the death of Methodius in 885, after which it was replaced by Latin alphabet. However, even after Methodius' death some monasteries in Czechia and Moravia used Glagolitic for a long time afterwards. It is known, e. g., that the Benedictine Sazavian Monastery near Prague used Slavic liturgy (by Glagolitic books) as late as the end of 11th c. (1092) when Bratislav II expelled the Czech monks and put a German abbot (ecumen). The Prague and Kiev Sheets are probably written in some of these Slavic monasteries. In 1346, Charles IV himself interested in Slavic writing, founded the monastery in Vishegrad (near Prague) in which he brought Croatian monks from Dalmatia to teach the Czech brothers in Glagolitic. This monastery, known even today by Czechs as Slavic (it had also Russian monks) was then called Emmaus because it was founded just after Easter when the Gospel is read about the 2 travellers who, going to Emmaus, met the resurrected Christ (Luke, 24). Many transcriptions of Croatian books came out of Emmaus monastery; the most famous among them being the Reims Gospel as seen from a note of 1395 in its margin. The book consists of 16 sheets in Cyrillic and 31 sheets in Glagolitic containing pericopes following the Greek and Roman Catholic rites. The Reims Gospel has been used in the coronations of French kings and the strange letters that some chroniclers of this time described were, in fact, Glagolitic! Beside the transcriptions, Czech monks used the Croatian Glagolitic to write works in purely Czech language.At the end of 14th c., there were other Slavic liturgy monasteries (Glagolitic) founded by western Slavs: in Silesia (founded by Konrad II in 1380) and near Krakow in Poland (founded in 1390) [26] but nothing is known about the Glagolitic books from those monasteries.

If we follow the available data on the lives and work of Cyril and Methodius, after Czechs, Slavic liturgy and writing was accepted by Slovenians. Of course, this writing should have been at first Glagolitic but so far no Slovenian monument written in Glagolitic has been found. The only monument from the past Cyril-Methodius literary work in Slovenians – the Freisingen Prayers – was written in Latin but it likely had a Glagolitic original as its basis.

Glagolitic persisted for the longest time in Croatia – almost 1000 years. It is not known who gave Glagolitic to Croats – Slovenians or Bulgarians, but once adopted, Glagolitic writing took strong roots in Croatia, prevailed over all obstacles and persecution and passed through a long history that comes to modern times. At present, only in Croatian churches the liturgy is read from Glagolitic books, and only in Croatia Glagolitic found fierce defenders against its persecutors from Vaticana. In its many-century history, Glagolitic in Croatia not only passed through the above 3 stages but a true cursive handwriting developed which, on its side, through wide use in daily live, branched in several directions and was used until the mid-18th c. in Istria.

Glagolitic was used also in Bosnia as seen in some tomb inscriptions and in one Bogomil book (Radoslav Apocalypse) in the library of Roman propaganda. The book is from 15th c. and was written partly in Bosnian Cyrillic and partly in Glagolitic which can also be called Bosnian, because it is very different from Bulgarian and Croatian Glagolitic.

Serbia and Russia adopted Slavic writing later than the western Slavs in a time when Glagolitic came out of general use in Bulgaria. Therefore, almost no Glagolitic monuments were found either in Serbia or in Russia except a Serbian apostolic from 15th c. in which in addition to the Cyrillic text there are a few marginal notes in Glagolitic and one Glagolitic signature from the Srem Monastery Krushedol: priest David from Belgrade. [27] While the marginal notes were written with small, well-exercised handwriting, the Krushedol signature was written with large coarse Glagolitic. Both the notes and the signature were mixed with Cyrillic letters, and the notes even contain Greek letters.

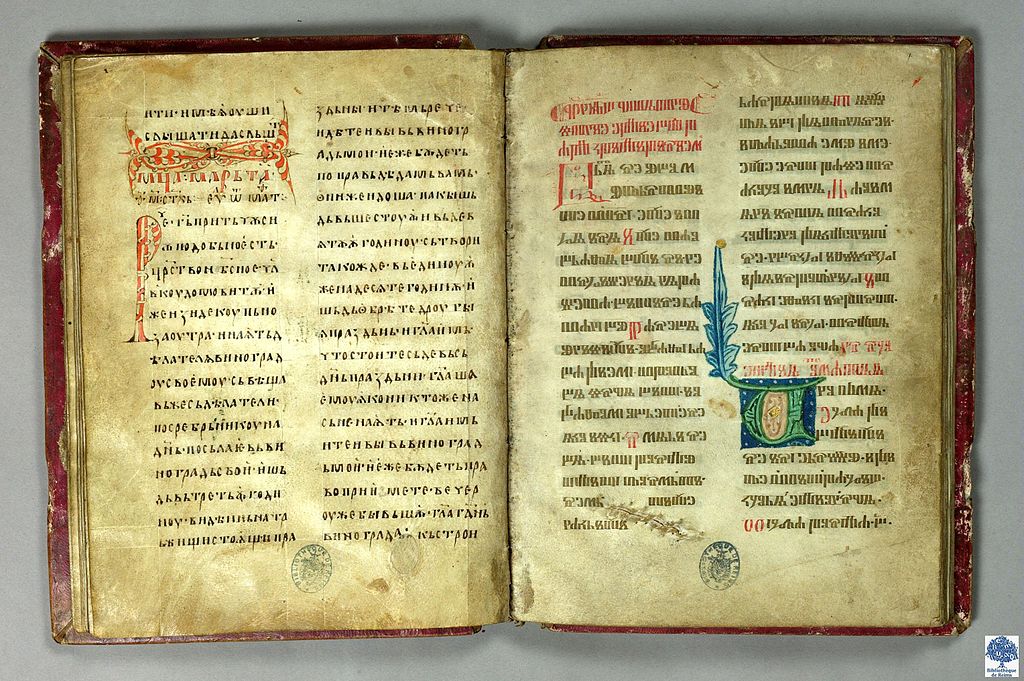

It remains to outline the development of Glagolitic in Bulgarians and when the second, Cyrillic writing developed which was used not only by Bulgarians but also by Russians and Serbs and even by Romanians until late 18th c.

If we accept that Glagolitic was established as an official writing in 855, as witnessed by Chernorizets Hrabar, i. e. before the departure of Cyril and Methodius for Moravia, then for the second writing we must look for another, later date and for another reason. An important reason for the Cyrillic alphabet appeared 9 years later when the Preslav Court accepted Christianity; therefore it is very likely that together with Christianity, eastern Bulgarians took from the Greeks the Greek Uncial (capital) alphabet for their Church books, supplementing it with letters from Glagolitic; in any case this took place during the reign of Boris, i. e. before 885 because soon after this date St. Kliment brought this alphabet to Bulgarians in Macedonia and became its propagator there. Accordingly, we can allege that Glagolitic is a West Bulgarian writing and Cyrillic is East Bulgarian; however, it is hard to delineate the areas of one or the other alphabets, or deny that even after the establishment of Cyrillic writing, East Bulgarians used Glagolitic. Prof. Jagić [28] was very specific about it and even determined borders of Glagolism stating that Glagolitic was used in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula from Struma-Seres up to Sofia-Vidin, across Danube and Panonia to Moravia. But it seems that there is no reason to limit so the Glagolism in Bulgarians; we are only certain that Glagolitic comes from Western Bulgaria (Ohrid), and Cyrillic comes from Eastern Bulgaria (Preslav) but afterwards Glagolitic was also used in the eastern Bulgarian regions with the following arguments:

- The close relationship between the 2 alphabets, namely, that the last 13 letters of Cyrillic alphabet arose from the respective Glagolitic letters, shows that the creators of the second Bulgarian alphabet used Glagolitic.

- It is very likely that together with the Glagolitic letters eastern Bulgarian literators received also the Glagolitic transcriptions from the initially translated religious books, the books that Cyril and Methodius prepared for Moravia. Because these books were written in Glagolitic, people were needed to read them and change them to Cyrillic.

- Methodius' students who found asylum in Preslav at first did not know a Slavic writing other than Glagolitic, therefore they first wrote with Glagolitic.

- There is a direct evidence that the words of the well-known Old Bulgarian literator Presbyter Konstantin were transcribed in 904 in the Patelen Monastery on the Ticha River near Preslav; if this Bulgarian literator came from Moravia, he was certainly a Glagolite.

- It is evident that Presbyter Konstantin wrote Glagolitic by his alphabet prayer in which after the letter izhe there was a verse that in the transcriptions begins with л (летитъ нъıнѣ словѣньскоѥ племѧ); this verse probably began not with летитъ but with some other word whose first letter was ћ; this letter in the Glagolitic follows just after izhe.

It follows that eastern Bulgaria shouldn't be excluded from the area of Glagolism; it is true, however, that in the eastern regions Glagolitic didn't take root as in Western Bulgaria – its original birth place; it is also true that no Glagolitic monument is found that can be said to originate in eastern Bulgaria as well as that all Cyrillic monuments with Glagolitic admixtures originate from the western Bulgarian regions.

One Bulgarian manuscript of 12-13th c. written in the region of Debar and called Bitola triode [25] contains Glagolitic writing that resembles very much Croat Glagolitic. This manuscript is otherwise Cyrillic but was probably transcribed from an older Glagolitic manuscript and because its transcriber Georgi Gramatik was versed in both alphabets, he often mixed Glagolitic letters, words even whole lines within the Cyrillic text. If we suppose that Georgi Gramatik copied a local source and did not study Croat books we must accept that in 12th or 13th c. the Glagolitic of Bulgarians in Macedonia went on its way to become elongated as in the Croat glagolashi

. Jagić [12], taking into account the angular aspect of the Glagolitic in Kiev and Prague Sheets, suggested that originally Glagolitic in Czecho-Moravia was angular while in Bulgaria it became round.

Thus, Glagolitic originated in Bulgaria where soon after the death of Cyril and Methodius it was replaced by another alphabet that we now call Cyrillic.

Advent of Cyrillic

Greek alphabet, as it was used in the 8th and 9th c. had an obvious influence on the further development of Bulgarian, and especially the Cyrillic, alphabet. On its part, the Greek alphabet was borrowed from the Phoenicians as early as 5-6th c. BC. The Phoenician alphabet likewise was not original – it was borrowed from Egypt. Of the many hundreds and thousands symbols that old Egyptians used in their writing, Phoenicians chose only 22 symbols and thus created their own alphabet in which letters designated only consonant sounds (syllabic alphabet). Greeks, borrowing these 22 symbols from the Phoenicians, adapted those to their sounds, and gave to some of them a vowel meaning, adding 2 or 3 more symbols that were needed to designate Greek sounds (phonetic alphabet). There is not only a great similarity between Greek and Phoenician alphabets but also the names of the respective letters are almost identical. Because Egyptian writing was based on images, most letters of the Phoenician alphabet still corresponded to to their names, i. e. they depicted the images of the objects whose names were taken as the names of the letters.

Phoenicians, who in their time had trade connections with the whole world, propagated their alphabet to many peoples, so that most European and Asian alphabets arose from the Phoenician alphabet. Of course, after some time the similarity between the original Phoenician alphabet and the alphabets that arose from it was obliterated so that the old connection can be established only by paleography. For example, the present Arabic alphabet which is used by all Muslims arose from the Phoenician alphabet; so does the Sanskrit alphabet, although it is apparently very different.

Some peoples, e. g. Jews and Arabs, retained the old way of writing – from right to left; others, such as Greeks and all peoples who borrowed their alphabets from them, write from left to right. There is evidence that before starting to write from left to right (about 5th c. BC), Greeks wrote both ways, i. e. writing a line from right to left, they continued the next line from left to right in the same way as one ploughs, so that the writing looked wiggly; therefore such writing was called βουστροφηδόν – 'ox turning'. As a consequence of this back-and-forth writing, the forms of some asymmetric letters were changed so that letters reverse to the Phoenician were obtained; such were the Greek Г, E, K, N vs. the Phoenician

While used by Bulgarians, Czech-Moravians, and Croats, Glagolitic developed in three stages: first was round Glagolitic which is most similar to the Greek cursive, and which has round wriggles and squiggles; then angular Glagolitic appeared in which wiggles became sharp and squiggles became triangles; and lastly, especially in Croats, came elongated Glagolitic in which squiggles became rectangles; the last type is called Croat Glagolitic because many Croat monuments were written with this writing and it was used until the end of 19th c. in some Croat regions.